First published in Great Britain in 2016 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright David Bilton, 2016

ISBN 978-1-47386-701-7

The right of David Bilton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset by Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire HD4 5JL.

Printed and bound in England by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

A s with previous books, a great big thank you to the staff of the Prince Consorts Library for their help, kindness and knowledge during the pre-writing stages of this book. While some of the pictures come from books mentioned in the bibliography, the remainder are from a private collection.

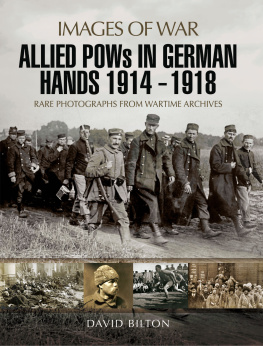

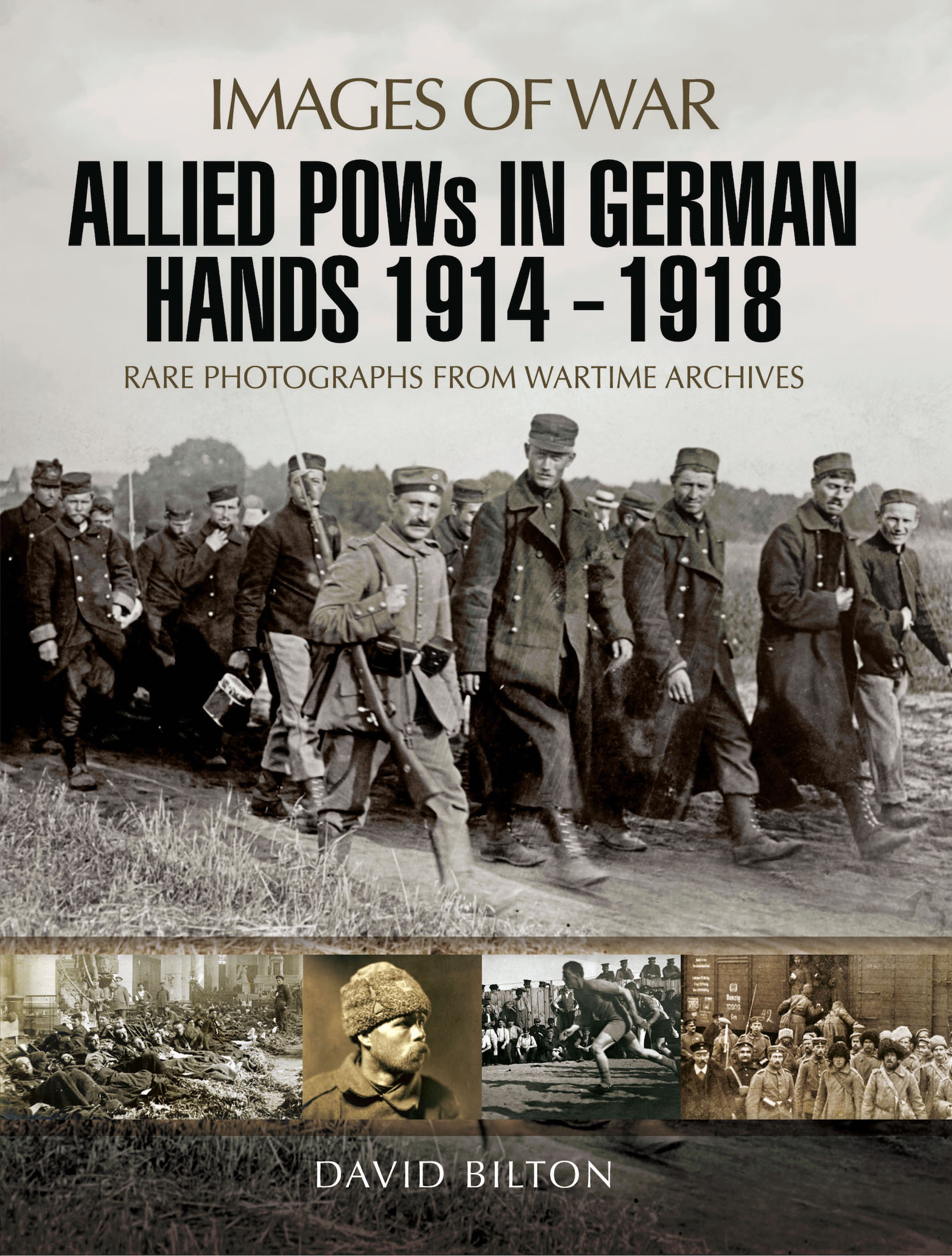

The utter exhaustion of fighting and capture is clearly shown in this photograph taken during the Somme Offensive in 1916. The great battle in the west. English prisoners resting on the road to Peronne.

