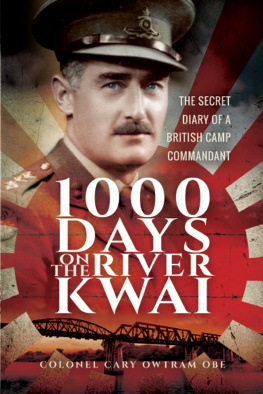

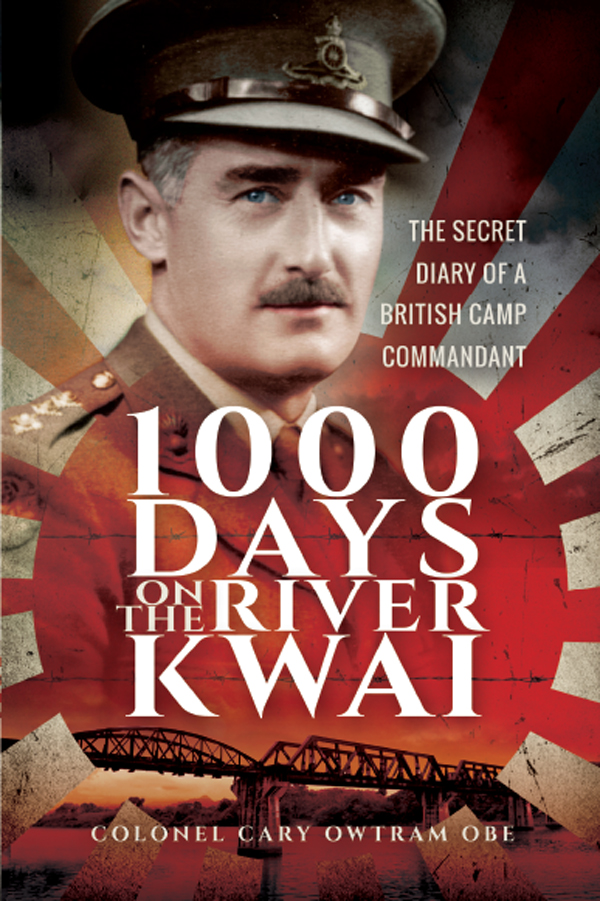

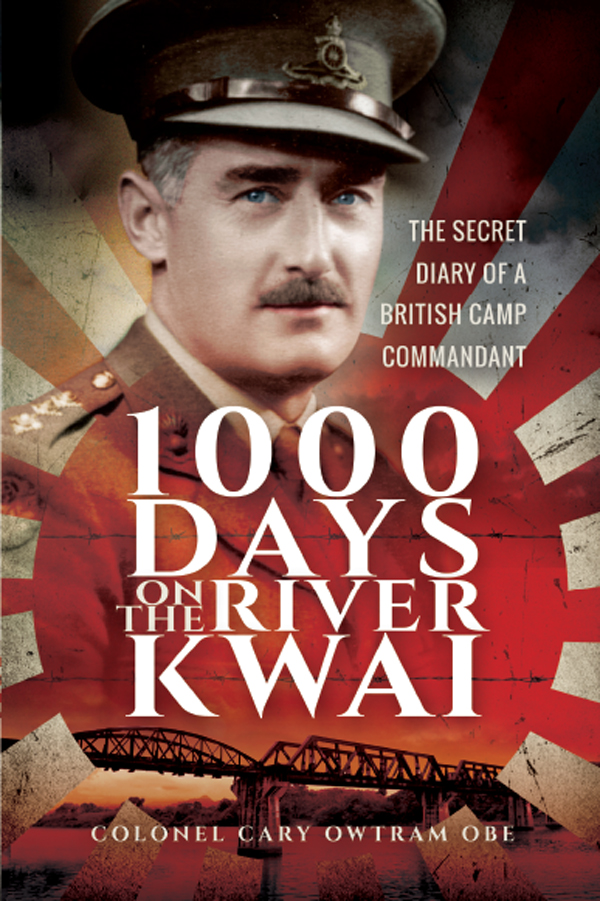

1000 Days on the River Kwai

1000 Days on the River Kwai

The Secret Diary of a British Camp Commandant

Colonel Cary Owtram OBE

First published in Great Britain in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright The Estate of Cary Owtram OBE, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 780 9

eISBN 978 1 47389 782 3

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 781 6

The right of Cary Owtram OBE to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Books Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Transport, True Crime, Fiction, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Seaforth Publishing, Wharncliffe and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED 47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Their bodies are buried in peace, but their name liveth for evermore.

