ZONDERVAN

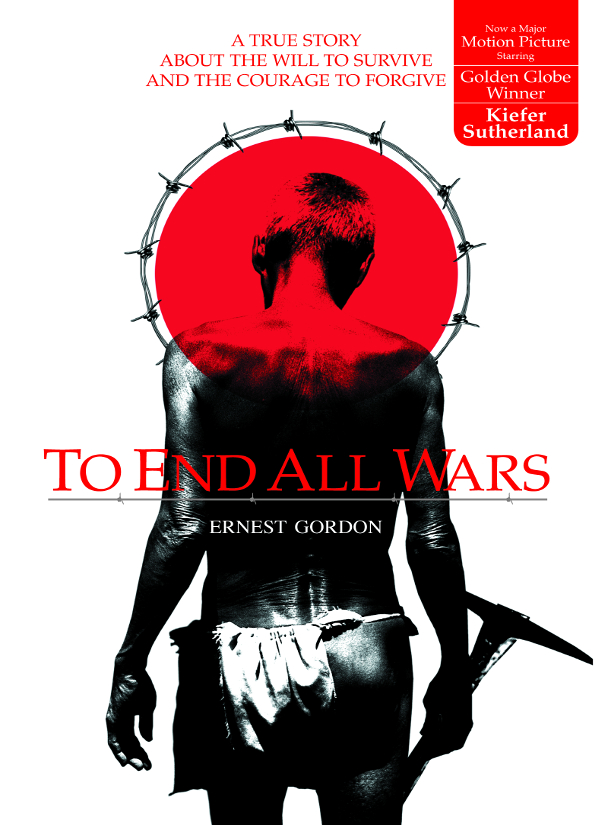

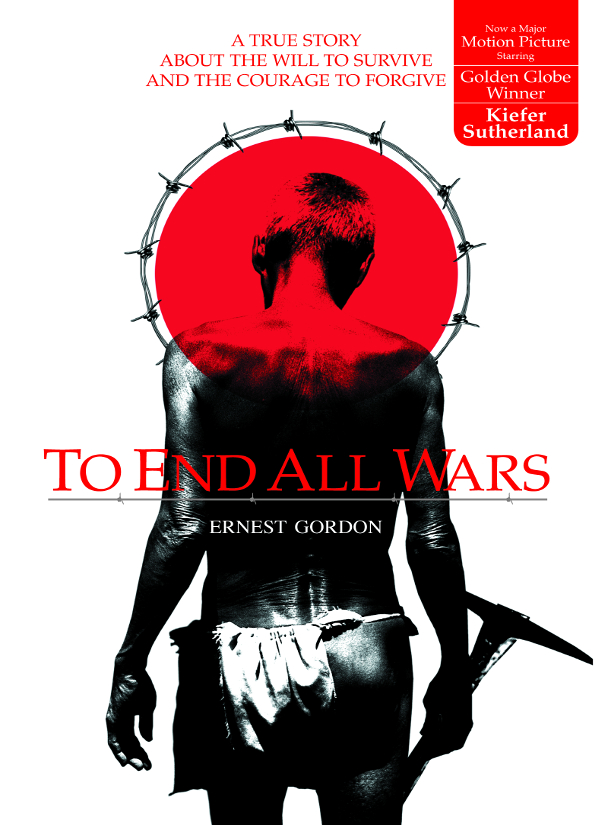

To End All Wars

Copyright 1963 Ernest Gordon

First published in Great Britain in 1963 by Wm Collins Sons & Co. under the title Through the Valley of the Kwai and in 1965 by Fontana/Fount Paperbacks under the title Miracle on the River Kwai.

First published in the United States by Zondervan in 2002.

Requests for information should be addressed to:

Zondervan, 3900 Sparks Dr. SE, Grand Rapids, Michigan 49546

Ernest Gordon asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ePub Edition February 2014: ISBN 9780310340645

All photos, except where noted, are courtesy of the Ernest Gordon Estate.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 /DCI/ 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 9 8

At the request of my children, Gillian Margaret and Alastair James, this book is dedicated to those who were my comrades in the prison camps of the Railroad of Death

CONTENTS

1 February 2000, Wampo, Thailand

I t was a pleasant morning not too hot. A brief downpour had left everything smelling sweet and fresh, and the ground was still steaming. My son Alastair and I had arrived the previous night after a flight from New York and a long drive north from Bangkok. We had come to Thailand to participate in the filming of a movie called To End all Wars, based on the story of this book. A section of the original rail line is still operational and we walked along a viaduct made of rough-hewn logs high above the river. We stopped for a rest in the cool shade of a cave and looked out over the bending Kwai Yai River. I was surprised to see how beautiful a river it was, with its steep cliffs and wild bamboo reaching into the muddy waters. The cave now serves as a local shrine and the golden statue of a Buddha sits serenely in the deepest recess.

