2. Richard Norton and the American

Volunteer Motor-Ambulance Corps

3. A. Piatt Andrew and the American

Ambulance Field Service

8. Some Female Drivers and

Other Noteworthy Volunteers

Foreword

A certain lord, neat, and trimly dressd,

Fresh as a bridegroom; and his chin, new-reapd,

Showed like a stubble-land at harvest home:

He was perfumed like a milliner,

And twixt his finger and his thumb he held

A pouncet-box, which ever and anon

He gave his nose and tookt away again.

And as the soldiers bore dead bodies by,

He called them untaught knaves, unmannerly,

To bring a slovenly, unhandsome corpse

Betwixt the wind and his nobility.

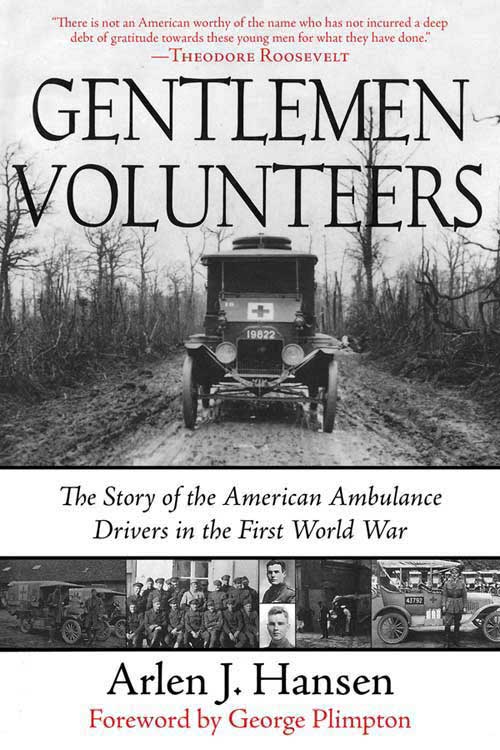

T he above verses (from Hotspurs report to the king after the Battle of Holmedon in Henry IV, Part I) would hardly qualify to describe the noncombatants who drove ambulances in Europe during the Great War, though, in fact, a large number were recruited from New England prep schools and Ivy League universities. These were upper-class gentry perhaps typical of them Richard Norton (the 42-year-old son of Harvards distinguished professor of art history, Charles Eliot Norton), who among other affectations carried not a snuffbox but wore a monocle. He was described by a fellow member of his ambulance section, the writer John Dos Passos, as follows: Dick Norton, aesthete, indomitable archeologist, the man who smuggled half the Ludovici throne out of Italy, a Harvard man of the old nineteenth-century school, snob if you like, but solid granite underneath. Once Norton became actively involved with his ambulance corps he was able to persuade Henry James (who else!) to write laudatory copy about it for the newspapers.

Among Nortons compatriots in the earliest days of the Service were H. Herman Harjes, a 39-year-old partner of the Morgan-Harjes Bank in Paris; A. Piatt Andrew, a 41-year-old Princeton graduate; and Edward Dale Toland, a 28-year-old Main Line Philadelphias who had boarded a steamer in August, 1914, and gone to Europe simply to see the excitement and the French people in wartime (his idea of a vacation !) and, caught up in the real events, stayed on to help form the first American volunteer ambulance unit.

Back home the main recruiter and fund-raiser for Andrewss Field Service was a banker, Henry Sleeper, of the Lee Higginson & Co. in Boston the campuses of the eastern prep schools and colleges his favorite hunting grounds. One might well assume that the best source for manning an ambulance corps would be the garages and repair shops of New England, there to find men schooled in how to make the temperamental machines of that era function. Instead, one would have thought Sleeper was searching out candidates for an extremely exclusive mens club the criteria for membership not the ability to take apart a manifold but good bloodlines and impeccable manners. In his recruiting letter, Richard Nortons brother Eliot insisted that a volunteer must be a man of good disposition possessed of self-control in short, a gentleman.

One is instantly reminded of the recruiting after the Second World War of so-called white shoes undergraduates for service in the Central Intelligence Agency focusing in particular on prep-school graduates who had gone on to Harvard and Yale. It should be noted that the romantic zeal of those picked ultimately led to such disasters as the Bay of Pigs. Better to have amateurs driving ambulances than foreign policy!

There appear to have been three types who joined the ambulance corps: (1) humanitarians (men like Toland and Harjes), (2) pacifists (John Dos Passos, E. E. Cummings), and (3) those itching to get actively involved in the war (Ernest Hemingway, Archibald MacLeish, et al.). By the time the United States entered the war in April, 1917, and the ambulance corps were absorbed by the Red Cross and the U.S. Army, over 3,500 Americans had served in their ranks.

A lot of it had to do, of course, with the romantic idea of warfare in those early days of the conflict so vividly described in such books as Barbara Tuchmans The Guns of August the troops off to the front to the cheers of the crowd, the waving of banners, envied by those either too young or too old to fight. For some, of course, ambulance driving was too tame; they wanted to become more actively involved. Such was the case of James H. McConnell, for whom driving an ambulance wasnt enough. He resigned from the American Field Service and joined the Lafayette Flying Escadrille; soon afterwards he was shot down by the Germans and killed. At the time, he was writing about his service overseas, a posthumously published work titled Flying for France.

The number of those who drove ambulances in Europe and subsequently became famous literary figures is astonishing among them William Slater Brown, Louis Bromfield, Malcolm Cowley, Harry Crosby, E. E. Cummings, John Dos Passos, Julien Green, Ramon Guthrie, Robert Hillyer, Ernest Hemingway, Sidney Howard, John Howard Lawson, Archibald MacLeish, Charles B. Nordhoff (whose reminiscence about the Field Service was called The Fledgling, and who after the war collaborated with James Hall to write the famous sea trilogy about the mutiny aboard the Bounty), William Seabrook, and Edward Weeks, who wrote about his service in the book My Green Age and was subsequently for many years the editor of the Atlantic Monthly. Many of the other writers mentioned incorporated their impressions of the war in their work, most notably John Dos Passos in One Man s Initiations and Three Soldiers, Ernest Hemingway in A Farewell to Arm, and E. E. Cummings in The Enormous Room.

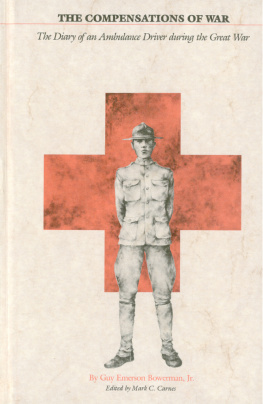

In addition, a number of nonliterary former volunteers wrote books about their experiences indeed so many that some must have worried if they had picked a title already chosen by another. Here are some of them: Leslie Buswells