About the Book

MARCH 1945

A handful of young Allied operatives are parachuted into the remote jungled heart of the Japanese-occupied island of Borneo, east of Singapore, there to recruit the islands indigenous Dayak peoples to fight the Japanese. Yet most have barely encountered Asian or indigenous people before, speak next to no Borneo languages, and know little about Dayaks other than that they have been and may still be headhunters. They fear that on arrival the Dayaks will kill them or hand them over to the Japanese. For their part, some Dayaks have never before seen a white face.

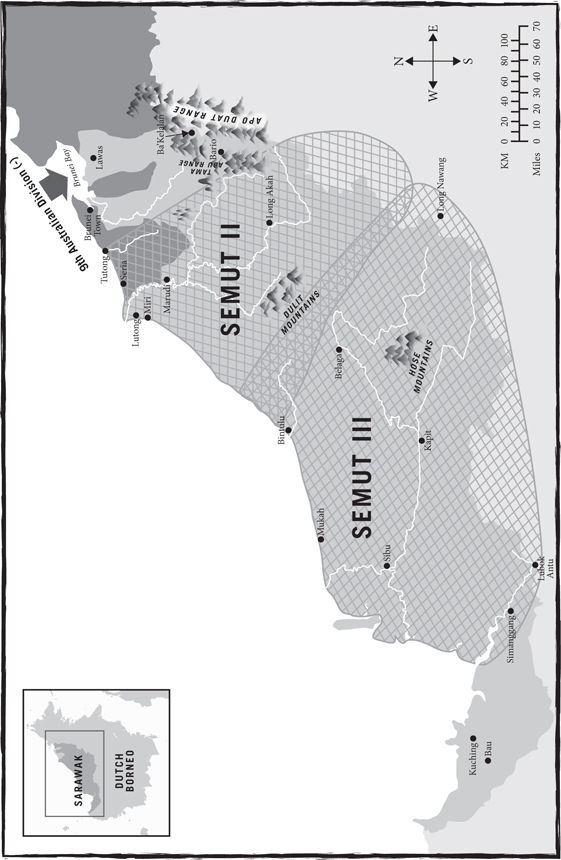

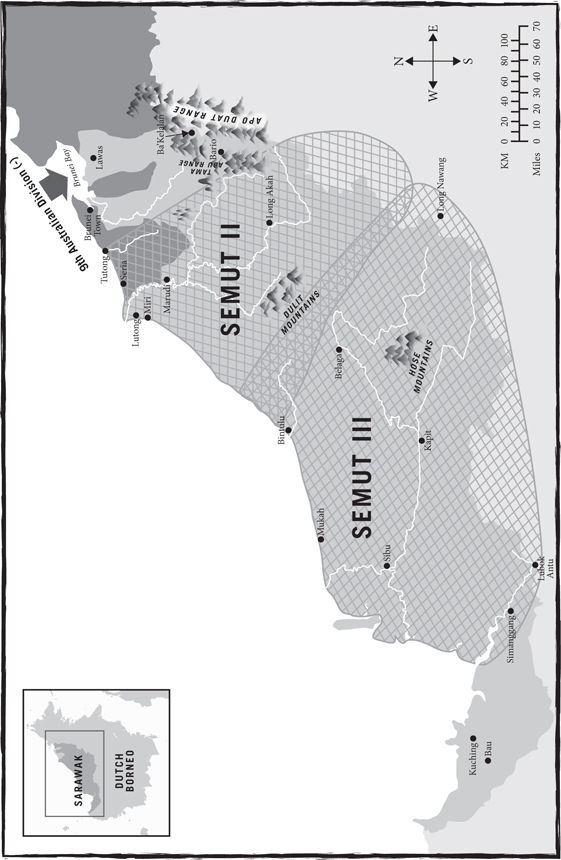

So begins the story of Operation Semut, an Australian secret operation launched by the shadowy organisation codenamed Services Reconnaissance Department popularly known as Z Special Unit in the final months of WWII. Anthropologist Christine Helliwell has called on her years of first-hand knowledge of Borneo, interviewed more than one hundred Dayak people and all the remaining Semut operatives, and consulted thousands of military and other documents to piece together this astonishing story. Focusing on the operations activities along two of Borneos great rivers the Baram and Rejang this book provides a detailed military history of Semut IIs and Semut IIIs brutal guerrilla campaign against the Japanese, and reveals the decisive but long-overlooked Dayak role in the operation.

