First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Ellie Taylor, 2015

ISBN: 978 1 47385 788 9

PDF ISBN: 978 1 47385 791 9

EPUB ISBN: 978 1 47385 790 2

PRC ISBN: 978 1 47385 789 6

The right of Ellie Taylor to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Palatino by

Replika Press Pvt Ltd, India

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to all those who so kindly helped me to research my fathers time in captivity. My thanks go to Keith Andrews and to Meg Parkes for their help and encouragement in the very early stages of my research, and particularly to Andrew Snow of the Thai-Burma Railway Centre, who so patiently answered my many questions, enabling me to establish a timeline of Dads movements between various POW camps and so produce this account of his experiences.

List of Illustrations

11. The steel bridge at Kanchanaburi (Kanburi), on which Dad worked in 1945, photographed in 2003.

Foreword

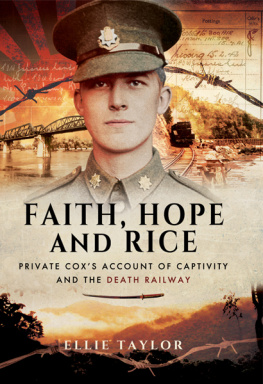

A little boy places poppies on a section of railway track which had been built over seventy years earlier between Thailand and Burma. He is too young to understand the significance of that track, only that he is doing something in memory of his great-grandfather, one of the many thousands of men forced by the Japanese to build it. Between 1942 and 1943, over 60,000 British, Australian, Dutch and American prisoners, together with countless thousands of conscripted native labourers, were put to work by the Japanese on the construction of over 250 miles of track between Ban Pong in Thailand and Thanbyuzayat in Burma, among them, my father, Tony Cox. Though essentially what follows is his story, in some respects it may also be seen as that of the many others who experienced the brutality, malnutrition, deprivation and disease which characterised life on what became known as the Death Railway. Some 12,000 Allied prisoners and an estimated 90,000 native labourers died during the construction of the railway, the purpose of which was to provide a supply line for Japanese troops. Camps were built along the entire length of the railway as work on it progressed, housing thousands of prisoners. Many of them, like Dad, remained at these camps for the duration of the war performing maintenance tasks on the track, and there were many more deaths during this time. My father was one of those fortunate enough to have survived but, sadly, did not live long enough to meet his great-grandchildren. However, because of the notes he made of his experience of captivity shortly after he was repatriated, they will one day have the chance to read his story. It is a story which is told in the hope that the sacrifice and suffering of those who toiled on the Thai-Burma Railway as prisoners of the Japanese will never be forgotten.

Some twenty-five years before the fall of Singapore which saw him taken a prisoner of war, Dad was born into the poverty of a south London tenement block at a time when an earlier war was being fought. He grew up to have no memories of his own father, a sapper in the Royal Engineers, who returned from fighting on the Western Front in 1916 having suffered irreparable damage to his lungs and died before Dad was two years old. The strain of trying to raise five children on her own proved too much for his mother and within a couple of years, shortage of money resulted in Dad and two of his four siblings being placed in the care of a charitable foundation which provided for homeless and destitute children. Thereafter they grew up in a Catholic childrens home in Surrey, with few visits from other family and no option but to try to make the best of it. Dad said that whilst he had no particularly fond memories of his time there, it had taught him valuable lessons about communal living and the value of friendship which were to serve him well in years to come. It had also given him the basics of the faith from which he was to draw much needed strength and comfort during his captivity. However grim life in the childrens home had been, any negative feelings about it were, no doubt, eclipsed by what followed some years later at the hands of the Japanese. It was also whilst he was there that he acquired the name which he later adopted for most of his adult life, it apparently having been the practice of the home to allocate an alternative name to all of the children who came into its care, many of whom were orphans. Thus, although the explanation behind the choice of name was somewhat vague, he acquired the name Anthony, which, as it happened, he much preferred to the Hugh Frederick his parents had chosen for him.

After leaving the home, Dad worked as a porter until he was old enough to join the Army. Given what had happened to his father, he can have harboured no illusions as to the possible consequences should Britain find herself at war once more, and in 1934 enlisted in the East Surrey Regiment. Officialdom required him to do so using the names which appeared on his birth certificate, and to his pals in the Army he was Private Fred Cox. Following a period spent in England, he served in India and the Sudan and China, and was stationed in Shanghai at the outbreak of the Second World War. He spoke of his pre-war Army life with great pride, and said it had given him opportunities to see the world which he would otherwise never have had. He talked of the friends he had made and one friend in particular, Jim, who had enlisted at the same time and served alongside him throughout their time in the Army. The East Surreys were undergoing combat training in northern Malaya when the Japanese invaded in December 1941. The battalion suffered very heavy casualties, with almost two-thirds of their number killed, and were eventually forced to retreat down the Malayan peninsula to the island of Singapore where, on 15 February 1942, along with some 50,000 others, Dad became a prisoner of the Japanese for the next three and a half years.

When war broke out in 1939, my mother, Joan, had been working as a shorthand typist in South East London but had wanted to do something to support the war effort so she decided to train as a Red Cross nurse. After completing her training in Portsmouth, she was posted to Ceylon as a Mobile VAD in 1942. By the time Dad was admitted to St Peters Royal Naval Auxiliary Hospital in Colombo in September 1945, shortly after his liberation from a prisoner of war camp in Thailand, Mum had been a nurse there for three years. (Unbeknown to either of my parents at the time, they had actually spent their childhoods living just a few miles apart in Surrey, but they were not destined to meet until they had each travelled halfway around the world.) After something of a whirlwind courtship, they married within weeks of their return to England. Three and half years captivity had taken its toll on Dads health and, like his father before him, he was discharged from the Army on the grounds of being unable to fulfil army physical requirements. He subsequently joined the Fire Service, but before long this role also proved to be too physically demanding for him. However, the physical legacy of his years as a prisoner of war was only part of the problem.

Next page