Ecclesiasticus 44:14

Foreword

T his book, based on his secretly kept wartime diaries, was written by Colonel Cary Owtram a few years after his return from more than three years captivity in Thailand as a prisoner of war of the Japanese. At the time he failed to find a publisher, and the manuscript was given to the Imperial War Museum along with the original diaries. Now, more than sixty years later, it is being published, with the addition of a postscript in which his daughters Patricia Davies and Jean Argles add their memories of the effect on the family of his imprisonment and eventual release.

The text is exactly as it was written in 1953, with one exception. It will be clear to the reader that the Author returned from the war with an understandably deep hatred of the Japanese, and this was reflected in some of his language. Certain terms that were commonplace in the aftermath of the war (for example, referring to the Japanese as Nips) are now unacceptable, and such references have been toned down, although hopefully without obscuring the strength of the authors feelings.

Preface

W hen I returned home in October 1945, after three and a half years as a prisoner of war of the Japanese, I brought with me a diary which I had written up regularly for a greater part of the time, as well as a number of records of matters of more particular importance or interest in connection with our existence. As the Japanese searches for such things became increasingly thorough, I buried them in a sealed bottle in a British soldiers grave, but was able to retrieve them at the end of hostilities.

Friends and relations have urged me from time to time to write an account of our experiences as PoWs and so, having records to refer to where owing to the passage of time memory might have failed me, I have written the story of our existence for one can hardly call it anything else as seen from a rather different viewpoint to that of other published accounts.

British Camp Commandant of the largest PoW camp in Siam (Thailand) for approximately two years, I probably had a wider knowledge of what was going on in all directions than some of those whose spheres of activity were necessarily more limited so far as administration was concerned.

This book is written as a tribute to the unconquerable spirit of all British, Australian, American and Dutch PoWs in Siam, compelled by brute force to perform a superhuman task far beyond the limits of normal human endurance, but who, by their faith in God, loyalty to each other and sheer guts, were given strength to survive. It is dedicated to the memory of many thousands more whose bodies are buried in Siam and Malaya (Malaysia).

They lie amid the peace and beauty of a picturesque land, but their memory lives forever with us who survived.

The names I have used throughout are real, and I trust that their owners will forgive me for taking this liberty.

I am grateful to several people for the production of this book. To my wife and family for encouragement and help during the time I was writing it; to Mrs Vera Currier for many hours of typing and correction; and to John F. Leeming, himself an author and a friend of long standing, for a great deal of useful advice in putting it into shape.

Cary Owtram

December 1953

Chapter 1

Outward Bound

O n a murky, wet Sunday in September 1941, the 137 th Field Regiment, in which I was then serving as Second in Command, embarked at Liverpool in SS Dominion Monarch . That evening, we nosed our way down the Mersey to join a large convoy collecting in the Irish Sea and consisting of about twenty liners and cargo boats, with an escort of cruisers and destroyers.

This was the beginning of an active share in the war, for which we had been training for two years, and everyone was, rather naturally, keyed up with a sense of excitement and anticipation, particularly as the majority of us had little idea of our ultimate destination. All we knew was that a tropical country was indicated by the kit we had drawn.

Passing slowly down the Mersey and over the bar, we anchored for the night while the rest of the convoy formed up. Next morning, we moved out into the Irish Sea, and as the coastline faded in the distance, the last bit of England we were to see for many a long day was the top of Blackpool Tower disappearing in the haze, a reminder of the early days of the war when many of us had spent the first six months there the birthplace of the regiment.

Our course took us almost to the North American coast and then south in a wide sweep back to Freetown, Sierra Leone, where we spent two sweltering days gazing from the ship at the sinister-looking coast, clad with Rackham-like trees and thick, tropical jungle. From there we proceeded to Cape Town, where the memory of the welcome we received will remain with us always. The hospitality showered upon us was positively embarrassing, and our four-day stay was all too short.

From Cape Town we sailed across the Indian Ocean, touching for a few hours at Colombo, where we picked up the ill-fated Repulse as part of our escort; and on 29 November we drew alongside the quay in Keppel Harbour at Singapore, our final destination.

After more than eight weeks at sea with little opportunity for exercise, the entire regiment of seventeen hundred excited men hurled themselves at the job of unloading our baggage on to the quayside, to the accompaniment of rattling derrick chains and screaming Chinese dock workers. After the enforced idleness of the sea voyage, sweat poured off us as we heaved and pushed the heavy baggage beneath the blazing heat of a tropical sun until everything was out of the ship.

The same evening, most of the regiment moved by train to a little village called Kajang, just south of Kuala Lumpur, some 250 miles north of Singapore, leaving the drivers and a fatigue party behind to unload our guns, vehicles and stores, which arrived on a slower ship a day or two later.

Next page