First published in Great Britain in 2016 by Osprey Publishing,

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK

1385 Broadway, 5th Floor, New York, NY 10018, USA

E-mail:

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

OSPREY PUBLISHING, PART OF BLOOMSBURY PUBLISHING PLC 2016 Osprey Publishing Ltd.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publisher to secure the appropriate permissions for material reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Tim Newark has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this Work.

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2000-6

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2001-3 (ePDF)

ISBN: 978-1-4728-2002-0 (eBook)

All images are from The Kobal Collection

Osprey Publishing supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations will be spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

www.ospreypublishing.com

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.ospreypublishing.com. Here you will find our full range of publications, as well as exclusive online content, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters. You can also sign up for Osprey membership, which entitles you to a discount on purchases made through the Osprey site and access to our extensive online image archive.

INTRODUCTION

In past centuries, great battles and the sacrifice of soldiers were often commemorated by large statues erected in capital cities. The Parthenon frieze on the Acropolis in Athens portrays the ancient Greek warriors who defeated the Persians and kept their civilisation free. In the heart of London, the statue of Nelson raised high on a column celebrates his victory at the battle of Trafalgar over Napoleon the man who wanted to conquer all of Europe. Today, alongside days of remembrance and the erection of new memorials, we most frequently and widely commemorate our battles and soldiers through war movies.

Ever since the beginning of the 20th century, filmed dramas have been the major way we understand and appreciate past conflicts. As befits a free society, these films are often critical of the conduct of past battles and question the value of so much loss, but they also present the individual courage, camaraderie and professionalism of soldiers. From the very first war documentary depicting the battle of the Somme, to perennial film favourites, such as Battle of Britain and The Longest Day, they remain the most popular art form that reminds us of the duty and sacrifice of our armed forces. These are the war memorials of today.

Tim Newark, 2016

Film number:

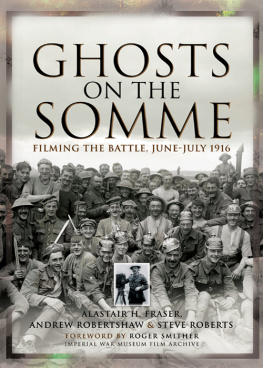

THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME

Date: 1916

Duration: 74 min

Director:

Geoffrey H Malins

A documentary about combat on the Western Front in World War I, The Battle of the Somme was released as a feature film and proved enormously popular, attracting some 20 million cinemagoers in its first six weeks. It is often called a propaganda film, but it does little to glamorise the fighting and shows the dead and wounded on both sides in a remarkably humane depiction of the war.

The film begins with preparations for the great Allied offensive on the Somme in June 1916; we are shown the vast number of horses needed to transport armies and striking images of massive piles of shell cases. We see the ferocious artillery onslaught on the German positions, including plum pudding bombs for smashing barbed wire. The cinematographers know that the audience made up of many parents and families of the serving soldiers are as interested in the everyday lives of their men on the front line as the fighting, and they show the soldiers having dinner in camp the night before the attack, cooking food in a big pot, and fixing wire cutters on to their rifles.

The battle itself begins with the iconic image of a massive mine ignited on Hawthorn Ridge, sending up a great plume of earth. We then see soldiers going over the top from their trench, but this scene was a later recreation shot behind the lines and is one of the few false moments in the documentary. It does, however, have a feature film sensibility as we then see these soldiers disappear into the mist of no mans land. Harsh reality is provided by scenes of a wounded soldier being carried back to his trench, who we are told then died shortly after filming. Towards the end of the film, we are shown the dead and wounded of both sides. We see streams of German prisoners of war, shell shattered trenches, and a dead dog that went in with his master during the attack. The bizarre landscape created by war is depicted by men scrambling up the sides of a 40-foot-deep shell crater.

The film ends on a positive note with cheery soldiers waving to folks at home and a map showing 12 miles of captured territory. But the undeniable reality of the film must have been shocking for some on the home-front and undoubtedly contributed to its popularity it was shown in numerous cinemas in the UK and abroad for months afterwards as it expressed so much more than newspaper reports could. The Battle of the Somme can truly be seen as the first great war film.

