Copyright 2017 by James McGrath Morris

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Da Capo Press, 53 State Street, Ninth Floor, Boston, MA 02109.

Designed by Jeff Williams

Set in 11.5 point Dante MT by Perseus Books

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Morris, James McGrath author.

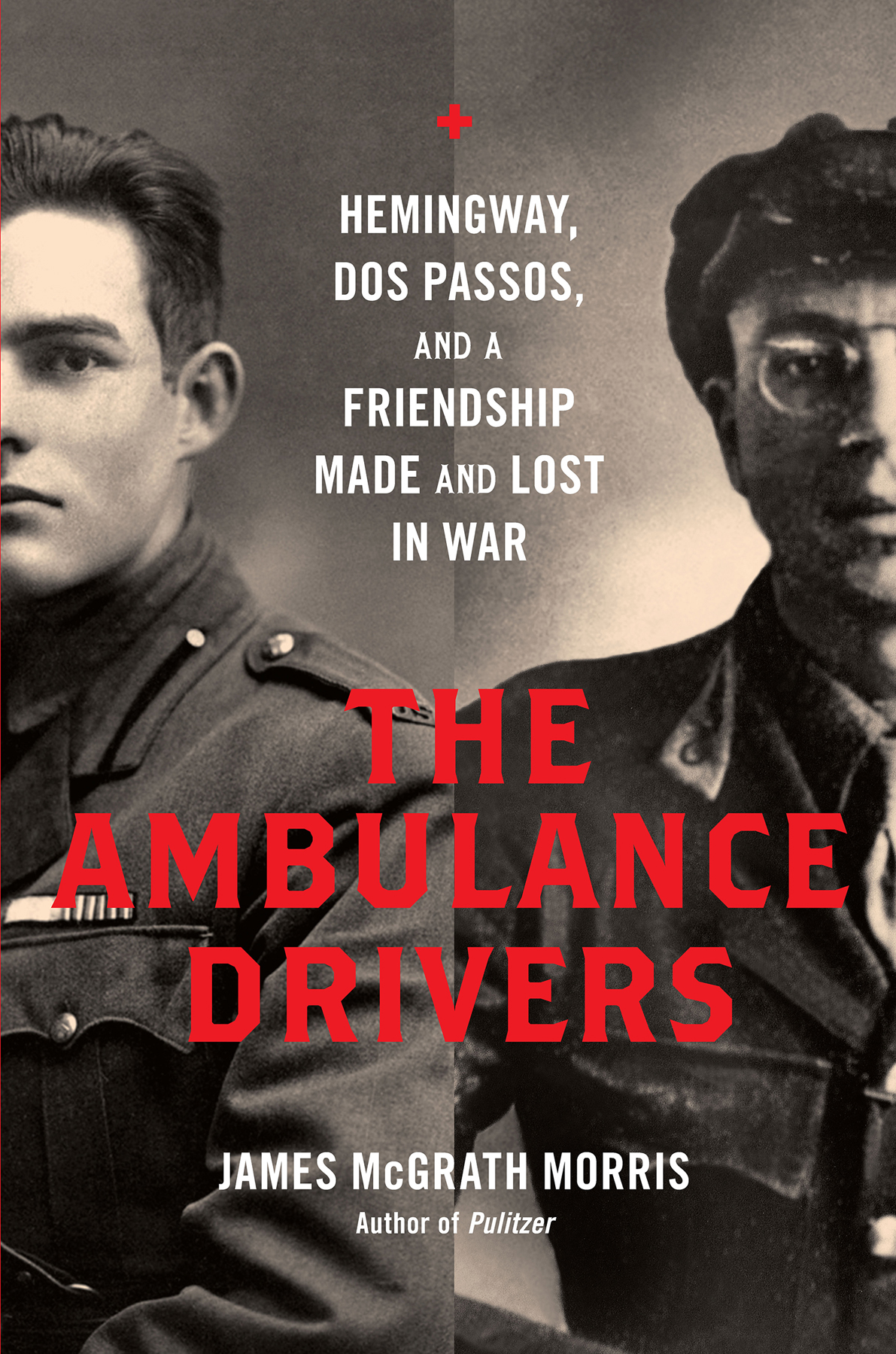

Title: The ambulance drivers : Hemingway, Dos Passos, and a friendship made and lost in war / James McGrath Morris.

Description: Boston : Da Capo Press, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016043398| ISBN 9780306823831 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780306823848 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961Criticism and interpretation. |Dos Passos, John, 18961970Criticism and interpretation. | Hemingway, Ernest, 18991961Friends and associates. | Dos Passos, John, 18961970Friends and associates. | World War, 19141918Literature and the war.

Classification: LCC PS3515.E37 Z74318 2017 | DDC 813/.52dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016043398

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

www.dacapopress.com

Quotations from the works and letters of John Dos Passos used by permission of Lucy Dos Passos Coggin. All rights reserved.

