Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

PREFACE

In the summer of 1986, I received a last-minute call asking me to step in as a substitute interpreter for Taniguchi Sumiteru, a fifty-seven-year-old survivor of the 1945 Nagasaki atomic bombing. Taniguchi was in Washington, D.C., as part of a speaking tour in the United States. I had just met him the night before when I attended one of his talks. Over the next two days, I spent more than twenty hours with Taniguchi, listening to and interpreting his story in public presentations and private conversations.

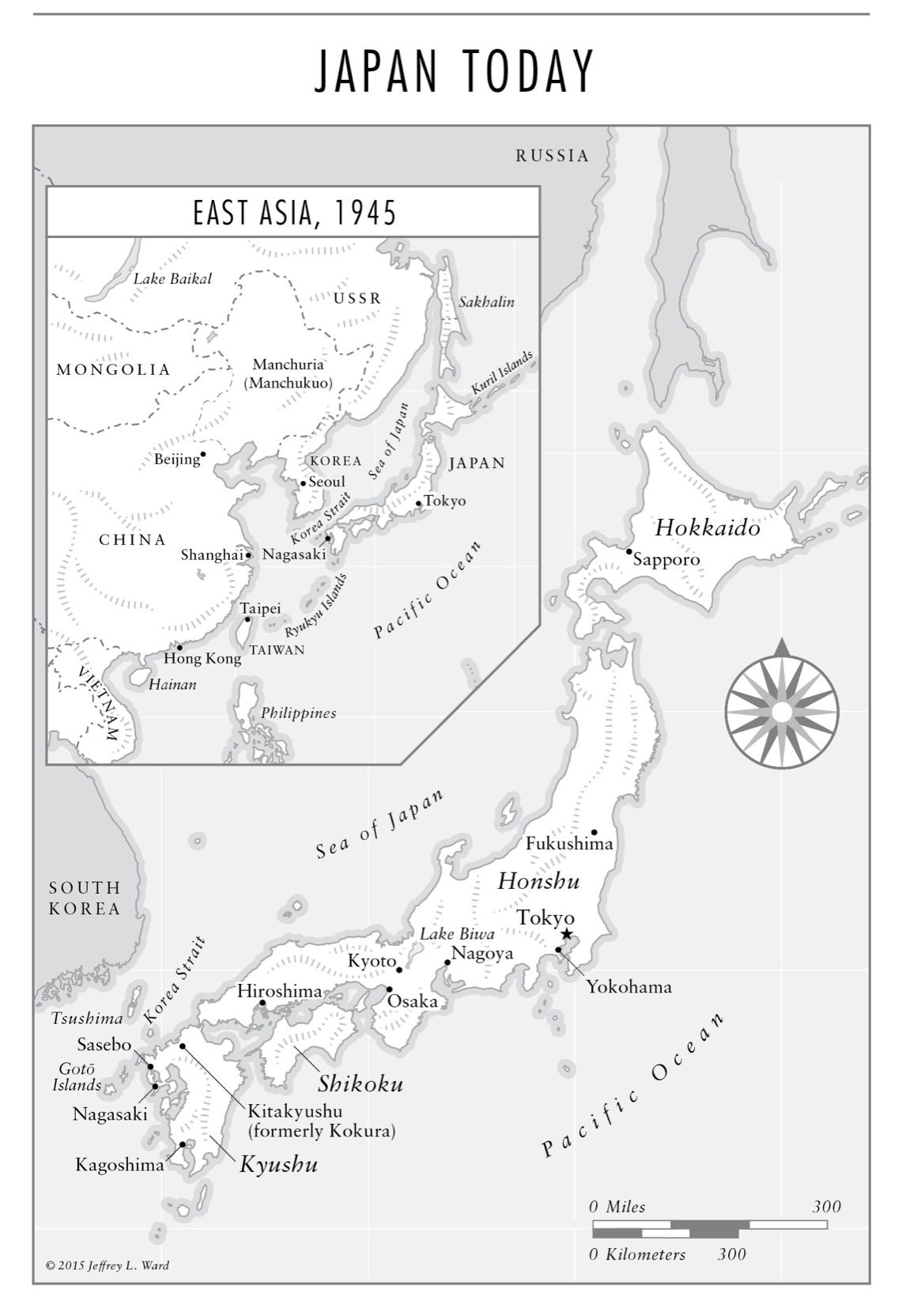

Years earlier I had lived in Yokohama, just south of Tokyo, as an international scholarship student. At sixteen, I was placed with a traditional Japanese family and attended an all-girls high school in the neighboring city of Kamakura, Japans ancient capital. Nearly everything was foreign to me, including the languageand I had little knowledge of the Pacific War and the atomic bombings that had taken place thirty years earlier. Later that year, after my language skills and integration into Japanese life had improved, I traveled to Nagasaki for the first time during my high schools senior class trip to southern Japan. Inside the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum, I stood arm in arm with friends who had embraced me as their own, staring at photographs of burned adults and children and the crushed and melted household items on display. In one of the glass cases, a helmet still had the charred flesh of a persons scalp stuck inside.