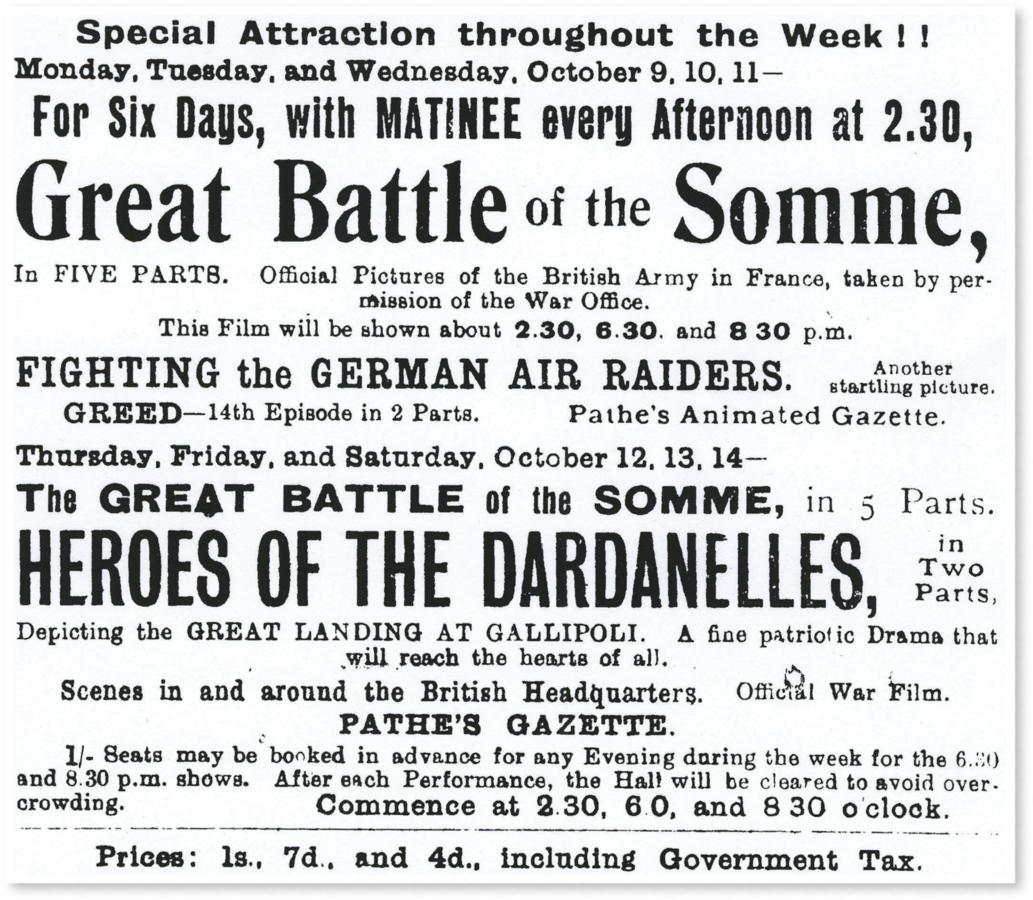

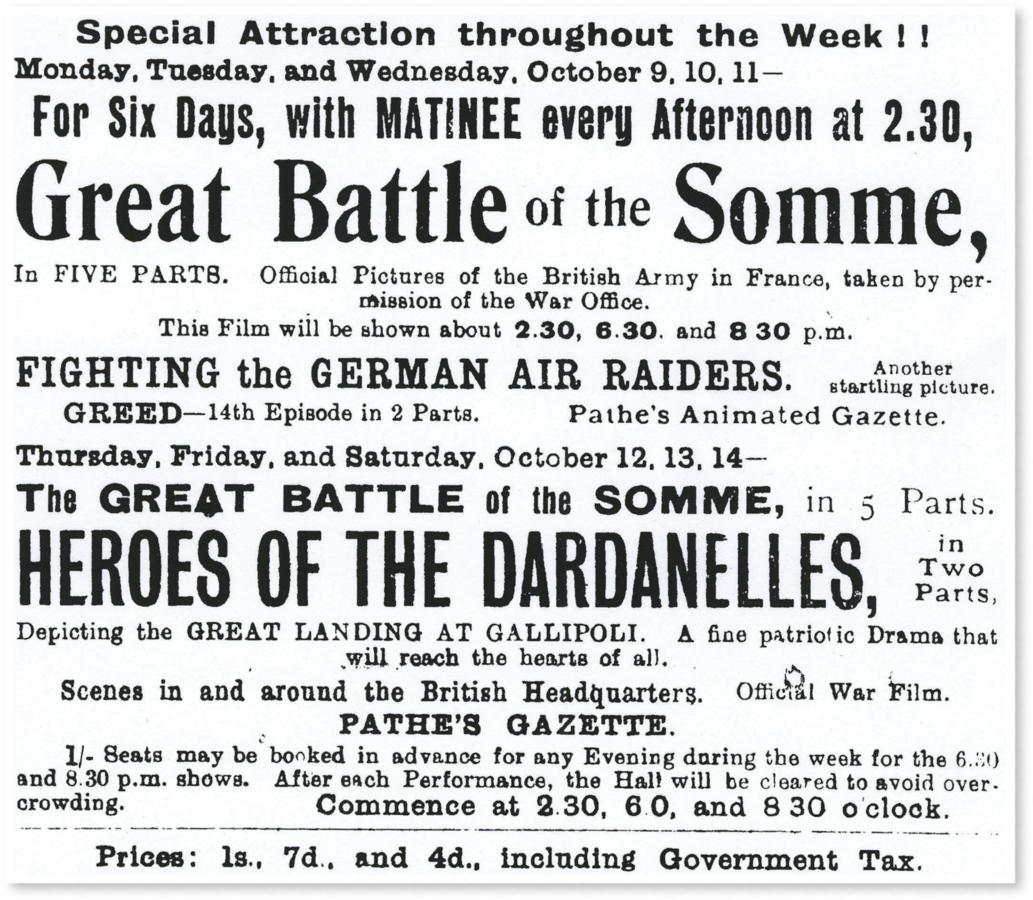

A poster for The Battle of the Somme. The film was a great success, both in the UK and abroad, being shown in numerous cinemas for months after its initial release.

This scene, showing British troops advancing into no mans land, was actually filmed at the British Third Army mortar school near St Pol, France, and was one of the few staged for the film.

The destructive power of modern artillery was revealed to audiences in this scene of intense barrages prior to the Somme Offensive.

Film number:

ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT

Date: 1930

Duration: 152 min

Director:

Lewis Milestone

Writer:

George Abbott

Academy Awards:

For best director, production and best picture

An outstanding epic set on the Western Front in World War I, this is the first great talkie war film. Based on the best-selling German novel of the same name by Erich Maria Remarque, it expresses a post-war reaction to the conflict, portraying the ordinary soldiers of both sides as the victims of incompetent and misguided commanders. It set the tone for many more such anti-war movies later in the century.