Quotations from unpublished letters by Ernest Hemingway 2017 Printed with the permission of The Ernest Hemingway Foundation.

World rights, excluding United States, Canada, and the Philippines, to quotations from The First Forty-Nine Stories, Hemingway on War, The Sun Also Rises (Fiesta), A Farewell to Arms, and Death in the Afternoon by Ernest Hemingway published by Jonathan Cape, provided by The Random House Group Limited.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at Perseus Books, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special. markets@perseusbooks.com.

E3-20170301-JV-PC

Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, The First Lady of the Black Press

Pulitzer: A Life in Politics, Print, and Power

The Rose Man of Sing Sing: A True Tale of Life, Murder, and Redemption in the Age of Yellow Journalism

Jailhouse Journalism: The Fourth Estate Behind Bars

To our children Stephanie, Benjamin, and Alexander and to our grandchildren.

May they never know war.

In writing you have a certain choice that you do not have in life.

ERNEST HEMINGWAY

Life doesnt often hold out her hand to youI think you should take it when she does and let the consequences take care of themselves, rather than ask if she wears gloves or not.

JOHN DOS PASSOS

IN THE EARLY SUMMER OF 1924 TWO AMERICAN WRITERS SAT IN A PARIS caf. One author came armed with a dictionary, believing that reading the small type would improve his vision. The other brought a King James edition of the Bible. They took turns reading passages aloud from the Old Testament. The Chronicles and Kings were their favorites, along with the Song of Deborah.

The caf where they sat, La Closerie des Lilas, straddled the corner of the boulevard St. Michel and the boulevard du Montparnasse and took its name from the white and purple lilac bushes encircling its terrace. As in most Paris cafs, the garons had become accustomed to delivering caf crme to tables populated by American expatriates swarming the City of Light. As the day wore on, the orders would change to vermouth cassis or the more potent absinthe, a green liqueur that turned milky white when mixed with water.

Of the two men at the table that day, John Dos Passos was the more famous and more accomplished. His last novel had been widely read and much talked about. At this moment he had a multibook contract with a New York publishing house. His straight black hair was already receding at age twenty-eight, giving him a kind of professorial look, which was accented by thick-lensed glasses and the gray suits he favored. When he spoke he did so in a halting .

In contrast, the man sitting across the table from Dos Passos exuded confidence. With a full head of brown lustrous hair, chiseled features, and a broad-shouldered body made taut by vigorous exercise, Ernest Hemingway possessed looks that invariably drew attention, especially from women. But when it came to writing, he was struggling to make ends meet. So far, twenty-five-year-old Hemingway had paid the bills by working as a stringer for a Canadian newspaper and with monthly remittances from his wifes trust fund.

A prestigious annual collection had included one of his stories but misspelled his name. Such was his anonymity. However, a boutique Paris publisher had just printed a slim volume of Hemingways stories and poemswith his name correctly spelled, this timethat brought his literary promise to the attention of American expatriate writers in Paris.

There were a good number of them. The magnetism of Paris made the city irresistible to writers as well as to artists and composers. Popular novelist Fannie Hurst told Washington Post readers in 1924 that Paris was like a beautiful woman. And America, she added, with a sentiment that is .

Paris represented everything their homeland was not for the generation of American writers like Hemingway and Dos Passos who had come of age during the Great War. An incomprehensible number of peoplemore than 17 millionhad been killed, and as many as 20 million had been maimed. It seemed to these young aspiring writers that the United States, which counted only fifty-three thousand combat deaths, refused to recognize that the world was no longer the same and never would be again. In their minds their country obdurately clung to its straitlaced ways, extending its Puritanism to a war on liquor and even to book burning, such as the four hundred copies of the legally banned Ulysses by James Joyce that were condemned to bonfires.

So they fled and came to Paris, described by those who watched as members of a lost generation creating a massive literary party and seeking new forms of expression for the reality of a fractured world. Indeed, to young writers like ourselves, said Malcolm Cowley, who also went to Paris, a long sojourn in France was almost a pilgrimage to Holy Land. By the time Dos Passos and Hemingway sat that summer day at La Closerie des Lilas, Pariss American population had topped thirty thousand. It was not what France gave you, said Gertrude Stein, literary grande dame of the city, but what it did not .

The expatriates created a colony in Montparnasse, the Left Bank quartier of mile Zola and Anatole France. Most of the flats were without running water and many without heat. These American artists wrote in cafs by day, populated clubs at night, drank with abandon, and relished the citys liberated sexual life.

Moneyor, more precisely, its unequal exchangefueled the migration. Foreign currency was the equivalent of being wealthy because the franc was worth so little. American writers, said one expatriate author, flocked to .

Even getting to Paris had become affordable. Steamship companies responding to draconian restrictions on immigration rapidly spruced up and converted their steerage class to Tourist Third Class. Promising a romantic crossing with a bohemian touch, the liners advertised these tickets to .