To my father, who took me to see Gone With the Wind in 1967.

To my mother, who let me read her copy of Gone With the Wind in 1969.

To Ron Haver, who ran David O. Selznicks print of Gone With the Wind for me in 1975.

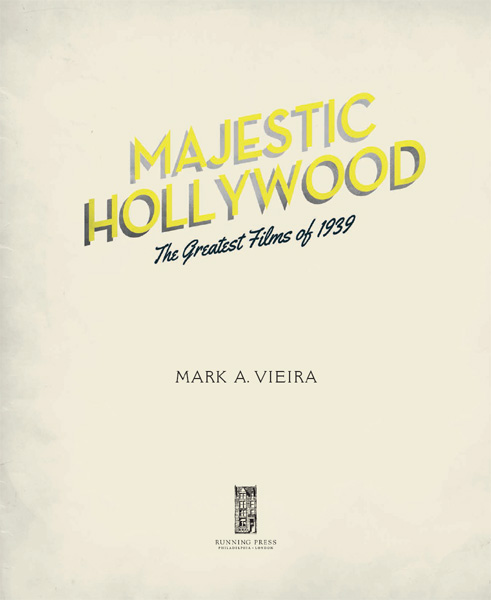

2013 by Mark A. Vieira

Published by Running Press,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved under the Pan-American and International Copyright Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher.

Books published by Running Press are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013945945

E-book ISBN 978-0-7624-5164-7

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

Cover design by Dan Cantada

Interior design by Susan Van Horn

Edited by Cindy De La Hoz

Typography: Neutra text, Yellowtail, and MeyerTwo

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

CONTENTS

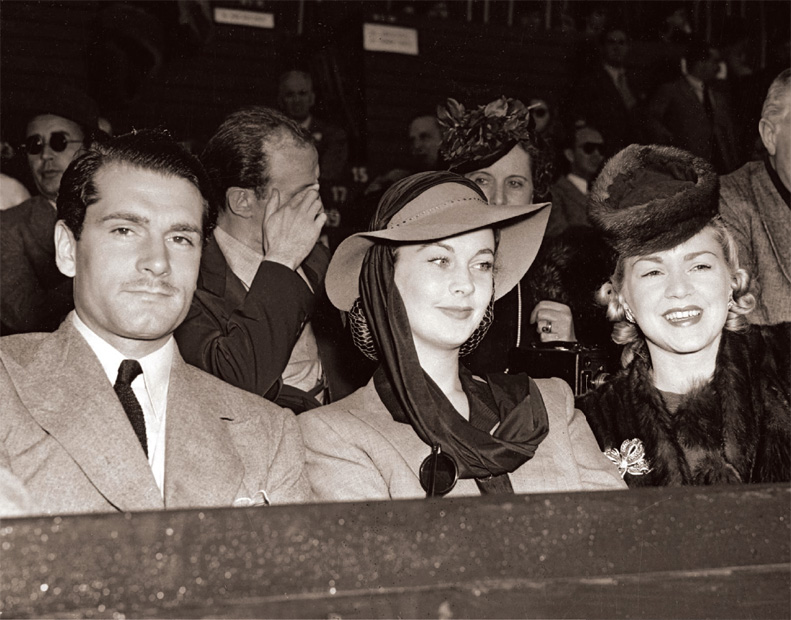

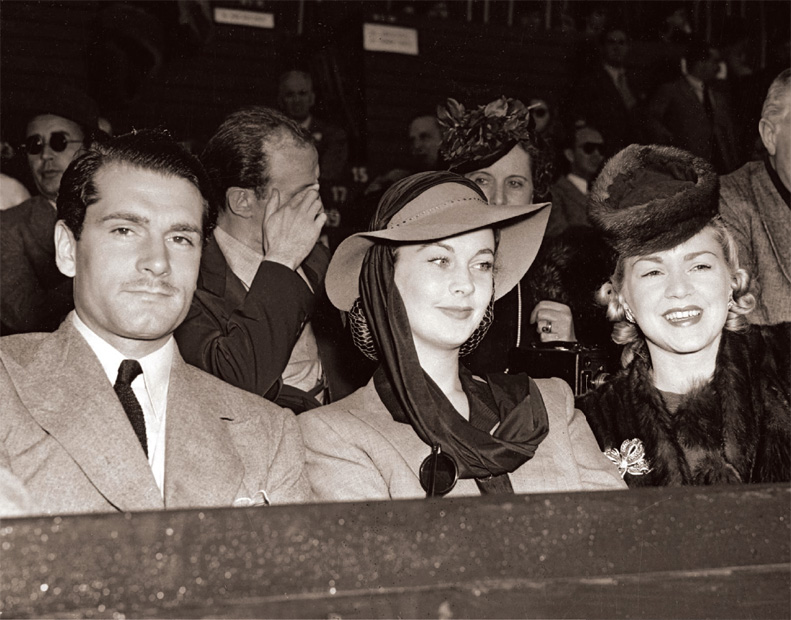

Three stars of prominent 1939 films were caught in a candid racetrack photo: (l. to r.) Laurence Olivier (Wuthering Heights); Vivien Leigh (Gone With the Wind); and Claire Trevor (Stagecoach)