Ironically, this area has become a popular tourist attraction. They come on package tours, take elephant rides along the river, watch native dances. Some come to lay wreaths at the war cemeteries in Chungkai and Kanchanaburi. Others come to visit a place that never really existed. They go in droves to Tamarkan and walk across the so-called Bridge on the River Kwai because they have seen the great, if inaccurate, movie by British director David Lean. Historical fact and Hollywood fiction come together in a surreal mix. Sometimes it is hard to tell them apart. Once a year, there is even a son et lumire re-enactment of the bombing of the bridge by Allied bombers in June 1945 all in a festive days outing.

There were moments on this trip when the movie version of the River Kwai seemed more tangible than the real story. It certainly felt odd to be here in a place that was still haunted by such human misery, with everything so pleasant and children selling slices of pineapple. A busload of tourists arrived in Wampo shortly after we got there. They stepped into the parking lot, took pictures of one another hanging over the ledge, bought postcards from a little souvenir hut. Some walked along the viaduct and peered into the cave where we were sitting, but they didnt stay long. As soon as a horn honked, they went scurrying back to their bus and headed off to another site.

I vaguely remembered the name of the place, Wampo, but at first I didnt recognize much about it. Then the landscape triggered a sequence of memories. There were two oddly shaped hills in the distance, almost like the stylized mountains you see in Chinese landscape paintings. I remembered the eccentric silhouettes of those hills, and then everything else fell into place. I had been here 58 years ago as a prisoner of war under the Japanese. I had lain here by the edge of the jungle; I had scrambled along this steep embankment, and waded into the muddy water where the river makes a double curve on its way south towards Kanchanaburi. I had worked with other Allied troops clearing back the jungle, helping to lay the railroad tracks that would eventually carry Japanese troops and supplies all the way to the Burma front. Today there are still a few clumps of bamboo growing here and there on the steeper hillsides, but most of the jungle has been cleared away.

Wampo was one of the first station stops on the BurmaThailand railway, the infamous Railway of Death, so called because of the tragic toll it incurred. Its 415-kilometre route passed through dense rainforest and malarial swamps, over mountains and across rivers. We were exhausted, sick from tropical diseases and starvation, overworked, injured, dying off at a preposterous rate. Sixty thousand Allied prisoners of war were forced into slave labour as well as 270,000 Asian workers. More than 80,000 died during the railways construction. Thats approximately 393 lives lost for every mile of track laid a hideous cost.

Now I recognize a spot just down the river a sandy shoal that protruded into the current. That was where our camp had been set up when we worked on the viaduct. I also remembered the cave and how four of my fellow POWs had taken refuge there during an escape, but they were rounded up by Japanese guards and dragged back to the camp. During morning roll call the men were tied to posts and executed by a firing squad. An officer fired his pistol into the backs of their heads just to make sure they were dead. I remembered the sound of the four shots. It was a sickening spectacle intended to serve as a warning: anyone attempting to escape would be executed.

A few days later we arrived at the Kanchanaburi War Cemetery in a mini-van. The movie crew were busy setting up their equipment. Production assistants were hurrying around, placing reflectors and adjusting the boom microphones. It was already hot one of the hottest days of our trip. The director, a young man in a baseball cap, was finally ready for the shot. I was told to walk through the marble arch of the entry gate and come forward at a leisurely place towards the middle of the cemetery to meet Nagase Takashi, a former Japanese officer who served as an interpreter in the camps along the BurmaThailand railroad.

I walk forward. Mr Nagase shakes my hand and makes a formal apology for the atrocities committed by his fellow Japanese. I acknowledge his apology and then we walk together to the soldiers monument at the far end of the cemetery, where we lay a wreath of flowers. We are asked to do this several times. The shot is not quite right. Mr Nagase isnt speaking loudly enough. I am standing in the wrong place. We do it again my approach, the handshake, his apology, my acknowledgement, smiles, bows, etc. repeating ourselves for the camera. It is getting hotter and the midday sun is beating down, making us all a bit queasy. Assistants run out after each shot to hold umbrellas over our heads and give us bottles of spring water.

To be sure, the moment was orchestrated, but the emotions were real. I was overcome by the sense of loss, the hatred, the senseless brutality of those years. Here in this tranquil place of manicured lawns and flowering shade trees, we walked past row after row of small headstones marking the remains of 6,982 Allied soldiers. So many brave men lost. I read some of their names out loud. There were young Scottish soldiers I had known as a captain in the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, and so many others: English, Australian, Dutch, men who would be in their eighties now, just like me. I thought of the ones who helped to lessen the suffering of others, the ones who guided me through my own time of suffering, the ones I describe in this book. My experience in the POW camps of Thailand changed my life. I survived where so many others died, but not a day has passed when I have not thought about them, my comrades, my friends, the ones who were left behind in this tropical land.

Next page