Introduction

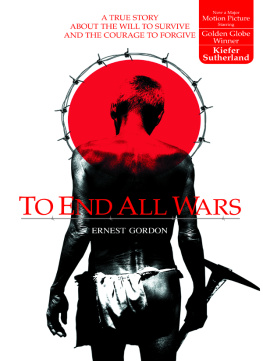

As one of the last survivors of my battalion of the Gordon Highlanders, the majority of whom were either killed or captured by the Japanese Imperial Army in Singapore, I know that I am a lucky man.

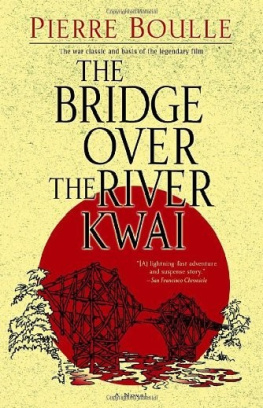

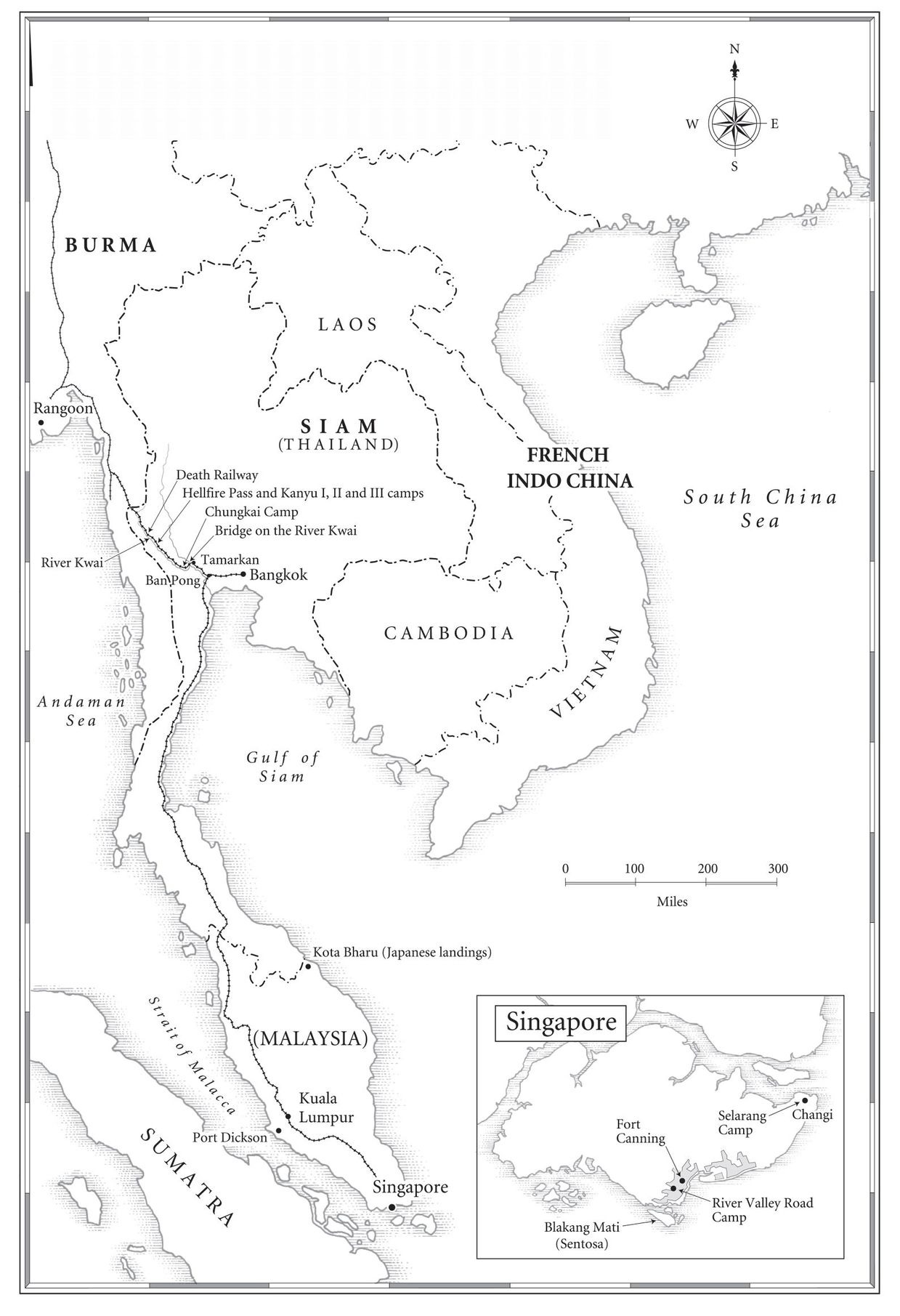

I was lucky to survive capture in Singapore and to come out of the jungle alive after 750 days as a slave on the Death Railway and the bridge over the river Kwai. Surviving my ordeal in the hellship Kachidoki Maru and, after we were torpedoed, five days adrift alone in the South China Sea, perhaps stretched my luck. So too my close shave with the atomic bomb, when I was struck by the blast of the A-bomb dropped on Nagasaki.

