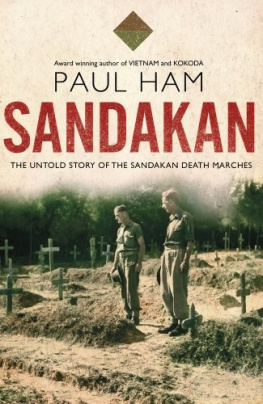

SANDAKAN

THE UNTOLD STORY OFTHE SANDAKAN DEATH MARCHES

PAUL HAM

A WilliamHeinemann book

Published byRandom House Australia Pty Ltd

Level 3, 100Pacific Highway, North Sydney NSW 2060

www.randomhouse.com.au

First publishedby William Heinemann in 2012

Copyright PaulHam 2012

The moral rightof the author has been asserted.

All rightsreserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any personor entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or byany means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under thestatutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage andretrieval system without the prior written permission of Random HouseAustralia.

Addresses forcompanies within the Random House Group can be found at www. randomhouse.com. au/offices.

National Libraryof Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Entry

Ham, Paul.

Sandakan/PaulHam.

ISBN 978 1 86471140 0 (hbk.)

Sandakan(Concentration camp) History.

Prisoners of war Australia.

Prisoners of war Great Britain.

Prisoners of war Malaysia Sandakan.

Concentrationcamps Malaysia Sandakan History.

World War,1939-1945 Prisoners and prisons, Japanese.

940. 547252

Jacket images:front Privates Bowen and Dobbin at the grave of Captain Matthews, September1945, Australian War Memorial 118550; back iron gates at the SandakanMemorial Park, Sabah Louise Heusinkveld/Alamy Jacket design by RichardShailer Maps by Laurie Whiddon, Map Illustrations. The Death March route isbased on the map published by the Australian Government Department of Defencein April 2012

Internal designby Xou Creative, Australia

Typeset inGaramond by Xou Creative, Australia

Printed inAustralia by Griffin Press, an accredited ISO AS/NZS 14001:2004 EnvironmentalManagement System printer

Random HouseAustralia uses papers that are natural, renewable and recyclable products andmade from wood grown in sustainable forests. The logging and manufacturingprocesses are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of thecountry of origin.

Dedicated to theAustralian and British prisoners of war in Borneo who never came home, the fewwho did, and the local people who tried to save them

Paul Ham

Sydney

Australia

Tenno Heika

His Imperial Majesty The Emperor of Japan

The Imperial Palace

Tokyo

Japan

October 2012

Your Majesty,

Youmay think it impertinent of me, an Australian historian, to presume to addressthe Emperor of Japan. No doubt, many of your countrymen will think so and urgeyou to ignore this unsolicited letter.

ButI write to you in an effort to find some connection between our countriesbeyond trade, tourism and the memory of the most terrible conflict our worldhas known. We are still recovering from that experience. Of the 50 millionpeople who died in the Second World War, more than half were Asian people andAllied servicemen and women, the victims of Japanese aggression.

Iwrite not in anger or bitterness, but rather in the spirit of respect andfriendship. I do not share in the slightest degree the racial intolerance ofsome of my countrymen and women, whose hatred of the Japanese people festersdecades after the last drop of blood fell to earth in the dying months of thePacific War. But it is absurd and wrong to hate a whole people, as RobertMenzies, a former Australian prime minister, reminded us in 1942. FewAustralians seem to realise that Japan was our ally during the First World War,and treated German and Russian prisoners of war with exemplary care andrestraint.

Itherefore appeal to our shared sense of humanity, which recognises no social orcultural distinctions, transcends race, religion and the colour of our skin,and reaches out to embrace the higher attributes of human nature: justice,compassion and mutual goodwill. It is in this spirit that I present you with mybook, Sandakan: The Untold Story of the Sandakan Death Marches (RandomHouse, 2012), the history of a little-known war crime that occurred between1942 and 1945 in Borneo, when the island was an outpost of the Japanese Empire.It is the story of the agonising last days and needless deaths of more than2400 Australian and British prisoners of war. Enslaved for three years in aJapanese prison camp at Sandakan, many died of disease, malnutrition andappalling treatment. Some 1100 survivors were then force-marched into the heartof the island. Six came home a 99.5 per cent death rate, the worst of anyprisoner-of-war camp in the Pacific or European theatres of the Second WorldWar.

Thevictims of Borneo were starved, tortured, shot, bayoneted or beheaded. Manydied of untreated illnesses or starvation. One was crucified and disembowelled,according to a witness. The Death Marches were the biggest killer: sick andhungry men were forced to carry heavy loads through jungle and swamp, and overmountains, until they collapsed from exhaustion or disease or hunger, whereuponthe guards shot or clubbed them to death. It was a policy of mass extermination.The killing continued until 27 August 1945, nearly a fortnight after thearmistice. These crimes were committed in the name of the military regime overwhich your father held supreme command, under Article 6 of the ImperialJapanese Constitution.

Thefacts only partly convey the horror of the individual stories stories of menwho experienced unearthly suffering. Chaplain Harold Wardale-Greenwood, forinstance, was an officer who led his troops on the Death Marches with hisChristian god in his heart and hope for his men in his head, but he lost hisfaith in the face of such cruelty days before he succumbed to sickness. CaptainLionel Matthews, arrested for running an underground smuggling operation inSandakan Prison Camp, was tortured to within an inch of his life but neverbroke. After each torture session, he would tap Morse signals on his knee towarn his fellow prisoners of what they were about to endure at the hands of theKempei-tai. Added to this were the countless acts of bravery and resistance bysoldiers beaten, starved and exhausted beyond reach of hope or deliverance,prodded at bayonet point to a lonely death in the sodden jungles of Borneo.

Thesefacts were laid before the War Crimes Tribunal, which convened in a tent on abeach in Labuan in January 1946. They outraged every scrap of humanityenshrined in the Geneva Convention, to which Japan was not a signatory, but bythe terms of which your country had promised to abide. Many of theperpetrators, Japanese and Formosan, were executed; most were imprisoned andthen freed, in the 1950s, under a general amnesty.

Sincethe end of the war, no Japanese government has recognised or accepted historicresponsibility for the Death Marches in Borneo. None has apologised to,recognised or made an effort to compensate the Australian and British familiesand the native people of Borneo for the atrocities that left behind so manywidows, fatherless sons and families in mourning for their boys. Of course,nothing can compensate a family for the loss of a father, son, husband orbrother except his return.

Japanssilence on these crimes crimes that will disgust every human heart capable offeeling implies a reluctance to accept responsibility for them and redoundsto the disgrace of the Japanese nation.

Thatdoes not mean the victors are immune from the same charge. Any honest analysisof the Pacific War accepts that the Allies committed unconscionable acts ofwanton barbarity. I am the author of HiroshimaNagasaki , a history of the atomic bombs. Only the wilfullyignorant or prejudiced could fail to conclude, after examining the evidence,that the nuclear attacks on your country were not only crimes against humanitybut also militarily unnecessary. Was the breaking, burning or irradiation ofhundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians justified as revenge for PearlHarbor, as the American Government claimed at the time? We debase ourselves,and the history of civilisation, if we accept that Japanese atrocitieswarranted an American atrocity in reply.

Next page