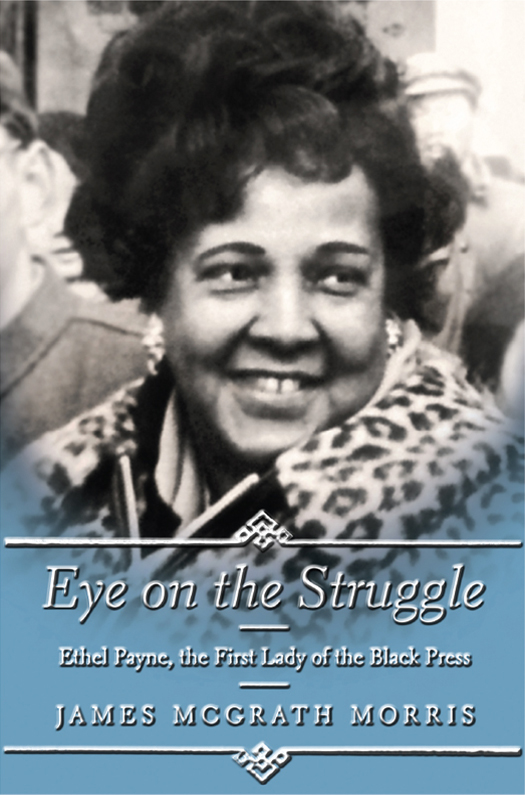

James McGrath Morris - Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press

Here you can read online James McGrath Morris - Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Amistad, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press

- Author:

- Publisher:Amistad

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

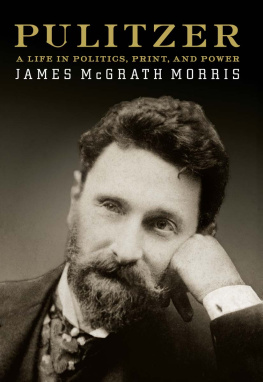

James McGrath Morris: author's other books

Who wrote Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In memory of

Gertrude Keaton

19092004

We are soul folks and I am writing for soul brothers consumption.

ETHEL PAYNE, 1967

A S THE SEVEN OCLOCK HOUR NEARED ON THE EVENING of July 2, 1964, President Lyndon Baines Johnson took a seat before a table at one end of the East Room in the White House. Nine months earlier the ornate room had been a somber place when President John F. Kennedys body lay in repose on the catafalque that had been made for President Abraham Lincolns casket in 1865. In contrast, the mood on this night was exuberant.

Resting on the table, to the left of a green blotter, was the final draft of the Civil Rights Act that had been approved less than five hours earlier by overwhelming numbers in the House of Representatives. The venerable New York Times hailed the new law as the most sweeping civil rights legislation ever enacted in this country and reported that civil rights leaders regarded it as a Magna Carta in the struggle to secure equal treatment and opportunity for the Negro.

All that remained now was for the president to add his signature to the bill. For that, Johnson needed an audience. Arrayed before him in rows of gold-colored chairs on the Fontainebleau oak parquetry and awash in klieg light sat two hundred and fifty of the nations most powerful and recognizable politicians, officials, and activists whose work, in one way or another, had led to this moment. The remainder of America watched on living room televisions.

When the president looked up through his wire-rimmed glasses he saw a vista of familiar white faces punctuated only occasionally by a dark countenance and almost entirely devoid of women. But sitting six rows back was a figure both female and black. In assembling a guest list suitable to the magnitude of this event, the White House had not failed to include Ethel Lois Payne.

WHILE UNRECOGNIZED BY MANY of the whites in the East Room, fifty-two-year-old Payne was an iconic figure to readers of the nations black press. The granddaughter of slaves and the daughter of a Pullman porter, the South Side Chicago native at midlife had inspiringly traded in a monotonous career as a library clerk for one as a journalist at the Chicago Defender, the countrys premier black newspaper. In a matter of a few years she had risen to become the nations preeminent black female reporter of the civil rights era, and during the movements seminal events in the 1950s it had been her words that had fed a national black readership hungry for stories that could not be found in the white media.

Her unflinching yet personable reporting had enlightened and activated black readers across the country and made her a trusted ally of civil rights leaders. Among those in the White House audience that night, labor leader A. Philip Randolph remembered her as far back as 1941 when she worked with him on his March on Washington Movement. For Clarence Mitchell Jr., the potent lobbyist for the NAACP, she had been a dependable confederate in the White House press corps during the Eisenhower administration. And Martin Luther King Jr. had first been the subject of her perceptive reporting during the initial days of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott when Payne crafted the earliest account of the black clergys ascension to the leadership of the civil rights movement.

On this night Payne was in temporary exile from her craft, serving as a Democratic Party functionary. But when she had sat in the ranks of the press, crowded together on the other side of the East Room, she had given black America a voice and presence at the highest reaches of power that could not be ignored. From challenging the white occupants of the White House and courthouses to reporting firsthand on events from Alabama to Africa and Asia, Payne had traveled the length of the civil rights movement that led to the legislative victory celebrated this evening. In doing so, she had served as both an emissary from and a representative for a large group of Americans long neglected by the mainstream media. She was, as she would later be called, the First Lady of the Black Press.

DESPITE A STORIED HISTORY dating back to 1827, the black press that employed Payne had unremittingly chronicled racism, eloquently protested injustices, impassionedly educated its people, and remainedlike most African American institutionscompletely out of sight of white America. To most white Americans the black press was a voice unheard, its existence unknown or ignored, said Enoch P. Waters, an editor at the Chicago Defender. It was possible for a white person, even one who believed himself well informed, to live out his three score years and ten without seeing a black newspaper or being aware that more than 150 to 250 were being published throughout the nation.

Until the civil rights movement made its mark, African Americans were absent from the pages of the nations white newspapers unless they were accused of a crime. When Payne was growing up, her hometown Chicago Tribune chose words like negress or southern darky when it mentioned the citys black residents. The important events of their lives such as graduations, marriages, and deaths were not commemorated in the white press. The useful news African Americans wanted about church, schools, entertainment, sports, not to mention politics, was nowhere to be found. It was in this capacity that Paynes employer the Chicago Defender and other members of the black press had found their initial role.

But the Chicago Defender, the Baltimore Afro-American, the New York Amsterdam News, the Pittsburgh Courier, and other black newspapers grew to have circulations beyond their cities and an influence greater than their press runs would lead one to believe. The most predominant media influence on black people was the black newspaper, recalled veteran reporter Vernon Jarrett, whose Negro Newsfront was the first daily radio news broadcast in the United States created by an African American. They wereour internet. They were our cement that helped keep us together.

DRESSED IN A DARK SUIT, President Johnson faced a bank of four large cameras arrayed in front of the table. Between them stood a blue and black metal box that held within it a glass screen on which the text of his speech was projected. He was the first president to make use of this new technology being called a TelePrompTer.

In a thick voice laced with a Central Texas drawl, the president began by invoking the gathering that 188 years ago had produced the Declaration of Independence, which embodied the American ideals of equality and inalienable rights. But, he said, these rights and these blessings of liberty had been denied to Americans not because of their own failures, but because of the color of their skins.

Such unequal treatment was impermissible under the Constitution, he said, and the law I will sign tonight forbids it. It will provide no special treatment for any group. Rather, Johnson continued, it does say that those who are equal before God shall now be equal in the polling booths, in the classrooms, in the factories, and in hotels, restaurants, movie theaters, and other places that provide services to the public.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press»

Look at similar books to Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Eye on the Struggle: Ethel Payne, the First Lady of the Black Press and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.