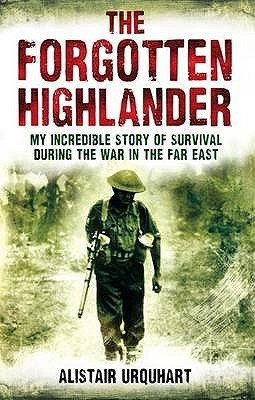

I would like to thank Kurt Bayer of Scottish News Agency who spent many hours quarrying my memory to make this book possible. Thanks are also due to Graham Ogilvy, our editor at Scottish News Agency, and to Stan, our agent at Jenny Brown Associates. I am indebted also to Richard Beswick at Little, Brown who recognised the potential of my story.

The Australian War Memorial and David Martin of Fotopress assisted with photographs. Leslie Bates generously supplied still photographs of the rescue of torpedoed survivors taken by her father Mr Joe Bates, an officer aboard USS Sealion II .

A number of individuals have done so much to keep alive the memory of what we suffered in the Far East. They include: Ron Taylor and Keith Andrews of the Far East Prisoner of War Association; Roger Mansell in San Francisco, who maintains and updates an excellent website that is invaluable for research; and Rod Beattie, who deserves recognition for his sterling efforts in developing the work of the Burma Thailand Railway Memorial Association. US Navy veteran Sid Mouser helped contact the Bates family and hosts moving film of the rescue of the torpedoed survivors on his SubRescue channel on YouTube.

The Gordon Highlanders Museum has also been very supportive and helpful.

My daughter, Joyce, has been a great encouragement and my dear friend Helen Scroggie has been a pillar of strength during the writing of these memoirs. I would like to thank Meg Parkes of the Liverpool Hospital of Tropical Medicine. Last but not least, I would like to thank my consultant and friend Keith Baxby but for whose skill and dedication I would not be here today.

One

Will Ye No Come Back Again?

Everyone remembers how they heard the news. On the morning of 3 September 1939 I was working at the warehouse. As I scuttled around the empty cavern of a building, the sound of my footsteps echoed off the high tin roof. At either end the main doors, which allowed the trucks and carts to drive straight through for loading, were closed. I had the place to myself. It was a Sunday and I wasnt meant to be working but I was an ambitious young apprentice of nineteen, keen to make my way in the world and to get on. The older men, workers who had been with the firm all of their days, said that if you rolled your sleeves up and kept your mouth shut, you could have a job for life. It sounded good to me. For a lot of people the thirties were still hungry and you counted yourself very lucky to have a job with prospects.

I had been in the warehouse since 8 a.m., making up loads for the lorries, to beat the Monday morning rush. Better to get ahead of the game than to chase your tail later. If a jobs worth doing, its worth doing well and all that. At around a quarter to twelve I was searching for crates high on the mezzanine floor that looped around the draughty walls, when I heard footsteps below on the concrete. I tensed up as a voice shouted, Whos up there?

The stentorian tones of the managing director were unmistakable. The big boss! He had slipped in unnoticed through the side door.

Its just me, Mr Grassie, I said nervously, stepping out of the shadows to peer down at my boss and his furrowed brow.

John Grassie looked at me incredulously. I was wearing my usual work attire, including a sleeveless jumper over my company shirt and tie, even though I wasnt supposed to be there Lawson Turnbull & Co. Ltd paid no overtime.

What in Gods name are you doing here, laddie? demanded Mr Grassie. Get off home. Dont you know war has been declared? Your family will want you home.

I did not really appreciate the gravity of those words: war has been declared. I certainly had no conception of how they would change my life. But there was a strange urgency in his voice that made me obey Mr Grassie instantly. He locked up behind me as I set off on my old bike to make the seven-mile journey home. As I hurtled along the deserted streets my mind raced with the possibilities. Chief among them: Would I be called up?

I lived with my parents, auntie, sister and two brothers in a newly built granite bungalow on the western fringes of Aberdeen, the Silver City of the North as it was styled by dint of its glinting granite buildings. When I got home Mum and Dad, Auntie Dossie, my older brother Douglas, younger brother Bill and younger sister Rhoda were all in the living room, grimly gathered around the wireless set.

Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, who only months before had promised peace for our time, had just announced that Britain was at war with Germany. I was born in 1919, the year that the First World War, the War to End All Wars, had officially been concluded. Now here we were a mere twenty years later taking up arms against the same foe. The irony was not lost on me.

After the disaster of the First World War, my father never imagined the powers that be would be stupid enough to lead us into another one. But it transpired that Chamberlain was no match for Hitler. When the conversation inevitably came around to conscription, Father turned to me and said, quite straight-faced, At least your surname begins with the letter U. Youre at the end of the alphabet and the war will be over when they get to you, son. I thought ruefully of the troops in 1914 who were told they would be home by Christmas and kept my doubts to myself.

Unlike so many in the north-east of Scotland, the Urquharts were not a military family. Indeed the motto of the ancient Urquharts was curiously unwarlike for a Highland clan and its admonition to Speak well, mean well, do well could have been written specially for us. My father George was an exceptional mathematician and a teacher of English and Latin at the private commercial college he had helped to found in Aberdeen. He was a clever man. Born the son of humble textile mill workers in the Angus county town of Forfar, he had won a scholarship to the local academy and for the times his progress was an unusual example of social mobility. He was the only one of fourteen siblings to make it out of the mill. But he was systematically diddled by a business partner and his ambitions were never fulfilled. Accordingly we lived in what were politely referred to at the time as straitened circumstances.

Dad had started the business school with a fellow teacher called Billy Trail. While Dad headed the general education side of the college, Mr Trail was in charge of the clerical school, which taught typing and office skills. Mr Trail became a very close family friend. It was the third partner, Mr Wishart, the one who looked after the finances a little too well who did the diddling. In the early 1930s it became apparent that there was not enough money in the business account to pay the wages. Dad and Mr Trail confronted Mr Wishart. He said he would sort the situation immediately. The books were soon corrected but the thieving had gone on for many years. The police should have been called but neither Father nor Mr Trail was very business-minded and they just got on as best they could.

During the First World War Dad had become the first in our family to enlist in the British Army when he joined Aberdeens local regiment, the Gordon Highlanders. Like so many others of his generation, he would know the horrors of the Battle of the Somme and was discharged on medical grounds in 1916, having been gassed and suffering from shellshock. In later life whenever there was a clap of thunder in a storm he would begin to tremble and shake. As a youngster I used to wonder why he did that. It was only years after that I realised the sound brought back the terrors of trench life and the big guns booming overhead, day and night. Like many of his generation he never talked of his wartime experiences. Later, after my own hellish war, I would learn why.