Paul Ham - Kokoda

Here you can read online Paul Ham - Kokoda full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: HarperCollins Publishers (Australia) Pty Ltd, genre: History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

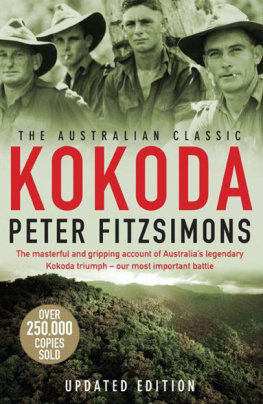

Kokoda: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Kokoda" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Kokoda — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Kokoda" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For my son, Ollie; my brother, Ian; and the poor, bewildered bloody infantry

I mean the truth untold,

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Wilfred Owen, Strange Meeting

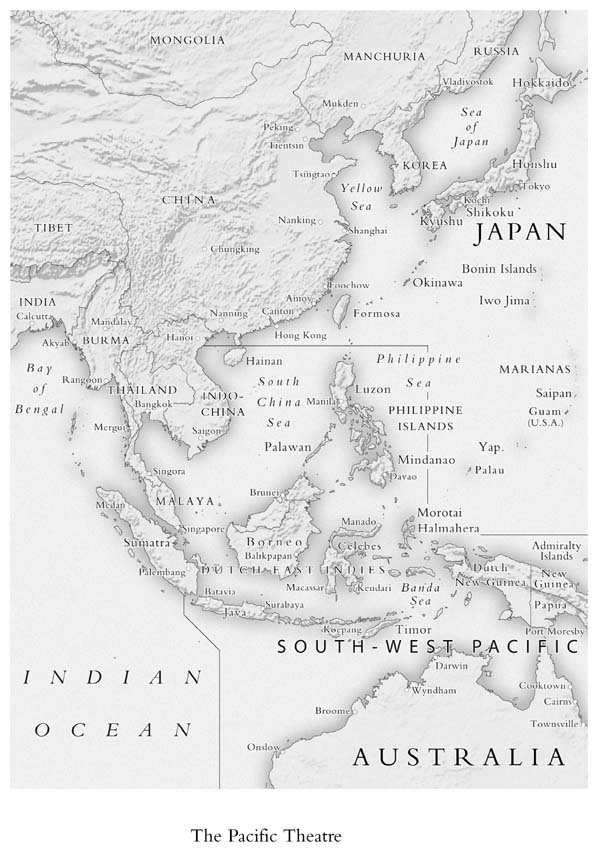

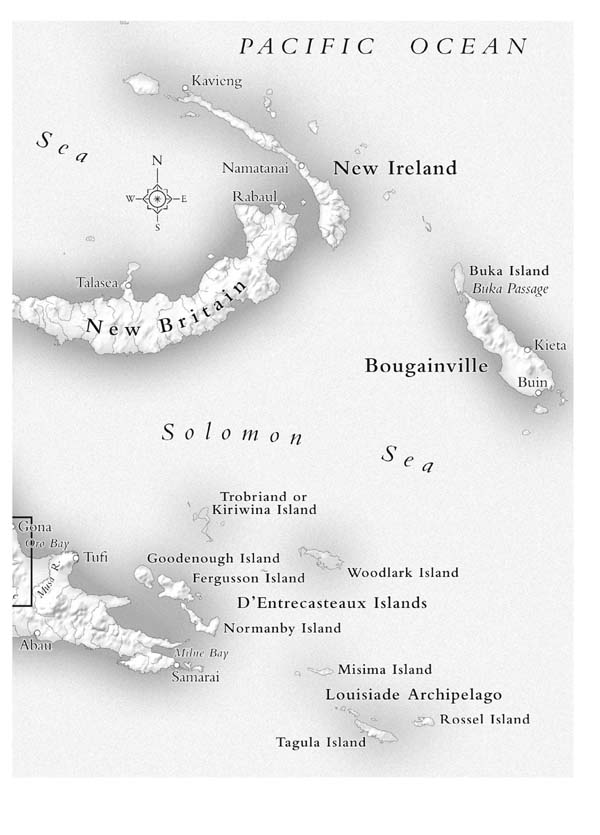

Kokoda Track or Trail?