But this is no ordinary history. Helliwell captures vividly the sounds, smells and tastes of the jungles into which the operatives are plunged, an environment so terrifying that many are unsure whether jungle or Japanese is the greater enemy. And she takes us into the lives and cavernous longhouses of the Dayaks, on whom their survival depends. The result is a truly unique account of the encounter between two very different cultures amidst the savagery of the Pacific War.

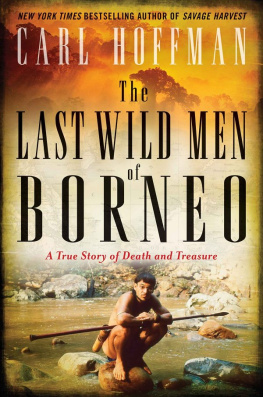

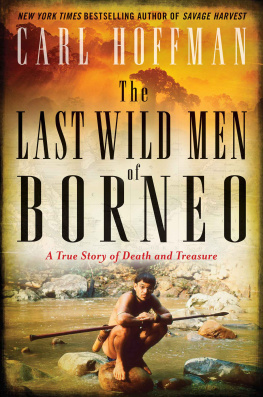

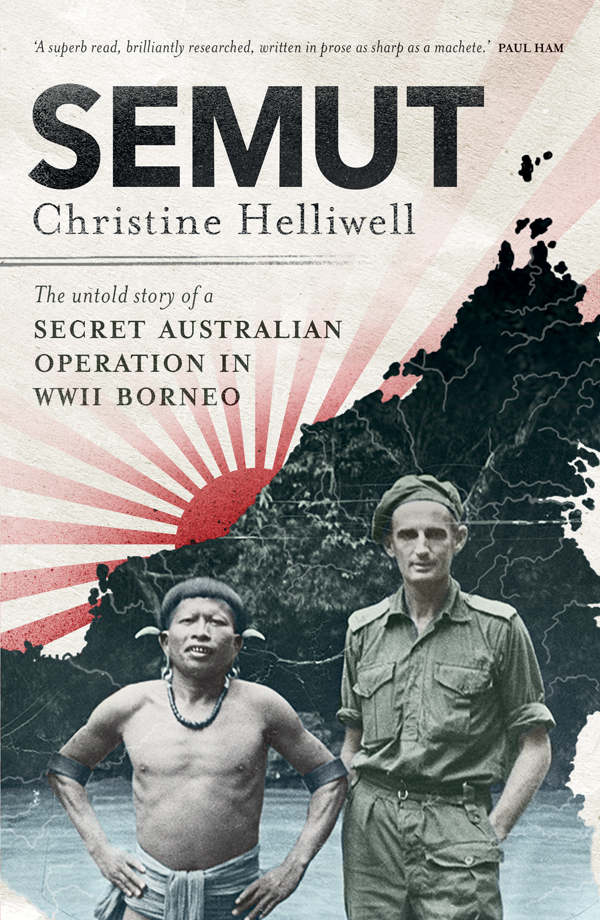

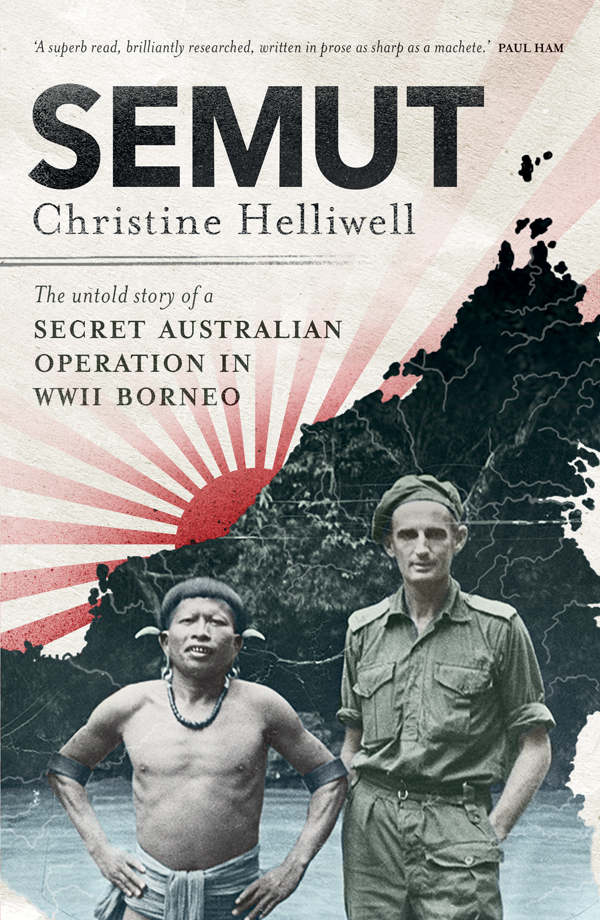

Kelabit chief Dita Bala is pictured on the front cover with Operation Semut leader Major Toby Carter at Long Datih on the Tutoh River, Sarawak, around 23 April 1945. Dita Bala is wearing the teeth of a clouded leopard in his ears and a string of ancient glass beads around his neck, both indicating his high status.

