PENGUIN BOOKS

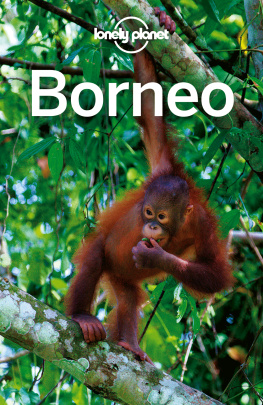

INTO THE HEART OF BORNEO

Redmond O'Hanlon is an explorer in the nineteenth-century mould. In addition to his bestselling travel books, Into the Heart of Borneo, In Trouble Again, Congo Journey and Trawler, he has published scholarly works on nineteenth-century science and literature. For fifteen years he was the natural history editor of The Times Literary Supplement. He lives outside Oxford with his wife and two children.

Redmond O'Hanlon

INTO THE HEART OF BORNEO

An account of a journey made in 1983 to the mountains of Batu Tiban with James Fenton

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, NewYork, NewYork 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen's Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, II Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi -110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), cnr Airborne and Rosedale Roads, Albany, Auckland 1310, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published by The Salamander Press Edinburgh Ltd 1984

Published in Penguin Books 1985

Copyright Redmond O'Hanlon, 1984

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN:978-0-14-193590-4

To my wife, Belinda

The author wishes to thank 22 SAS; Eric Jacobs and the Sunday Times; Bill Buford and Granta; Galen Strawson; Ernst Mayr; Max Peterson; Linda Hopkins; and Fuji Cameras (UK) Ltd.

ILLUSTRATIONS

After the march

ONE

The situation in Sarawak as seen by Haddon in 1888 is still much the same today. He found a series of racial strata moving downwards in society and backwards in time as he moved inwards on the island.

C. D. Darlington, The Evolution of Man and Society, 1969

As a former academic and a natural history book reviewer I was astonished to discover, on being threatened with a two-month exile to the primary jungles of Borneo, just how fast a man can read.

Powerful as your scholarly instincts may be, there is no matching the strength of that irrational desire to find a means of keeping your head upon your shoulders; of retaining your frontal appendage in its accustomed place; of barring 1,700 different species of parasitic worm from your bloodstream and Wagler's pit viper from just about anywhere; of removing small, black, wild-boar ticks from your crutch with minimum discomfort (you do it with Sellotape); of declining to wear a globulating necklace of leeches all day long; of sidestepping amoebic and bacillary dysentery, yellow and blackwater and dengue fevers, malaria, cholera, typhoid, rabies, hepatitis, tuberculosis and the crocodile (thumbs in its eyes, if you have time, they say).

A rubber suit, with a pair of steel waders, seemed the obvious answer. But then the temperature runs to 95F in the shade, and the humidity is 98 per cent. Hose and McDougall's great two-volume masterpiece The Pagan Tribes of Borneo (1912), Alfred Russel Wallace's The Malay Archipelago: the Land of the Orang-Utan and the Bird of Paradise (2 vols, 1869; a book even richer than its title indicates), Odoardo Beccari's Wanderings in the Great Forests of Borneo (1904), Hose's The Field-book of a Jungle-Wallah (1929) and Robert Shelford's A Naturalist in Borneo (1916) offered no immediate solution. And then meek, dead, outwardly unimpressive, be-suited and bowler-hatted Uncle Eggy came to my rescue.

Reading Tom Harrisson's memoirs of the war against the Japanese in Borneo, World Within (1959), I came across the following passage. Harrisson, sent out of his own unit on a secret mission, faces his selector:

In the relics of a Northumberland Avenue hotel, I was interviewed by Colonel Egerton-Mott Mott offered me Borneo adding that I was about the last of their hopes. They had already (he said) asked everyone with any conceivable knowledge of the country, including my colleagues of the 1932 Oxford expedition. When I practically leapt at the offer, he shed his cavalry veneer of calm for a second in pleased evident relief. For, in a tiny way, the British services at that moment badly needed to find a few men to go back into Borneo and try to save some of the face, chin-up, lost to the Japanese.

For the next few weeks my lately softening feet hardly felt ground. Special Operations Executive, SOE, the British centre of cloak-and-dagger, was a most efficient organisation, in a different class from the ordinary army or civilian services. Parachuting, coding, disguise, hiding, searching, tailing, burglaring, stealing trains, blowing up railway bridges, shamming deafness, passing on syphilis, resisting pain, firing from the hip, forgery and the interruption of mail, were some things one could learn in intense concentration. None of them would be of much use in the east. But the acquisition of so much criminal and lethal knowledge gave a kick of self-confidence.

So now, at last, I knew how my mild-mannered uncle had really spent his time, the nature of that something in the City and those interests in the East of which my aunt would speak with such disdain. Armed with my newly-revealed ancestor, I decided to seek help from the intellectual descendants of the Special Operations Executive.

The training area of 22 SAS near Hereford is the best place on earth from which to begin a journey upriver into the heart of the jungle. The nearest I had ever come to a tropical rain-forest, after all, was in the Bodleian Library, via the pages of the great nineteenth-century traveller-naturalists, Humboldt, Darwin, Wallace, Bates, Thomas Beltand, in practice, a childhood spent rabbiting in the Wiltshire woods. My companion James Fenton, however, whose idea the venture was, enigmatic, balding, an ex-correspondent of the war in Vietnam and Cambodia, a jungle in himself, was a wise old man in these matters.

Still, as the gates swung open from a remote control point in the guardroom and our camouflaged Land Rover climbed the small track across the fields, even James was unnerved by the view. Booby-trapped lorries and burnt-out vehicles littered the landscape; displaced lines of turf disclosed wires running in all directions; from Neolithic-seeming earthworks, there came the muffled hammering of silenced small-arms fire; impossibly burly hippies in Levi jeans and trendy sweaters piled out of a truck like fragments of a hand-grenade and disappeared into the grass; mock-up streets and shuttered embassies went past, and then, as we drove round a fold in the hill, an airliner appeared, sitting neatly in a field of wheat.

What's that? said James.

Malcolm and Eddy forebore to reply.

We drew up by a fearsome assault course (the parallel bars you are supposed to scramble over with enthusiasm reared into the sky like a dockside crane) and made our way into the local SAS jungle. Apart from the high wire perimeter fence, the frequency with which Land Rovers drove past, the number of helicopters overhead and the speed with which persons unknown were discharging revolvers from a place whose exact position it was impossible to ascertain, it might have been a wood in England.

Next page