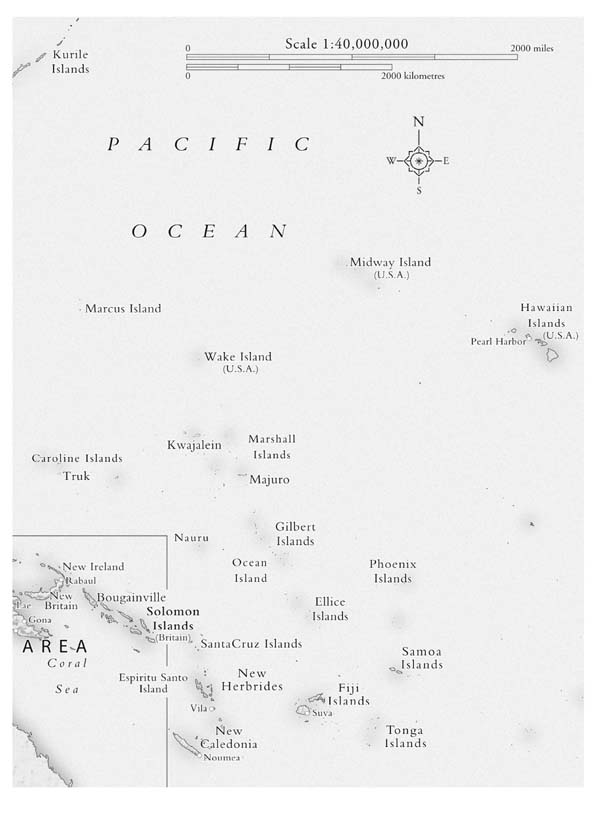

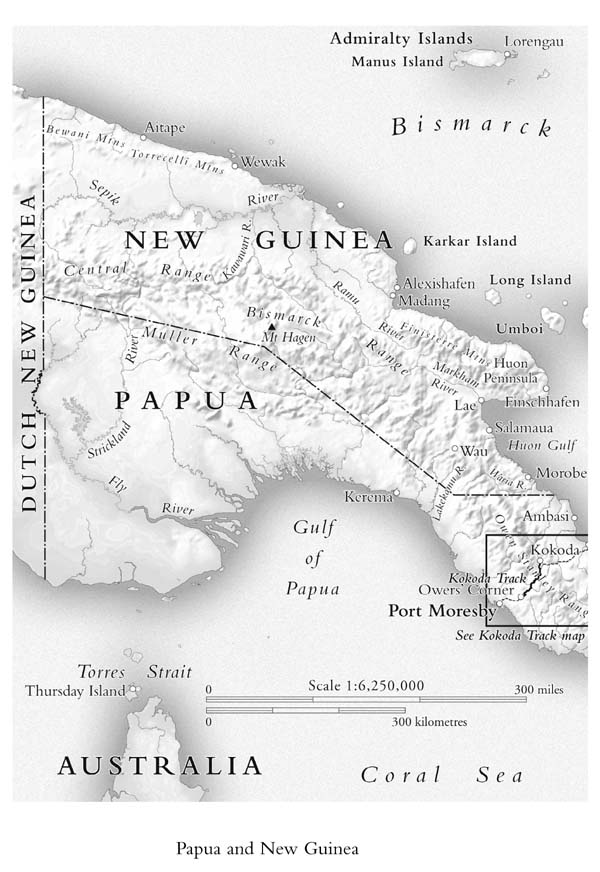

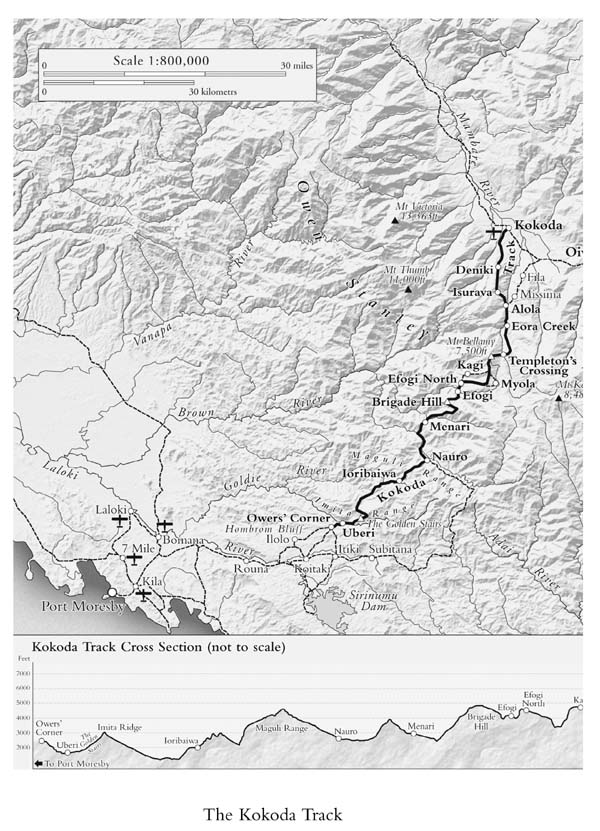

I glimpsed a kind of hell during the writing of this book. The Kokoda campaignby which I include the battles of the Kokoda Track, Milne Bay and the Papuan beachesis exceptional in military history. In terms of casualty numbers, of course, it was insignificant alongside the huge pitched battles for Europe and the Soviet Union. But such quantitative judgments mean little to the mother, father, wife, brother, sister or child of a dead soldier. What made this campaign uniquely grim was the proximity of the fighting and the extraordinary terrain over which the two armies clashed. It was indeed, at times, a knife fight out of the stone age, as historian Eric Bergerud wrote. The Kokoda campaign is distinguished for three other reasons: it was the first land defeat of the Japanese Imperial Army; it marked the start of the great roll-back of the Japanese troops from the southernmost point of the Pacific empire; and it was the battle that saved Australia from certain isolationand possible invasion, as it was perceived at the timein the Pacific War.

