First published in Great Britain in 1990 by

Michael Russell (Publishing) Ltd

Reprinted in this format in 2016 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Lady Fraser, 1990, 2016

ISBN 978 1 47382 733 2

eISBN 978 1 47388 435 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47388 434 2

The right of The Hon William Fraser to be identified as Author of this work and David Fraser to be identified as Editor has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

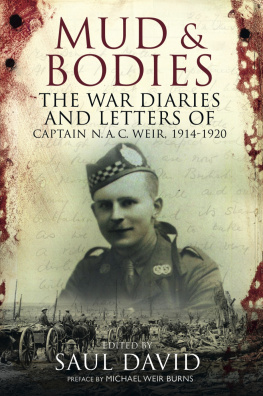

Preface

My fathers letters and diaries, from which extracts are given in the following pages, concern the First World War on the Western Front. He served there consistently throughout except when wounded or injured (and excepting some months commanding a Corps School in France), and he served both at regimental duty, including battalion command, and on the front line staff. The war dominated his youth he was a subaltern of twenty-four when it began, a lieutenant-colonel of twenty-eight when it ended; perhaps dominated his life.

The views and experiences related here echo a great deal already written about that war the devastating strictures on much of the High Command and staff, the anger with incompetence and amateurishness, the pain of bereavement, the misery of physical conditions there is little startlingly new. My fathers record of the times may, nevertheless, be of some interest beyond his family. History is not only concerned with accurate chronology and analysis. It also attempts or should to convey that often most difficult of impressions: what it was like to be there. In this, perhaps, these spontaneous and youthful writings of long ago contribute something.

It is a something particularly poignant to one of my own generation, born immediately after that struggle of 191418 and with childhood much affected by talk of it; yet subsequently living through later wars and other dramas whose impact and myth were so different as to make The Great War as we grew up calling it far more remote in spirit than its comparatively short distance from us in time might imply. It was a war which ended an era; which was conducted largely free of what would later be called ideology; which in the case of the British Army (although not their enemy) made, on the whole, far heavier demands than subsequently on human endurance, for the four long years in which the Army faced the main weight of German power. It was a war which involved unprecedented loss and suffering, and yet there is something else too, which may be found curious and paradoxical by some, yet rings with a familiar note in my own ears. I often wonder, my father wrote in his diary on 14 August 1918, how many, even of those who have suffered most, could they put back the hand of time four years and arrange it that there should be no war, would do so? Not I, certainly I think I have seen more real happiness here in France during the agony of these days than ever I saw before. Such must be set against the grief, and the frequent yearnings for the wars end.

It was a war in which simple patriotism was, for most of the time, an unquestioned faith; and in which consciousness of the rightness of that patriotism inspired both sides to a remarkable degree and for remarkably long. It was a war from which the British Army tiny and professional in the beginning, huge and representative in the end emerged believing that it and almost it alone had won the day. It was a war, as Corelli Barnett observes in his preface to The Swordbearers , as near as ones fathers youth and yet as remote as the Crusades; lances of the Garde Ulanen scratching the summer sky of 1914; guns of Jellicoes thirty-four capital ships firing the valedictory salute to British sea-power into the mists of Jutland: horizon blue and field grey; the Motherland, the Fatherland, La Patrie .

My father kept a diary at the beginning and in 1915 although the latter has not survived. He kept one again, continuously, from January 1917 until after the Armistice. He never took his diary into the trenches but wrote it up after a spell in the line; and he was, whether in or out of the trenches, a regular letter-writer, so that much appears in both letters and diaries which has required editing to reduce repetition. Here and there, particularly in the 1914 Diary, I have needed to insert some dates by guesswork and research in order to help the sequence, since these were often omitted. Place names, also omitted at the time in the interests of somewhat patchy security, were generally inserted by him later.

My father was a dedicated and thoughtful professional soldier and the overall picture contains much criticism particularly of lack of forethought and competence in higher staffs and much lamentation over lack of system in training. My father believed, with passion, that reinforcements were sent to France and Flanders with inadequate initial training: that officers and NCOs never received the sort of systematic traning for their responsibilities which he thought should be essential prerequisites for promotion; and that battalions, in their turn, were given insufficient time and resources for training between battles or spells in the line. He took the view that tactical doctrine and knowledge of how to train men intelligently were deplorably ignored in the British Army. He was convinced that training, at every level, would have drastically reduced the casualty lists; for although he sadly recognised that the conditions of the Western Front meant that battles inevitably involved much loss he nevertheless attributed a great deal of that loss to inexperienced leadership and faulty basic training.

But of the underlying strategy my father had no doubts any more than he had doubts of the fundamental justice of the cause. He was totally convinced that the war had to be fought and won on the Western Front; and that this involved attrition on a huge scale, and Allied offensives at the right time and place, under the right conditions for he could not challenge the underlying political reality that the German Army was occupying much of northern France and most of Belgium and had to be dislodged. He quarrelled not with the strategy but with the tactics, or some of them the dream of breakthrough, where he favoured the limited attack succeeded by others of the same sort elsewhere. His criticisms were, of course, those of a young man, often exaggerated and perhaps unfair like many such; but he saw a lot of the game, and although he was genuinely indifferent to honours, his Military Cross, his three awards of the Distinguished Service Order, as well as his three Mentions in Despatches (the fourth, referred to in the text, was in 1940) indicate that he knew that game pretty well.