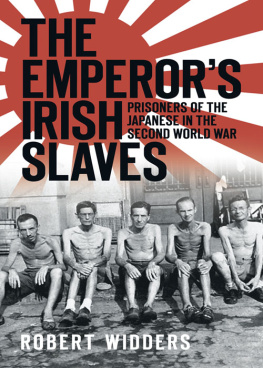

This is the story of 400 prisoners of war who were captured by the Japanese on the fall of Singapore. Three and a half years later, when the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki meant the end of the war, 136 of them were released but the other 264 died in captivity.

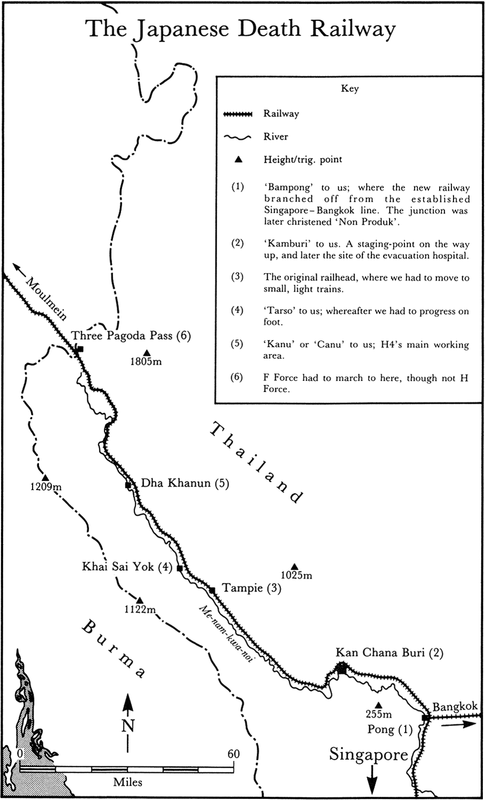

After over a year of idleness but increasing boredom and hunger at Changi on Singapore Island, they were sent up country as one of the numerous working parties to help the Japanese with the construction of the railway through the jungles of Siam, to link Siam with Burma. Five months of working were followed by three months in a recuperation camp: but in those eight months nearly two out of every three died, from common starvation or from the delights of cholera, malaria, beri-beri, dysentery, or gangrene.

It was quite a long railway, but for every sleeper laid it cost the life of one POW or of one coolie the natives drafted up from the rubber plantations of Malaya, when the Japs ran out of working POWs, the majority of whom had irritatingly died.

Eight short months seemed quite long at the time with two out of every three dead.

Singapore had fallen.

That afternoon, a staff officer, accompanied by an interpreter, had gone out through the lines under a large white flag to Bukit Timah, a small hill just to the north of the city, to sign the unconditional surrender of the British to the invading Japanese forces, with the prime object, in the words of General Yamashita, to save the innocent civilian population from the horrors of an all-out assault on the city.

He was, of course, quite rational. There were over a million civilians in the city Malays, Chinese, Tamils, and whatever. They were already suffering, and the small British Army had no hope whatsoever of protecting them. It was not that we were short of men, or of guns, or of ammunition we were short of water.

The citys water supply normally came in from the mainland over the causeway, feeding two small reservoirs on the Island: but the causeway had been blown up (by us) towards the end of the retreat down the Malaya mainland, and the Japs had now overrun the reservoirs as well. They had cut off all supplies of water to the city, and we had had none for five days.

No water meant no sanitation. In a hot climate, just 80 miles north of the Equator, the result was dramatic. Disease, in the form of dysentery and cholera, became no mere remote threat, but an immediate and dire certainty. Not merely for the innocent civilians, but for the British Army as well, as witness the Cathay Building.

We had a General Headquarters, but it only had one corps, and so 3rd Indian Corps was the effective Fighting Headquarters. I was in command of the 3rd Indian Corps Signals Regiment (or the rump of it as most of our troops had been siphoned off a fortnight previously to provide reserve infantry because corps was short of fighting men), and our job was to run the communications for 3rd Corps.