For the operatives of Semut

and the many Dayaks who worked and fought beside them

And for

Jack Tredrea (19202018)

Barry Hindess (19392018)

Going up that river was like travelling back to the earliest beginnings of the world, when vegetation rioted on the earth and the big trees were kings.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

The Dayaks were our saviours, really.

Bob Long, Operation Semut veteran, September 2014

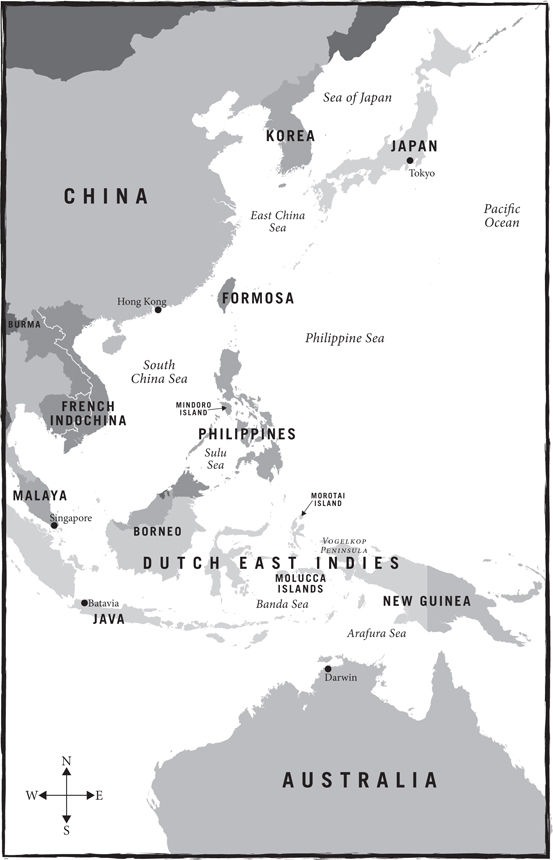

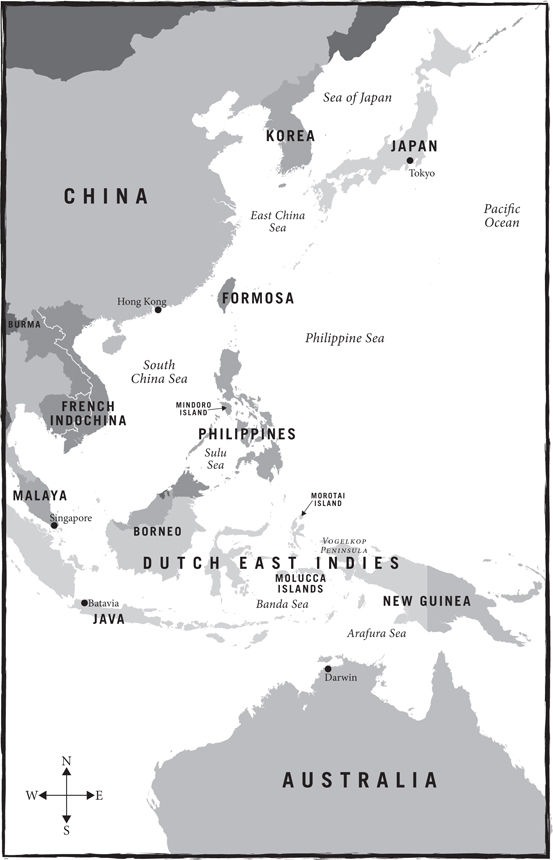

Eastern Asia and the western Pacific Ocean immediately prior to WWII.