The memory of Nagasaki stayed with me into adulthood. And yet, as I listened to Taniguchi speak in a dimly lit church hall near downtown D.C., I realized how ignorant I still was of the history of the Pacific War, the development of the atomic bombs, and the human consequences of their use.

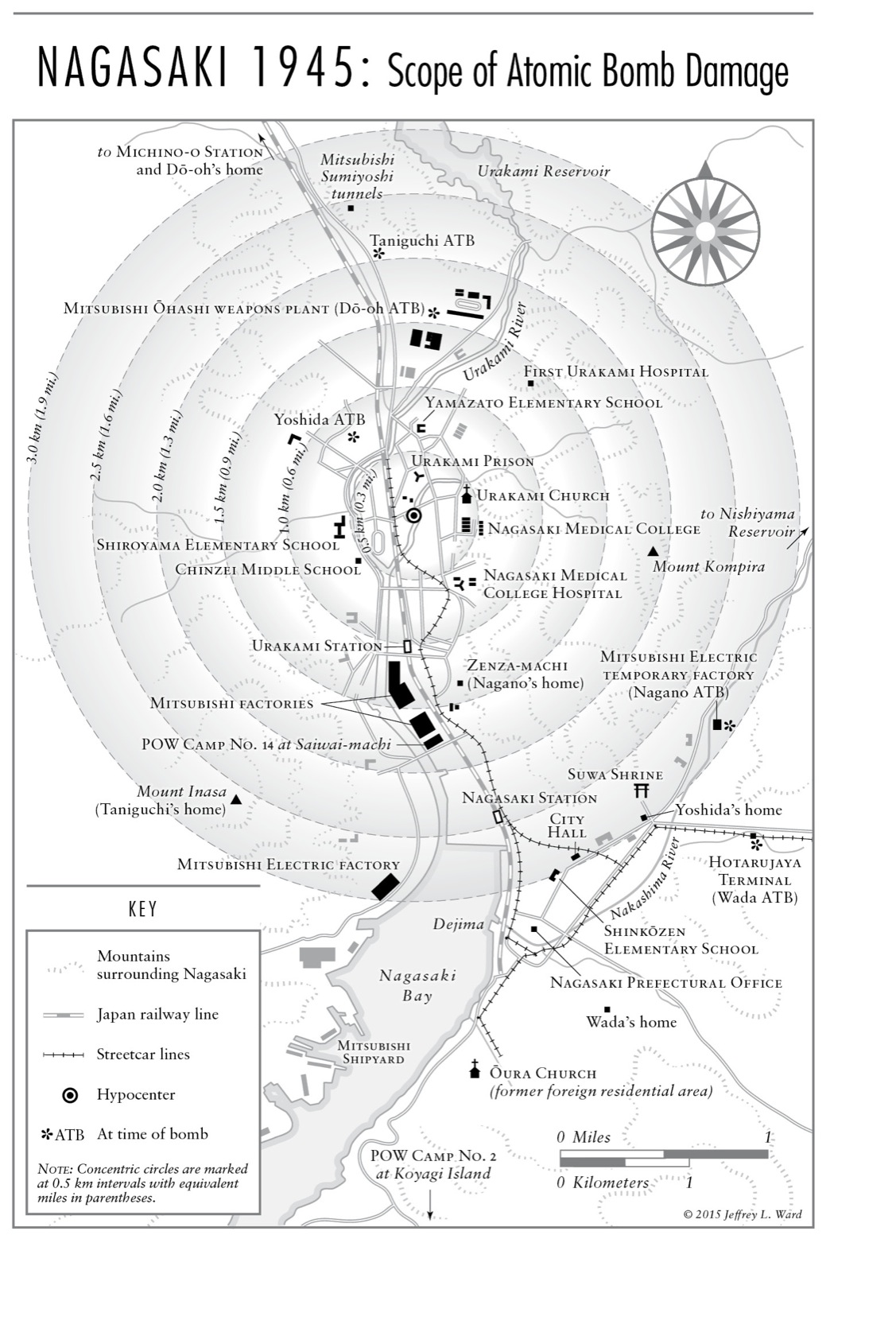

Taniguchi was sharply dressed in a gray suit, a white dress shirt, and a deep purple and navy striped tie. On his left lapel he wore a pina white origami crane set against a red background. His thick black hair was combed neatly to the side. Smallmaybe five foot sixand noticeably thin, he told his story quietly, the syllables toppling one upon another: At 11:02 a.m. on August 9, 1945, sixteen-year-old Taniguchi was on his bicycle delivering mail in the northwestern section of the city when a plutonium bomb fell from the sky and exploded over a Nagasaki neighborhood of about thirty thousand residents. In the flash of the explosion, he said, his voice trembling, I was blown off the bicycle from behind and slapped down against the ground. The earth seemed to shiver like an earthquake. Although he was over a mile away, the extraordinary heat of the bomb torched Taniguchis back. After a few moments, he lifted his head to see that the children who had been playing near him were dead.

As he spoke, Taniguchi held up a photograph of himself taken five months after the blast during his protracted stay at a hospital north of Nagasaki. In the photograph he is lying on his stomach, emaciated. Down one arm and from neck to buttocks where his back would be, there is no skin or flesh, only exposed muscle and tissue, raw and red. As Taniguchi finished his speech, he made eye contact with his audience for the first time. Let there be no more Nagasakis, he appealed. I call on you to work together to build a world free of nuclear weapons.

After his presentation, I drove Taniguchi to the small house outside of D.C. where he was staying. We sat on the front porch; the light from the front hallway allowed us to see each other only in shadow. I plied Taniguchi with questions about the bombing and the weeks, months, and years that followed. He handed me a small stack of photos that resembled mug shotsmedical photos, I presumedfull-body back, front, and side views. They showed Taniguchi, perhaps in his forties, naked except for his traditional Japanese undergarment. His entire back was a mass of rubbery keloid scars. Near the center of his chest, deep indentations still remained where his skin and flesh had rotted, the result of lying on his stomach for nearly four years. It was a time, he told me, when the pain was so excruciating that every day he had begged the nurses to let him die. I asked Taniguchi which memories from his life were most important to him. Just that I lived, he said. That I have lived this long. I have sadness and struggle that goes with being alive, but I went to the very last edge of life, so I feel joy in the fact that Im here, now.