Corps HQ had moved down to the centre of the city two weeks earlier, with a not very happy choice of location. The Cathay Building was brand new, and was the highest skyscraper in the city, and corps established itself on the second and third floors. This despite loud protests from the Australian Division, who were already using the ground and first floors as their base hospital, and didnt like a fighting HQ moving into the same building with their Red Cross flag flying from the roof. Nevertheless, corps moved in, and the Red Cross flag continued to fly.

Now, this skyscraper housed over a thousand souls and after five days without any water, the whole place stank to high Heaven. Every loo had been used over and over again, but there was no water with which to flush them. It was no good saying get a bucket of water, because there was nowhere to fill a bucket. A thousand sets of bowels and a thousand bladders crying out for relief were causing the situation to deteriorate hourly, and the Cathay was no longer a very nice place to be.

There had been a lot of fine talk back in London about Singapore being defended to the last man, and to the last round, but we didnt surrender because of lack of men or of ammunition we surrendered because of lack of water, for the million civilians as much as for the Army. The finest military equipment in the world wont help you if you are unwashed, dirty, smelly, and above all dehydrated. Anyway, we were thirsty, and we capitulated.

It was an eerily quiet evening and night after the white flag party had gone out, and the firing gradually died down and then eventually petered out.

We had been told to quit our operational positions and to return to our billets or sleeping areas, which for my little unit meant leaving the Cathay and going to the museum 300 yards away where our off-duty personnel slept and ate. Fortunately, the museum was surrounded by lawns and flowerbeds, and so we had been able to dig latrines which came as a great relief, in all senses of the word, particularly to those who had been cooped up in the stench of the Cathay.

We waited all night, and at about 9 a.m. the Japs moved in. They came in by the lorry-load, all standing up and clutching little paper Jap flags a large red dot on a white background, known to them as the RisingSun but to us as the PoachedEgg.

They showed no sign of emotion whatsoever. Had it been the victorious British entering a conquered city, the troops would have been waving their flags and shouting and singing (and most of them at least half drunk): but the Japs stared steadfastly forward, without uttering a sound, and not even waving their little flags. They took not the slightest notice of us waiting by the roadside. It was even more eerie. Mark you, as we later learnt, when they got past us and down into the Chinese native quarter, things were different, and within twenty-four hours there was not a virgin to be found amongst the one million population.

We stayed where we were, and very soon got some preliminary orders. There were to be no separate officer camps and other rank camps, as there were in Germany. Officers would stay with their men, and whole units would stay together, with one important exception: we would be separated into Whites and non-Whites.

I would explain that the official name of Corps was 3rd Indian Corps, and that the two original divisions were both Indian Divisions. In each Indian Division you had two brigades, each with two Indian Battalions and one British Battalion. The Indian Battalions had mostly white officers but all of the soldiery were Indians. Specialist troops like Engineers and Signals were all-white.

In addition to the two original divisions, we had the Australians, who were naturally all-white; and the poor wretched 18th Division, which had only arrived in Malaya from England as we were scampering back over the causeway, and the campaign was nearly over. Furthermore, by some superb piece of administrative planning, whilst the troops themselves were landed at Singapore, all their artillery and armoured troop carriers had been sent to Java, and so, armed with little else but their rifles, most of the 18th Division walked off their ships and almost immediately into the bag, with three and a half years in prison camps ahead of them.

All in all, there were a lot of Indians, but there were still more Whites, including the Australians and the 18th Division. Approximately 47,000 non-Whites, and 53,000 Whites, so roughly 100,000 altogether.

The Japs were at a loss there were more of us than they had expected. They separated us by colour, not having heard of racial discrimination or of the rights of ethnic minorities, and we were to go to two huge camps, the Whites to Changi, and the non-Whites to Farrer Park.