Table of Contents

For Katja

PREFACE

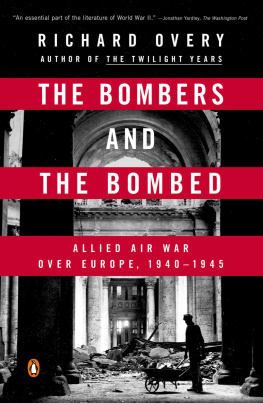

On Feb 2, 1945, James (Jimmy) Doolittle, famous for the retaliatory raids on Tokyo following Pearl Harbor, was awaiting orders. He had been told by his superior, Carl Spaatz, to launch a bombing raid on the heavily populated center of Berlin. For Doolittle, it was a betrayal of the principles to which America had committed itself since the United States entry into the war: bombing would be precise, would hit industry, and would avoid civilian casualties. We will, Doolittle had written, in what may be one of our last and best remembered operationsviolate the basic American principle of precision bombing of targets of strictly military significance.... When Doolittle received his reply, it was unequivocal: hit Berlincenter of [the] city.

Decades later, near the end of his life, Spaatz looked back on the early February 1945 bombing of the German capital with regret. We never had as our target in Europe anything except a military targetexcept Berlin.

The debate between Doolittle and Spaatz, and between Spaatz and his own conscience, fit into a larger debate that raged throughout the Second World War: how to bomb Nazi Germany. From the moment the war started, airmen on both sides of the Atlantic were convinced that airpower would play a central role in defeating the enemy. Until 1944, it was the only way in which the Allies brought the war directly to Germany. And until the end of the war, the Allies could not agree on bombing strategy. In this context, the exchange between Doolittle and Spaatz is remarkable. It is remarkable for Doolittles passion, for his willingness to challenge a superior officer (though also a friend), but also for the result, which was a deviation from American policy. For the majority of the war, the Americans remained publicly committed to the precision bombing of noncivilian targets; their British Allies, by contrast, were committed (from 1942) to the carpet bombing of heavily populated cities.

The American commitment to precision made the American bombing campaign over Europe unique. This important point has been forgotten. In recent years, there has been a great effort, particularly but not only among authors publishing with commercial presses, to downplay if not trivialize the differences between the American and British campaigns. Those holding this view argue that poor weather, German defenses, and often imprecise radar technology meant that while Americans were trying to hit precise targets they were hitting much else, civilians included. This is all true. But it is also true that intention matters: unlike their British Allies, American airmen were, with some important exceptions, committed to the precision bombing of noncivilian targets until the end of the war. At times, they maintained this commitment at very great cost to themselves. As another airman put it, It is contrary to ideals to wage war against civilians. There is an important and basic difference, often lost to contemporary moralizers discussing Iraq, Afghanistan, or Lebanon, between killing civilians incidentally and killing them deliberately.

The failure to distinguish sufficiently the two bombing campaigns has, this book argues, encouraged a misunderstanding of the role of bombing in ending the war. Authors keen to defend British Bomber Command against the charge that carpet bombing cities was immoral and pointless tend to exaggerate these effects, suggesting that bombing in general and city bombing in particular played a decisive effect in defeating Germany. This view is very hard to credit; on any reading, bombing was just one part of the war, and the role it played has to be considered in the context of contributions made by the Western Armies and Navies in the other theaters of war, and of course by the Soviet Union. That said, it is also a mistake to suggest, as many critics have, that Allied bombing had no effect on the outcome of the war. It did. The question is rather what effect, which type of bombing, and whether the results constituted the wisest use of scarce military resources. On this point, the distinction between the American and British campaigns is relevant. Bearing in mind that determining cause and effect is always very difficult, the evidence, as this book shows, suggests that the bombing that damaged Germany the mostthe destruction of industrial targets and the inestimably important obliteration of the German fighter forcewas done by the Americans. At three points in the bombing campaignin 1943 (twice) and in late 1944/early 1945American precision bombing almost brought the Germans to their knees. Compared with the British, the Americans bombed better, with greater results and lower loss of life, both civilian and military.

Bombing debates were about more than strategy; they were also about morality. This was the case both during the war and after. To the end, the American campaign was affected by a particular concern for the moral implications of bombing. Many writers today deny this, and Spaatz and Doolittle were keen after the war to disassociate themselves from the taint of morality. It is clear why: expressing concerns over women and children was at best unstrategic; at worst, it was unmanly. It is nonetheless impossible to read the exchange above, or other passionate denunciations of area bombing discussed in this book, without seeing a deep and abiding moral concern.

For their part, the RAF led a campaign that was, from 1942, committed, daring, and produced at times spectacular results. In the end, however, the British obsession with the obliteration of German cities (the Commander-in-Chief of Bomber Command, Sir Arthur Harris, promised to take them out one after another, like pulling teeth) was ultimately counterproductive. It had few direct effects on German production, which rose unchecked until late in 1944. Area bombings indirect effects (forcing the Germans to transfer resources from other theaters of war to the home front), about which much has been made, could have been achieved at lower cost through precision bombing.

In writing this book, I have relied on a wide range of sourcesarchives, personal interviews, and memoirs of the key characters involved. None of these is entirely without problems, but they are essential to reconstructing the air war through the eyes of those who arranged it, those who executed it, and those who experienced it. Two types of sources are worth commenting on. The first are interviews with German civilians. Some might be rightly suspicious of accounts given by Germans who lived through the Third Reich, viewing them as an effort in self-justification. Here time was fortunately on my side. Most of those Germans who remember the Third Reich were children at the time. These children of war (

Kriegskinder) were old enough to remember the bombings, but too young to have been involved in the politics that led up to the war. Equally important, whatever one thinks of them, these children were there, and their stories aresubject to all the usual qualifications that apply to oral historypart of the historical record. In many cases, they expressed great appreciation that anyone, above all a foreigner, would be interested in their stories. A daughter of one eyewitness, from Essen, wrote me a touching letter:

We read about your project in our daily newspaper this week. My mother, born 1937, decided to go out on a limb and to give your assistant her phone number. Your assistant called her back and had a long talk with her. This was the best thing that could have happened to my mother.