By the time Taniguchi left Washington, I longed to more fully understand what it took for him and others to live day by day in the face of acute physical pain, psychological trauma, and a personal history split in half by nuclear war. What kinds of radiation-related injuries did they experience, and what did survival look like in the days, months, and years that followed the attack? And how was it that I, who had lived in Japan and had been educated in excellent public high schools and universities in the United States, had no specific knowledge about the survivors of the atomic bombings? Why do most Americans know little or nothing about the victims experiences beneath the atomic clouds or in the years since 1945?

____

As single weapons, the atomic bombs used against Japan were unmatched in their explosive force, intense heat, and ability to cause instantaneous mass death. Radiation doses larger than any human had ever received penetrated the bodies of people and animals, causing cellular changes that led to death, disease, and life-altering medical conditions. More than 200,000 men, women, and children died from the Hiroshima and Nagasaki attackseither at the time of the bombings or over the next five months from their wounds or acute radiation exposure. In the years that followed, tens of thousands more suffered from injury and radiation-related diseases. An estimated 192,000 hibakusha (atomic bombaffected peoplepronounced hee-bakh-sha ) are still alive today. The youngest, exposed in utero to the bombs radiation, will turn seventy in August 2015.

Many critically acclaimed books have addressed the United States decision to use the bomb, but few have featured the eyewitness accounts of atomic bomb survivors. Those that have, such as John Herseys Hiroshima and several collections of hibakusha testimonies, focus almost exclusively on the immediate aftermath of the bombings; stories detailing the brutal long-term physical, emotional, and social manifestations of nuclear survival have rarely been told. As the second city bombed, Nagasaki is even less known than Hiroshima, which quickly became the global symbol of the atomic bombings of Japan. The invisibility of Nagasaki is so extreme that the bomb is often expressed as a singular event for both cities, without regard for the fact that the two atomic bombings were separated by time, geography, and the need for distinct analysis of military necessity.