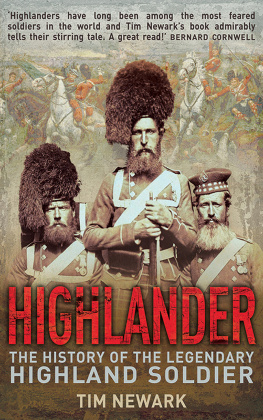

HIGHLANDER

To my father, Peter Ferguson-Newark

By the same author

The Barbarians

Celtic Warriors

Brasseys Book of Camouflage

Brasseys Book of Uniforms

War in Britain

Where They Fell

In Heroes Footsteps

Turning the Tide of War

Camouflage

The Mafia at War

Chapter 1

Making Hard Men

James Charles Stuart James VI, king of Scots was a spindly, neurotic monarch. In 1598, at the age of just thirty-two, he was convinced he was dying and wrote a book for his son, Henry, describing the state of Scotland, how it should be ruled and how he hoped the prince would follow his ambition to succeed to the English throne after the current Queen Elizabeth I. Originally written in Scots, it was called the Basilicon Doron the Kingly Gift. It was meant to be a secret book, published in a very limited edition of seven copies, but news of its controversial contents leaked out.

Once the Scottish king became James I of England in 1603, a second, revised edition was widely published to great interest in England. In the original, uncensored copy of the book, James revealed his true Stuart arrogance and expressed especially his disdain for one group of his subjects the Highlanders.

As for the Highlands, I shortly comprehend them all in two sorts of people: the one, that dwelleth in our main land that are barbarous, and yet mixed with some show of civility: the other, that dwelleth in the Isles and are utterly barbarous, without any sort or show of civility.

King James recommended they be treated as wolves and wild boars and that his son establish colonies among them of answerable inland subjects, that within short time may root them out and plant civility in their rooms. Yet, it was to these same Highland wolves that the Stuart dynasty would later turn to help them back into power after they were deposed at the end of the seventeenth century.

It was true, the Highlanders were not as sophisticated as the elegant Frenchified courtiers who thronged around James in Edinburgh, but this was hardly surprising. These were men and women surviving in a harsh environment, rain- and wind-swept, with the poorest soil in the British Isles. Once a family was fed, there was little left over for the fineries of civil life. In dress, in the manner of their outward life, and in good morals, wrote a sixteenth-century chronicler, these come behind the householding Scots yet they are not less, but rather much more, prompt to fight...

The Highlands of Scotland are hard in many ways. The rock that makes the landscape so dramatic is a barrier to drainage. When rain runs off the mountain tops it collects in valleys where there is no escape for it into subterranean chambers. Rain and snow are frequent, brought by Atlantic clouds, and moisture lingers on the surface to make the land marshy and sodden. If you make the mistake of stepping off the main road into this terrain, you quickly find yourself sinking into boggy ground that drenches your boots and makes walking tough work. A modern tarmac road is like a bridge across this water-soaked landscape.

For much of its early history, the north of Scotland was a virtual island, cut off from the rest of Britain by the Firth of Forth in the east and the Firth of Clyde in the west and the boggy land that spread out from around the heads of these inlets. The only place to pass though this moss was at Stirling, which made the city crucial to controlling the north. Only a few miles to the south, Robert Bruce made good use of the wetland, forcing invading English knights and archers to stagger and drown in the marsh around Bannockburn in 1314.

At this famous victory for the Scots, the Bruce numbered some Wild Scots among his troops who rushed upon the enemy in their fury as wild boars will do. They fought with daggers, spears and long-handled Lochaber axes, and when they came to close combat they did not hesitate to throw off their tartan clothes and offer their naked bellies to the point of the spear. It was an early demonstration of Highland battlefield rage.

For centuries, beyond this boggy barrier around Stirling, the north of Scotland evolved detached from the rest of Britain. It was a much more significant geographical frontier than the conventional Highland line, which follows a north-easterly geological fault line from the Clyde to just south of Aberdeen. It was only in the late eighteenth century that the marshy land around Stirling was drained, opening up the Highlands to modern roads and then railways. Until then, the more efficient method of transport was by sea. Highland merchants passed along the west coast and criss-crossed the Scottish islands of the Hebrides, Orkneys and Shetland, creating a trading network that stretched to Scandinavia.

The damp valleys and craggy mountains only allowed for the poorest kind of agriculture the grazing of small herds of hardy cattle and sheep, with little profit to be made by the farmer. Large communities could not be sustained by this kind of living. Only the great estate owners the clan chiefs had any wealth, but this was paltry compared to southerners.

The food and drink available to the poor Highlander was meagre. Cattle were raised to be sold, so little meat was eaten, leaving only oats, barley, cabbage, potatoes, turnips and cows milk to form the staple diet. Oat cakes and cheese might be a typical meal, with a winter breakfast, known as tartan purrie, being a porridge of oatmeal and the juice of boiled cabbage. Treats would be wild fruit or game, or fish and seafood if you lived near the coast.

Alcohol featured significantly in the lives of the richer classes and hard drinking was expected. A Highland hierarchy of booze was described as claret and brandy for the lords and lairds, port or whisky punch for the tacksmen (tenant farmers) and estate managers, and strong beer for common husbandmen. In the Memoirs of the Life of Duncan Forbes of Culloden, Forbess biographer made clear his disapproval of this excessive drinking.

Tis a custom in the North of Scotland (highly indeed to be despised and abhorred) among the generality of gentlemen, to think that they do not entertain a visitor in a proper manner, unless they actually shall make him drunk: and indeed so far has the delusion spread that the visitor scarce judges himself well used, if he be left pass without the usual compliment...

Although Forbes was a Lowlander, his estate was in the Highlands and he was happy to join in the customs of his clan chief neighbours, so that he and his elder brother won the reputation of being the greatest bouzers, ie the most plentiful drinkers in the North.

An Englishman travelling in Scotland in the 1720s heard of a drinking contest in which English officers unwisely challenged some Highland gentlemen. The Highlanders won, well practised in drinking quarts of whisky, while the Englishmen suffered badly. One of the officers was thrown into a fit of the gout without hopes, it was recorded, another had a most dangerous fever, a third lost his skin and hair by the surfeit.

The geographical isolation of many Highland settlements meant they had to look after themselves. Young men were forced into the role of protectors, hunters or bandits, and it was customary to carry a weapon and maintain a fierce pride. Personal insults were settled by violence and injustices against a community by armed retaliation, raids and counter-raids. Highland songs and poetry demanded their young men be as fierce as wild cats.

O children of Conn of the Hundred Battles

Now is the time for you to win recognition

O raging whelps

O sturdy bears

O most sprightly lions

O battle-loving warriors