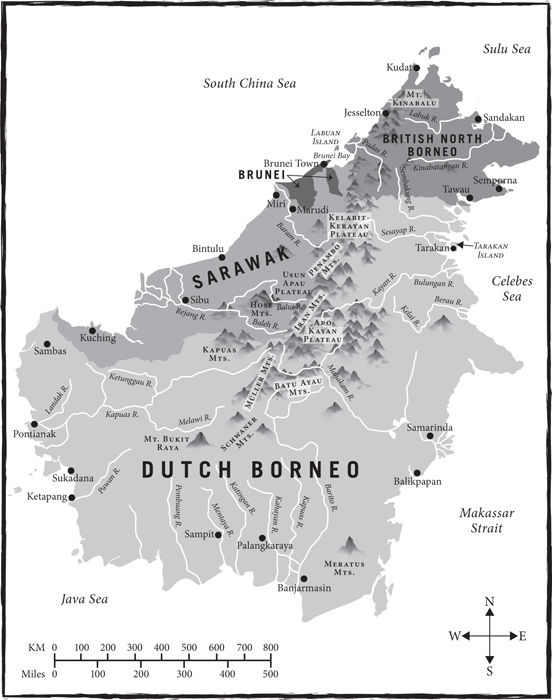

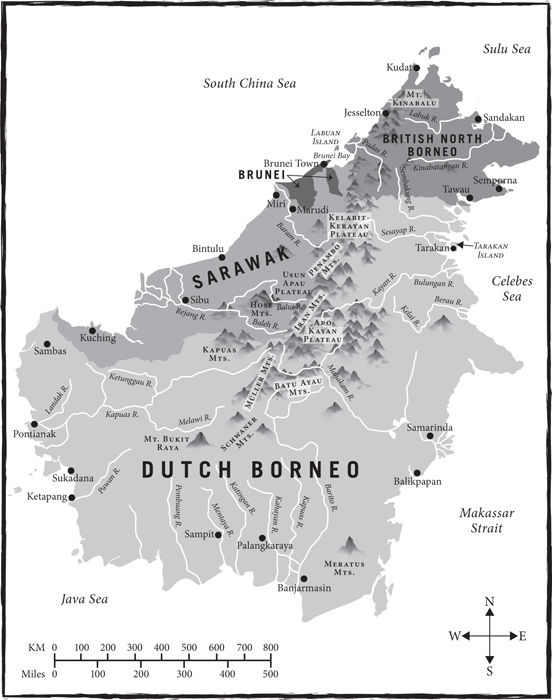

Borneo immediately prior to the Japanese occupation.

