Hoffman - The Last Wild Men of Borneo

Here you can read online Hoffman - The Last Wild Men of Borneo full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2018;2014, publisher: HarperCollinsPublishers, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Last Wild Men of Borneo

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollinsPublishers

- Genre:

- Year:2018;2014

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Last Wild Men of Borneo: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Last Wild Men of Borneo" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Last Wild Men of Borneo — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Last Wild Men of Borneo" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

For Max

Natures first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leafs a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

ROBERT FROST

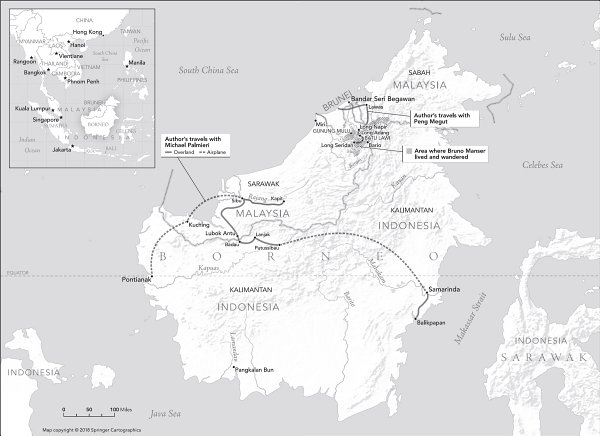

This is a work of nonfiction reconstructed through thousands of pages of original, contemporaneous journals, letters, news articles, films, still photographs; hours of in-person interviews in Indonesia, Malaysia, Switzerland, France, Austria, and Canada; telephone interviews; and two monthlong trips to Malaysian Sarawak and Indonesian Kalimantan, where I walked in many of the very same footsteps traveled by the characters in this story. There are a few tales here, however, that feel so wild they defy belief, with no corroborating witnesses or documents. I think theyre true, but only the tellers know for sure.

Dayak in full war regalia: hornbill feathers, shield, blowpipe, leopardskin vest, and head-hunting sword. (Collection Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen. Coll.no. TM-60033041)

to the heart of America via the Internet. College football. The USC Trojans versus the Arizona Wildcats. He loved the Trojans. But the sound was off. And as he registered this, he heard them again: footsteps. Upstairs. Pacing and stomping.

He jumped up, wrapped himself in a sarong, and quietly pushed open the ornately carved double doors to the living room. On the outside of the door hung a mask, all big eyes and gaping mouth and a long green tongue, with braids of black hair dangling animal teeth and shells and odd seeds, a guardian protecting the inner sanctum of his bedroom. The house flowed into a small garden, like many buildings on the island, and maybe someone had climbed over the garden wall and into his home.

He flicked on a light switch. There was a lot to steal: aged gongs dangling from coppery brown eaves; glass-fronted cases full of brass Buddhas; amber earplugs; traditional head-hunting swords with elaborately carved bone handles in equally decorated scabbards. The wall opposite the garden resembled a display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a four-foot-tall piece of two-hundred-year-old wood, carved in swirling, stylized branches, reigned as the centerpiece, but around it hung masks with hornbill feathers and haunting mirror eyes and an old wooden ritual vessel in the shape of a canoe, its prow carved in the likeness of a hornbill head, the sacred bird of the island of Borneo. On a stand stood an old shield bearing the same motif of intertwining branches and big watching eyes and fangs, and on his desk lay a bamboo quiver holding poison arrows, its handle carved in the shape of a crocodile.

Bang. Crash. More footsteps.

Michael turned left and headed up the stairs.

O n the night Michael told me this story, he looked nearly identical to the septuagenarian actor Jack Nicholson. The same hair, the same complexion, the same facial structure and smile; more than once I watched as women, from out of nowhere, slid their arms around his big shoulders and lifted their phones as he leaned into them and cracked a smile while they took a photo, all without speaking.

Do you know her? I asked the first time it happened.

No! he said. They think Im Jack Nicholson. I go with it.

He was seventy-two years old, stood five foot ten inches, had gained some girth, but still emanated vitality, a former surfer with a gray soul patch below his lower collections of millionaires in the worlds greatest cities. Bali had long been the epicenter of Oceanic tribal art, with prices for the best pieces now hitting seven figures, a nexus of dealers and collectors with tentacles reaching Western wealth and culture in Paris, New York, Brussels, San Francisco, Genevaand Michael had brought out many of its masterpieces.

To the thousands of Americans and Europeans pacing the streets of Ubud, the islands longtime artistic capital, yoga mats dangling from their shoulders in search of spiritual sustenance, the mystical energy of Bali had been discovered through Elizabeth Gilberts mega bestseller Eat Pray Love (or through Julia Roberts playing Liz Gilbert in the film version). But westerners had been drawn to Bali since the 1920s and 1930s, and Michael had been here since the early 1970s. He and his friends had streamed to the island to the east of Java in the Indonesian archipelago in search of freedom, art, passionparadise. The exotic, the transcendent, the white-sand beaches, the blue-green surf that stretched for miles.

Not to mention the cheap living, an Eden of palm trees and terraced rice paddies threaded by dirt roads and dotted with Hindu temples, the heady scents of clove cigarettes and incense drifting up to the Balinese gods. They were hippies then, gypsies escaping from conventional livesand the draftback home, wherever home was. Some had family money, the rest hustled, though it didnt take much in those days. Marijuana, for many. Crafts and jewelry and funky tropical clothing for others. And for a few with good eyes and good taste, it had been art from Indonesias thousands of islands, many still unexplored oases of traditional cultures and old ways. Theyd informally divided up the land into exclusive zones: Alexander (Axel) Goetz took Java. Perry Kesner claimed Sumba. And Borneo was Michaels.

Forty years later they were still here, even though the Balinese paradise often appeared sullied now, Heavy, shiny, thick, inlaid with a ruby and two emeralds. Nine hundred years old. Later I would discover that he always wore a heavy antique gold ring, and it was always a different one.

Across from me at the table was Perry Kesner. He had a shaved head, a gray mustache, heavy eyebrows, a thick New York accent, a muscular body despite his sixty-two years. He wore a deep V-necked tie-dyed T-shirt. and her mothers Upper East Side gallerys clients over a fifty-year period were Jacqueline Kennedy, John D. Rockefeller III, the Met, and the National Gallery of Australia, which paid $1.08 million for a stolen Buddha it bought from Wiener in 2007.

I had no indication that Michael or Perry or Axel were involved in anything illegal, but these post-surfer-hippies around me were among the biggest players in Indonesian art; this was the red-hot center of the business, the real business that you didnt see when you stood before a beautiful piece in the Yale art museum or in a Paris gallery. They held no university degrees, didnt pop up on society pages. But if you owned a piece of Indonesian art, or admired one in a museum, there was a good chance it had come via one of them. They were buccaneers hiding in plain sight. And in certain placesthe streets of Saint-Germain-des-Prs in Paris, the back rooms of museums and auction houses from Switzerland to San Franciscothey were famous, legendary, sometimes controversial. None more than Michael.

Meeting him had been pure serendipity. I had long been fascinated by the persistent Western obsession with remote tribal people, my own included, in 1991and to the Penan themselves, not to mention enemy number one of the Malaysian government.

His behavior, though, became ever more reckless, obsessive even. Then, in 2000, he vanished. Poof. Gone without a trace. Rumors abounded. That hed been murdered by the Malaysian government. That hed gone native

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Last Wild Men of Borneo»

Look at similar books to The Last Wild Men of Borneo. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Last Wild Men of Borneo and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.