Preface

D uring the war the German authorities published a photographic account of PoW life in a German prison camp. Although issued ostensibly by the Librairie de lUniversit Otto Gschwand in Fribourg, Switzerland it was printed in Germany in three languages, German, French and English. After the war, as part of the Armistice and Peace treaties, Germany published a book showing that it had not mistreated the prisoners and that any harm that befell them was their own responsibility.

A number of the illustrations from these books have been used in this book. What is interesting about those who bought photos as souvenirs is that most of them appear to have been French. As most Russians were poor that is probably the reason why there are so few private Russian cards, but there are also comparatively few British cards. Interestingly, in the German official pictures there are very few British present: most are photos of happy French and Russian prisoners.

Looking at the private purchase photographs kept by the inmates of the various prisons and reading the post-war testimony of the men held captive, few bear witness to the contents of either of these books. Neither show the appalling conditions recorded by some of the men. There are few if any photographs of the men working in the salt mines and other dangerous places. In general the men look fit, often quite happy and remarkably healthy. This contradicts the personal accounts. Which is true? Or are both true? Was it not as awful an experience for some as it was for others? Were some lucky and others not? While comparing the pictures with the text, readers will no doubt make up their own mind.

Introduction

T he concept of the prisoner of war is a relatively new idea. At the end of a battle, there had always been the dead and those that survived. What happened to the survivors depended on whether they had won or lost, who they were fighting and their position in society.

Throughout history wars have produced prisoners, men whose life was at the whim of the victor. What could be expected has changed through the centuries, but even with rules the position of the prisoner has never been secure. Even with the Geneva Conventions, a set of rules of conduct for warfare, security is not guaranteed, especially as not every country signed the conventions and many who did, only paid them lip service. Prior to 1931 there was no convention for prisoners, only regulations on the treatment of sick and wounded soldiers.

How have prisoners fared? Soldiers captured by the Ancient Greeks or Romans could end up as slaves but later become freemen, while those taken by the Aztecs were usually ritually sacrificed. In Japan, which had custom of ransom, prisoners were for the most part summarily executed. The rich could look forward to ransom but for most it was not an option. In early times the same fate awaited many who were non-combatants, merely citizens of the defeated nation. Religious wars were generally bloody affairs as it was felt better to kill the heretic. While the freeing of prisoners was a charitable act in Islam, Muslim scholars believed the leader of the Muslim force capturing non-Muslims could choose to kill, ransom or enslave them, or cut off their hands and feet on alternate sides. Fortunately, as warfare changed, so did the treatment of captives and the general population.

During the Middle Ages enslavement of enemy soldiers declined but ransoming was widespread and continued into the seventeenth century. For practical and ethical reasons, fewer civilians were taken prisoner: they were extra mouths to feed; and it was considered neither just nor necessary. The development of the use of the mercenary soldier also tended to create a slightly more tolerant climate for a prisoner, for the victor in one battle knew that he might be the vanquished in the next.

Enlightened thought during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries proposed that in war no destruction of life or property beyond that necessary to decide the conflict was necessary. During the same period the widespread enslavement of prisoners came to an end with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 which released prisoners without ransom. The idea of parole developed during the period. This was only allowable for officers because their word could be trusted. In exchange for swearing not to escape they received better accommodation and greater freedom, and for those who swore not to take up arms again against the captor nation they could be repatriated or exchanged.

German propaganda boasting of the number of PoWs held in less than five months of war.

During the eighteenth century a new attitude of morality in the law of nations, or international law, had a profound effect upon the problem of prisoners of war. The writings of Montesquieu, Rousseau and de Vattel were to help improve the treatment of prisoners: a captors only right over a prisoner was to prevent him doing harm, and they could be quarantined to prevent them returning to the fight. These ideas were not always adhered to and during the American War of Independence captured Americans were classified as criminals; no longer protected as PoWs, they could be treated differently. Many thousands died from starvation and exposure in crowded prison ships off the coast. Twenty years later the first purpose-built PoW camp was established at Norman Cross to house French prisoners from the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars. The prison was intended as a model prison, providing the most humane treatment possible to thousands of men. Food rations were as good as the food eaten by the local population.