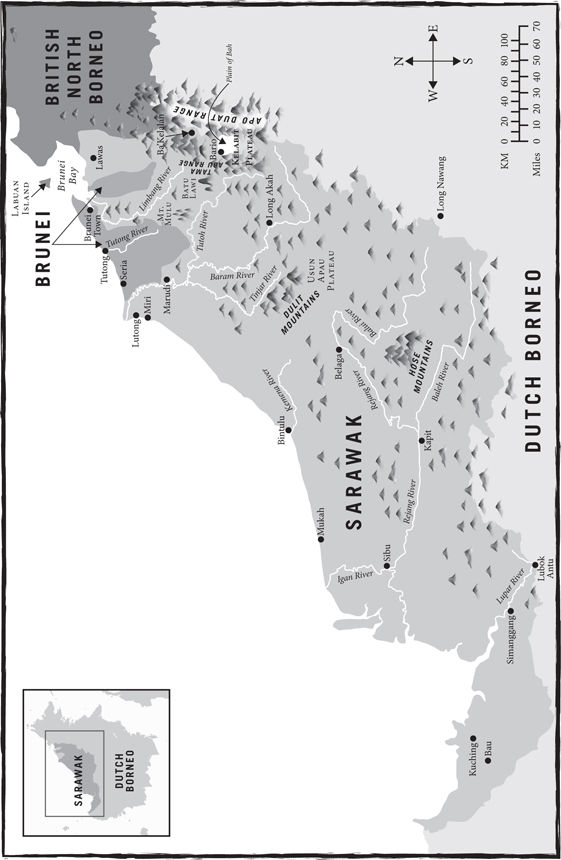

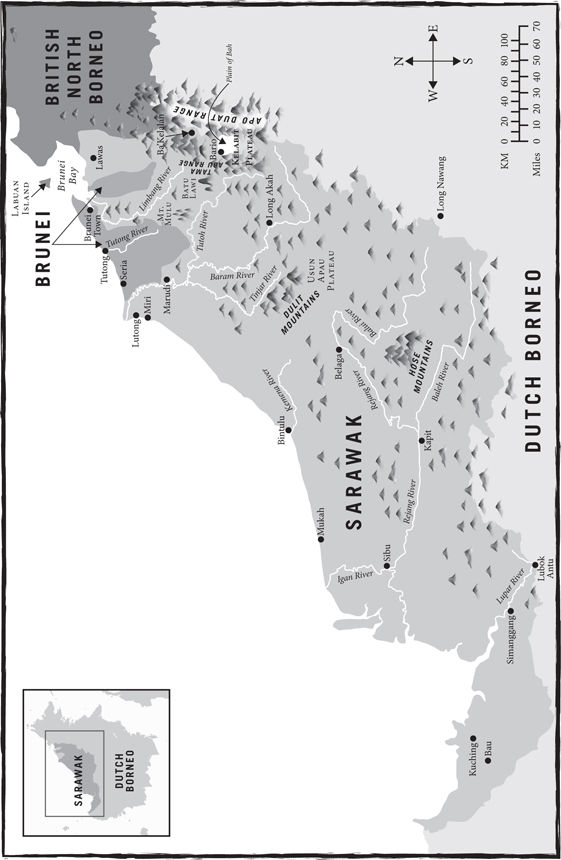

Sarawak immediately prior to the Japanese occupation.

Sarawak showing Semut II and Semut III approximate operational areas.

PREFACE

An old man, his arm around a woman, smiles from a photograph at the top of my computer screen. His thin white hair and neat cardigan somehow speak of his lifelong vocation as a tailor: a gentle profession also reflected in the shyness of his gaze. However, in 1945 this man, then aged just twenty-four, led a troop of local Dayak tribesmen through Borneos jungles in a secret war against the Japanese. His name is Jack Tredrea and in the photo he is ninety-four years old. And the woman he is hugging is me.

I first met Jack in 2014 when I visited his home in Adelaide to interview him after learning he had taken part in a World War II (hereafter WWII) Allied special operation in Borneo. Although I had been carrying out research on WWII in Borneo for some time, Jack was the first Allied soldier I interviewed. I flew to Adelaide in September of that year, accompanied by a videographer from the Australian War Memorial (AWM). I was thrilled to be meeting someone who had travelled through Borneos astonishing jungles in the 1940s, long before the terrible destruction inflicted on them in later years by rampant logging and the establishment of vast palm oil plantations. I had first gone to Borneo in the 1980s forty years after Jack as a young woman looking to conduct research for a PhD in anthropology, and had lived for twenty months in a longhouse in the jungle, studying the social and cultural life of its Dayak inhabitants. Like Jack it had been my first time outside Australasia. I have spent a lot of time on the island in the years since, but never forgotten my first few months there.

As we settled down in Jacks immaculate living room under the eye of the video camera and his family photos, I asked him about the Borneo jungle. I thought, he said, that it was the most beautiful place on earth. And so began our friendship, forged over a shared love for a tragically disappearing place.

In early 2016 Jack and I joined forces to lobby the AWM to install a plaque on its grounds honouring Z Special Unit, the name by which Jack knew the Australian secret military organisation with which he had fought during WWII. Like all Z Special Unit personnel, he had signed secrecy provisions, and during his postwar debriefing he was ordered to remain silent for the next thirty years about his activities with the organisation. Other, although by no means all, Z Special men received similar orders some even being sworn to secrecy for life. Many obeyed and, as a result, in large parts of Australia there were no Z Special Unit veterans associations until the 1970s; in the absence of a Z Special banner, Jack marched with the 1st Australian Parachute Battalion each Anzac Day. The organisations lack of visibility meant that it was one of very few from WWII never to have been honoured with a dedicated plaque at the Memorial.

Memorial approval for the plaque was quickly received and I began a search throughout Australia and overseas for Z Special personnel and their families, hoping that many would travel to Canberra for the dedication ceremony. This was a crazily ambitious undertaking since the organisations recruits had come from several countries and few up-to-date contact details were available. In addition, those who remained would now be very elderly and likely to find travel difficult. But finally on 1 August 2016, after seventy years of waiting, more than twenty aged veterans and around one thousand family members gathered opposite the AWM sculpture garden (a group even having crossed the Tasman Sea from New Zealand) to honour and remember. Many of those who attended had lost husbands, fathers, grandfathers, brothers, uncles and friends to the organisations notoriously perilous operations, and had made the trip to lay their grief to rest. As the Ode was read and the melancholy strains of the Last Post sounded across the Memorials sweeping lawns under a sombre winter sky, it was impossible not to weep.