Against this backdrop, the heated argument over the correct name of the jungle path along which the Australians and the Japanese fought seems trivial. To my mind, a track is little different from a trail or path, and I have used these terms interchangeably. Where I formally identify it, I use Kokoda Track, because that is the preferred name of the Isurava Memorial and most soldiers. Incidentally, a research paper by Peter Provis on the subject, commissioned by the Australian War Memorial, concludes that Trail is technically correct, but concedes that either may be usedfor which clarity one is, I suppose, thankful.

Landing

Missionaries

Dry your tears. Perhaps they are otao naso, our friends

Father James Benson to a Papuan boy, on seeing the Japanese ships

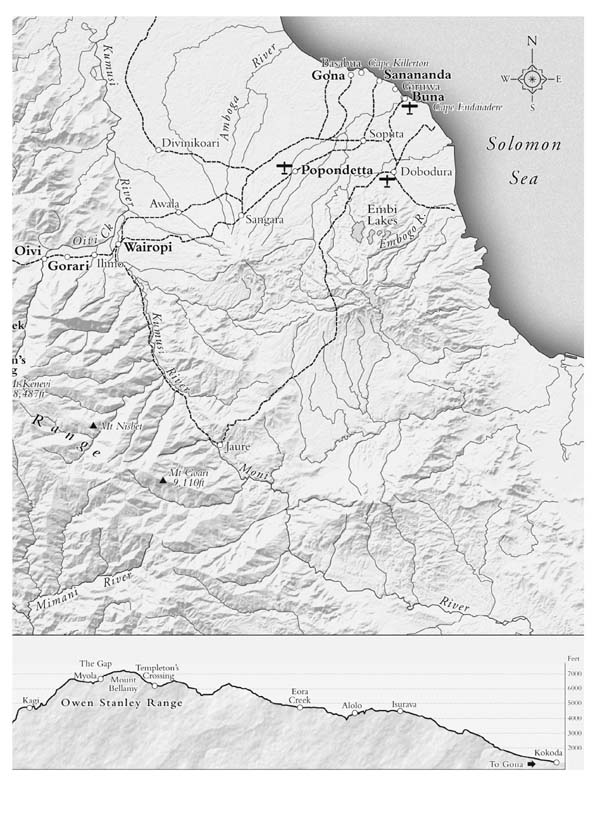

O n the afternoon of 21 July 1942, a humble Christian missionary was fixing his deckchair in his shed by the Solomon Sea. Father James Benson enjoyed pottering about with his tools at Gona Mission, on the north coast of Papua. The little deckchair served a special function for this Yorkshire-born clergyman: he would perch himself upon it aboard the native outriggers that plied his coastal parish.