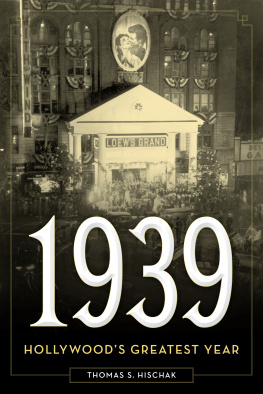

N ineteen thirty-nine was a watershed year. The Great Depression was barely over, but America was again feeling the chill winds of change. Politics, economics, and art braced for war. There was a lull before the storm, and Hollywood, as if expecting to be judged by posterity, produced a portfolio of classics. What year before or since has yielded as many masterpieces? How many calendars have glistened with releases like Gunga Din, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Only Angels Have Wings, Destry Rides Again, Beau Geste, Son of Frankenstein, The Women, Drums Along the Mohawk, Union Pacific, The Wizard of Oz, Stagecoach, Ninotchka, Of Mice and Men, and, of course, Gone With the Wind? In 1939, every week was a cinematic cornucopia. This volume showcases fifty classics from that majestic year.

We are fortunate that these films, and the photos that heralded their releases, have survived the decades. These films were magical experiences. Their production created equally magical images. Whether scene stills, behind-the-scenes shots, or portrait art, these images are as enchanting and powerful as the films they were meant to publicize. The histories of these films include anecdotes from the artists who made them: directors William Wellman and John Ford; cinematographers Arthur Miller and Lee Garmes; actors Judy Garland, Henry Fonda, and Olivia de Havilland. Their stories are here, transporting the reader to an era when Hollywood trusted the intelligence of its audience and presented insightful, sensitive films like Wuthering Heights, Goodbye Mr. Chips, and Midnight.

In 1989, a number of commercial and critical entities decided that 1939 was special; after all, it had yielded two perennial moneymakers, The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind. The litany of other titles was sufficient to convince any skeptic, so no one asked what caused this outpouring of excellence.

If one looks at Hollywood in 1938, certain clues emerge. America was a short five years removed from the Great Depression. There had been a mini-boom in 1936, which was followed by a slight slump in 1937. Box office improved markedly in 1938, which in itself would allow for bigger and better films, but there were other factors. Labor disputes which took place between writers and producers in 1936 had been settled; screenwriters were better treated and paid. Studios could afford to cultivate staff writers and attract celebrity authors of hit plays and bestselling novels. Big prices were paid for big properties.

In July 1938 the Justice Departments antitrust division filed a lawsuit against Hollywoods eight major studios. Owners of independent theaters claimed that the studios block booking was denying them first-run films. United States v. Paramount Pictures et al. said that the eight major studios were violating the Sherman Antitrust Act by forcing these independent theaters to take blocks of inferior films. It was only a matter of time before the five major majors (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, Paramount, Twentieth Century-Fox, Warner Bros., and RKO Radio) would be stripped of their monopolistic imperatives, so they began thinking in terms of bigger productions, which they need not offer to independent exhibitors. Making B pictures could be left to the major minors (United Artists, Universal, and Columbia) and independent producers.

Seeking to boost morale, the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) launched a campaign called Motion Pictures Greatest Year. If that was truly to be so, the campaign had to not only ballyhoo big films but also calm unease about world conditions. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria, one instance of the unchallenged spread of fascism in Europe. Foreign distribution accounted for a third of Hollywoods box-office revenue. Stars such as Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich had their largest following in Europe. A European war could totally deprive Hollywood of this market. Bunds, pacts, pogroms and blockades are throttling the release of American pictures in Europe, wrote Edwin Schallert in the Los Angeles Times. Step by step the market in Central Europe is being reduced. Germany and Austria have gone into oblivion. Even if pictures can be sold, there is no remuneration to be derived through direct channels. One solution would be a release schedule full of big-budget films. These could earn big returns in Europe before the inevitable loss of that market. These films could also enjoy longer play outs in the United States, because they would play as high-priced road shows before going into general release.

There were 18,000 theaters in America. Weekly attendance had held at sixty million since 1934, down from the record-breaking ninety million of 1929. What a movie fan paid at any given theater was determined by the Exhibitors Price-and-Time-Fixing Plan. The A pictures opened in movie palaces like the Loews State in downtown Los Angeles or the Pantages in Hollywood. Because of their opulent settings and deluxe presentation, these theaters charged fifty cents general admission, and sixty-five cents for loges. After twenty-one days, an A picture moved to a forty-cent neighborhood theater. After forty-two days, the picture moved to a thirty-cent theater; after sixty-three days, to a twenty-five-cent theater; after ninety-six days to a twenty-cent theater; and, after 126 days, to a fifteen-cent theater, which was probably on skid row.

A films status as a hit or a flop was decided in the first week of its release at the big theaters, which could accommodate thousands of moviegoers. If a film was a bona fide hit, it was held over for a second week. A blockbuster might stay three and four weeks. This was the kind of film that could solve both the antitrust and foreign market problems. Twentieth Century-Fox will not curtail production because of possible European losses, said sales manager Herman Wobber. The company will seek to recapture business through bigger pictures, and subjects that will have appeal for markets such as South America.

Next page