To Dean M. Sagar

Dont tell stories about me.

Keep them until I am dead.

JOSEPH PULITZER (18471911)

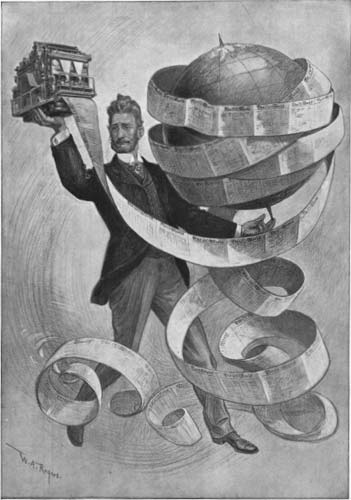

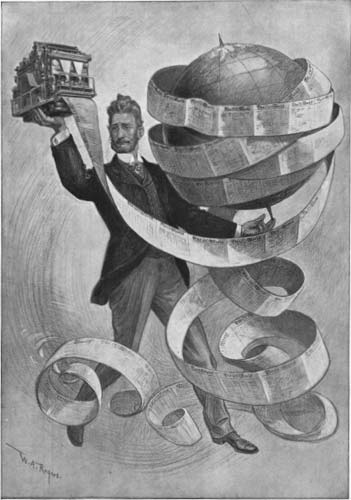

Frontispiece illustration by William A. Rogers was originally published in Harpers Weekly , December 29, 1901.

L ike Alfred Nobel, Joseph Pulitzer is better known today for the prize that bears his name than for his contribution to history. This is a shame. In the nineteenth century, when America became an industrial nation and Carnegie provided the steel, Rockefeller the oil, Morgan the money, and Vanderbilt the railroads, Joseph Pulitzer was the midwife to the birth of the modern mass media. What he accomplished was as significant in his time as the creation of television would be in the twentieth century, and it remains deeply relevant in todays information age.

Pulitzers lasting achievement was to transform American journalism into a medium of mass consumption and immense influence. He accomplished this by being the first media lord to recognize the vast social changes that the industrial revolution triggered, and by harnessing all the converging elements of entertainment, technology, business, and demographics. This accomplishment alone would make him worthy of a biography.

His fascinating life, however, makes him an irresistible subject. Ted Turner-like in his innovative abilities, Teddy Roosevelt-like in his power to transform history, and Howard Hughes-like in the reclusive second half of his life as a blind man tormented by sound, Pulitzers tale provides all the elements of a life story that is important, timely, and compelling.

This book benefits from several fortunate and remarkable discoveries of items previously unavailable to other biographers.

Nearly a century ago, it was reported in newspapers that Pulitzers only living brother had written a memoir shortly before committing suicide in 1909. In 2005, I located the manuscript in the custody of his granddaughter in Paris. An extraordinarily talented sculptor of religious figures, the late Muriel Pulitzer had guarded the work all her life after her father failed to get it published as he had hoped. The memoir sheds new light on the Pulitzers childhood in Hungary, their separate journeys to the United States, their rise as American newspaper publishers, and the prickly relationship between them.

Another important source of material was rescued from a trash bin in St. Louis. More than twenty years ago, the contractor Pat Fogarty spotted some wooden cigar boxes in a Dumpster near a building undergoing renovation. He thought they were too nice to be thrown out, so he took them home. When he opened them he discovered they were filled with documents from the 1800s that had once belonged to Joseph Pulitzers St. Louis Post-Dispatch . He put the boxes in his basement for safekeeping, thinking someday he might be able to sell the items.

In 2008, Pat and Leslie Fogarty generously shared the contents with me. The papers turned out to be historically significant. They included the original receipts for Pulitzers purchase of the Dispatch at auction in 1878, the original merger agreement several days later between the Dispatch and the Post , hundreds of canceled checks signed by Pulitzer, and a loan agreement revealing who provided Pulitzer with the money to operate his first newspaper.