Benson, the Anglican missionary at Gona since 1937, was a respected local figure. Hed devoted himself to the spiritual wellbeing of his small flock, many of whose ancestors were head-hunters; and while not every Papuan had converted to Christianity as enthusiastically as he might have hoped, Benson could not complain. His parish numbered several hundred, and those parishioners who had not gone bush were models of zealous attentiveness.

Two decades earlier their tribes had been warriors and cannibals who solved tribal disputes with bloodshed, and whose trophies of war were the shrivelled heads of their real or imagined enemies. They were the Orokaiva and Binandere people, with a reputation for being bellicose in the extreme as he also observed.

The flaxen-haired Orokaivans, whose oiled ringlets grew into a mass of tails, pencil-thick, and fell about their shoulders in the manner of a Chief Justices wig

Yet in time these powerfully built people adapted to white rule, and agreeably sheathed their scalping knives to participate in the less dangerous diversions introduced by the colonial power: chiefly cricket and football. Western controls were introduced. The Orokaivans who joined the local constabulary gained a reputation for cheerful bravery, transmuting the ferocious warrior ethos of 1920 into a force for order and relative stability. Notwithstanding Governor Murrays appeal for less Christ and more cricket, some eschewed sorcery for Christianity and, in 1942, some three hundred parishioners welcomed the familiar sight of their white-haired preacher who, sitting up in his outrigger, came by sea to spread the word of the white mans god.

At about 4.00 p.m. that day, Benson heard loud cries from Gona beach. An assistant ran up to the door of his shed: Father! Great ships are here! He stored his deckchair and packed some odd items in a canvas satchel: a cheap watch, a few sticks of tobacco, a notebook and pencil, some spare handkerchiefs and a compass. He then walked the few hundred yards from his mission compound down to the grey, palm-shaded sands of Gona beach. A tearful little Papuan boy stood there, crying and shaking with terror, and pointing at the great black ships that loomed offshore.

The Japanese fleet had penetrated the network of shallow tropical reefs and was almost on the beach.Maclaren King. But the monsters anchored off Basabua Point, their hulls shimmering in the afternoon sun, were from another world.

Dry your tears, said Benson. Perhaps they are otao nasoour friends. The reverend instructed the boy to rejoin his people at Jenat, some two miles up the beach, and went to confer with the senior Papuan teacher and the missions two young Anglican Sisters: Miss May Hayman and Miss Mavis Parkinson.

Benson had been alert to the Japanese threat since December 1941. That month the Australian Government recommended the compulsory evacuation from Darwin, Papua and New Guinea of all women and children other than missionaries who may wish to remain and nurses.

New Guinea was a colony of Australia, which had been granted a mandate over the northern region, New Guinea, and the nearby islands, at Prime Minister Billy Hughes behest during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Papua and New Guinea would form ramparts to be held from the hands of an actual or potential enemy. Only 1500 white people lived in Papua, the southern half of the island, and 4500 in New Guinea, in 1939. The local people numbered around 1.8 million, representing a huge variety of ethnic and language groups for whom extreme violence tended to be the chief mode of dispute settlement until European guns, the rule of law and the church (chiefly the Seventh-Day Adventists) arrived to pacify them in the early twentieth century.

Most white civilians had left Papua by July 1942. At Gona, Benson and the two young women elected to stay. Mavis Parkinson, a teacher who ran the three schools in Gona, got permission from her parents back in Ipswich, Queensland, to remain. Elsewhere in Papua and New Guinea, 689 foreigners, including 121 missionaries with 26 children, decided similarly against evacuation, and remained in their villages.

Benson was under no illusions about Japans intentions. Hed seen hundreds of refugees fleeing the Japanese attacks on Salamaua and Lae pulling up on the beach; hed witnessed the occasional dogfight in the sky. He prevailed upon the two young women to leave Gona, but they refused. They bossed him about in a cheerful way, and were unyielding in their determination.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Kokoda»

Look at similar books to Kokoda. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Kokoda and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.