My story may be remarkable but for over sixty years I have remained silent about my sufferings at the hands of the Japanese. So many of us former prisoners of war did, and all for the same reasons. We did not wish to upset our wives and families, and ourselves, with unsettling tales of unimaginable torments. The memories that made us dread the nightmares which came with sleep were just too horrific. And on our liberation we all signed undertakings to the British government that we would not talk about the war crimes we witnessed or reveal what we saw in the atomic wasteland of Nagasaki.

Now I am breaking my silence to bear witness to the systematic torture and murder of tens of thousands of allied prisoners. After the death of my wife, Mary, I wrote down a personal record of everything that had happened to me as a prisoner. It was a distressing experience and at times writing this book has also been painful.

My business with Japan is unfinished, however, and will remain so until the Japanese government fully accepts its guilt and tells its people what was done in their name.

For as well as being a lucky man I am an angry man. We were a forgotten force in Singapore that vanished overnight into the jungles of Burma and Thailand to become a ghost army of starved slave labourers. During the Cold War those of us who survived became an embarrassment to the British and American governments, which turned a blind eye to Japanese war crimes in their desire to forge alliances against China and Russia.

It was our great misfortune as young soldiers to be swept into the maelstrom of the now largely forgotten Asian holocaust planned and perpetrated by Japans militarist leaders. We were not just prisoners but slaves in Japans vast South-East Asian gulag, forced to become a vital part of the Emperors war effort.

Millions of Asians died at the hands of the Japanese from 1931 to 1945. Like the allied prisoners, the British, Americans, Australians, Dutch and Canadians, they were starved and beaten, tortured and massacred in the most sadistic fashion.

Some time ago I saw a television documentary in which a Japanese railway engineer revisited Hellfire Pass, where we slaved and died on the Death Railway. He claimed that nobody had died and that prisoners had been well cared for. The prisoners and press-ganged natives who worked on the railway died in such vast numbers that to me this was equivalent to Holocaust denial. This book is my answer to those who would doubt the scale and awfulness of Japans murderous policies during the war.

Germany has atoned for the holocaust its Nazis conducted in Europe. Young Germans know of their nations dreadful crimes. But young Japanese are taught little of their nations guilt in the death of millions of Asian people, the enslavement of Korean comfort women, the Rape of Nanking, the Bataan Death March, the extermination of allied prisoners on Sandakan, the revolting human experiments conducted by the Japanese Army on prisoners in Unit 731 and the use of slave labour on the Death Railway.

Japans reluctance to admit its crimes has now become a major issue in the red-hot crucible of South-East Asian politics, and rightly so. Both China and Korea have objected to Japanese school textbooks that underplay war crimes committed by the Japanese Imperial Army.

In September 2008, at the ripe old age of eighty-nine, I travelled to San Francisco to be reunited with an old friend the USS Pampanito , which torpedoed the hellship Kachidoki Maru . I took part in a remembrance ceremony on Sunday 14 September 2008 exactly sixty-four years to the day after we were sunk in the South China Sea en route to Japan from Singapore. I stood in the control room where Lieutenant Commander Paul Summers, captain of the submarine, had tracked the Kachidoki Maru , moved in for the kill and given the order to fire. I also stood in the forward torpedo room from where five torpedoes were fired at me on that fateful night when so many poor souls lost their lives. As I watched tourists from across the world take snapshots of the grey instrument of war, I tried to make sense of it all. I could not explain why I had wanted to come to San Francisco and put myself through a lengthy flight but I had felt it needed to be done. I felt I had to lay some demons to rest, sink them to the depths like the hundreds who lost their lives in that faraway sea. It was a therapeutic process, much like writing this memoir.

Of course both mentally and physically I have never fully recovered from my experiences. In the early years after the war the nightmares became so bad that I had to sleep in a chair for fear of harming my wife as I lashed out in my sleep. My nose had been broken so often during beatings that I could not breathe through it and required surgery. The tropical diseases that racked my body gave me pain for many years and have made me a guinea pig still for the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. I have never been able to eat properly since those starvation days and the stripping of my stomach lining by amoebic dysentery. All these years later I still crave a bowl of rice. In my seventies I developed an aggressive cancer that doctors believe may have been linked to my exposure to radiation at Nagasaki. The skin cancer I am currently battling is unquestionably the result of slaving virtually naked for months on end in the tropical sun.

My time as a prisoner of the Japanese helped shape and determine my path in life just as much as my childhood did. Like it or not, the horrors did happen to me and to thousands of others. Yet some good has come out of it. My ordeal has made me a much more patient, caring person. Inspired by the devotion of our hard-pressed medics on the Death Railway I was able to care for my young daughter when she was ill and for my late wife, who required twenty-four-hour attention in the last stages of her life. While in Japan, and working with my friend Dr Mathieson, I vowed to spend the rest of my life helping others and I am pleased to say that I have done so. It is where my satisfaction comes from nowadays.