Two other noteworthy sets of documents surfaced in St. Louis during my research. Eric P. Newman provided a copy of a financial note signed by Pulitzer that was instrumental in piecing together his partial ownership of the Westliche Post . The St. Louis Police Department Library gave me access to the 1872 Minutes of the St. Louis Police Commission contained in books that had been found abandoned in a closet.

In Washington, D.C., I pursued at length a large cache of documents relating to President Theodore Roosevelts attempt to imprison Pulitzer for criminal libel. After years of claims by archivists that there were no such files, a threat of a lawsuit under the Freedom of Information Act from a prominent Washington law firm sped their discovery. The files provide for the first time an inside look at this important episode in abuse of presidential power.

Last, a small file folder at the Lake County Historical Society in Ohio contained a set of intriguing love letters to Kate Pulitzer while she was married to Joseph. They were signed only with an initial. But another set of documents, donated to Syracuse University in 2001, helped me identify her lover.

These were just several of the sources that had not been available to previous researchers and have greatly enhanced the story of Pulitzers life. At the same time, these findings and others also contradict a number of frequently repeated tales about him. These range from the claim that his mother was Catholic to the myth that he purchased the New York World while on his way to a vacation in Europe with his family. Rather than bog down the narrative of this book, I have placed any disagreements with previous accounts in my endnotes.

JAMES MCGRATH MORRIS

TESUQUE, NEW MEXICO

O n the afternoon of February 17, 1909, a small boat pushed off from a dock in Havanas harbor, cut through the pearl-green waters hugging the shoreline, and slid into the ultramarine-blue bay. Out ahead of it, one of the most luxurious private yachts in the world lay at anchor.

The length of a football field, the Liberty was rivaled in size and extravagance only by J. P. Morgans Corsair , which had set the standard of seagoing opulence for a decade. With two raked masts front and aft of a large smokestack, the white-hulled Liberty was like the beautiful schooners that had plied the oceans years earlier. I have never seen a vessel of more beautiful lines, said one man on board, who had served on a yacht belonging to the second white raja of Sarawak. Inside, the spacious vessel contained a gymnasium, a library, drawing and smoking rooms, an oak-paneled dining room that could easily seat a dozen people, quarters for its forty-five-man crew, and twelve staterooms fitted by a decorator who had designed furnishings for Londons Victoria and Albert Museum.

At this hour, on board all was still. The engines were silent, the bulkhead doors remained closed, and the upper deck gangways were roped off. The Liberty s owner, Joseph Pulitzer, had just gone down for his after-lunch nap, and severe consequences would befall anyone who disturbed the repose of Americas most powerful newspaper publisher.

Since becoming blind at the apex of his rise to the top, the sixty-one-year-old Pulitzer suffered from insomnia as well as numerous other real and imagined ailments, and was tormented by even the smallest sound. Every consideration possible was made to eliminate noise on board. Engraved brass plaques in the forward part of the ship warned, This door shall not be opened until Mr. Pulitzer is awake. At sea, the ships twin steam engines drove propellers set at different pitches and running at varying speeds in order to minimize vibrations carried through the hull. The Liberty was a temple of silence.

It was also Pulitzers cocoon. The demons that beset him never rested. For two decades, he had roamed the globe. At any moment, he might be found consulting doctors in Germany, taking baths in southern France, resting on the Riviera, walking in a private garden in London, riding on Jekyll Island, hiding in his tower of silence in Maine, or at sea. Since his yacht was launched the year before, water had become his constant habitat. In fact, the Liberty carried sufficient coal to cross and re-cross the Atlantic without refueling.

Wherever he went, it was in the company of an all-male retinue of secretaries, readers, pianists, and valets. In every practical sense, they had replaced his wife and children. From morning to night, these men tended to his every whim and kept the world at bay. By long practice, they had mastered handling his correspondence, discerned the most soothing manner by which to read books aloud from his well-stocked traveling library, and found ways to entertain at meals.