YOUR TOWNS & CITIES IN WORLD WAR TWO

HULL AT WAR

1939 - 45

YOUR TOWNS & CITIES IN WORLD WAR TWO

HULL AT WAR

1939 - 45

THE AIR RAIDS

DAVID BILTON AND MALCOLM K. MANN

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright David Bilton and Malcolm K. Mann, 2019

ISBN 978 1 47386 0 902

eISBN 978 1 473860 926

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47386 0 919

The right of David Bilton and Malcolm K. Mann to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA,

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.com

This book is dedicated to the people of Hull

who lived through the air raids.

Acknowledgements

A great big thank you to Anne Coulson for reading the first draft, mostly air raid reports, for helping turn it into a readable text, and for checking the final version. It is also important for us to thank the Wells family of Hull who provided valuable information and photographs; Carol Tanner at the Hull History Centre, Mason Street, Hull; the parents of Second Lieutenant Stanley Duncan for family information; Mr and Mrs Harry Stephenson of Hull for his research; Lindsay Hayre of Hull, for research and photography; Deborah Berue of Hull for her assistance in proof-reading the book; and Mary Mann for her dedication and assistance during the research.

De La Pole Avenue the day after an air raid.

The remains of Mulgrave Street shelter.

Introduction

The City of Kingston-upon-Hull has the distinction of suffering longer and more frequently from German air raids than any other city or town outside London in proportion to its size. Why? One of the countrys most important ports, it boasted wharves, stores and industrial sites which, if destroyed, could have an effect on Britains ability to wage war. Destruction of its densely packed housing would displace and disable the workforce of the port and ancillary industries. Mass bombing, it was hoped, would weaken civilian resolve and help shorten the war. Hull was also, unfortunately, a relatively easy target in terms of distance, navigation and recognition: caught between the Humber and the North Sea it was comparatively easy to find. Then of course there were the reconnaissance flights carried out by the Luftwaffe during the early months of 1939. At the beginning of the war, ten strategic primary targets had been identified in Hull: the waterworks and gasworks at Stoneferry, Sculcoates power station, Saltend oil refinery and the six docks important targets that kept Hull at the forefront of the Blitz. Indeed such was the importance of Saltend that it was the target for the first daylight raid of the air war on Britain.

It is a plausible supposition that the Germans had considerable knowledge about the region, possibly provided unknowingly by Charles Ayre. He was the owner of a motor launch which he used to transport trawlermen who had missed their sailing to their boat and to take postcard photographers around the coast. During the 1930s he took German marine engineers across both sides of the Humber as they touted for work. No one at the time thought anything untoward about the sketches they made or the photographs they took. Naturally there were spies. Propaganda said they were everywhere and notices in the docks raised the awareness of speaking to strangers.

This is a brief account of the many raids faced by the men, women and children of Hull. Although not covered in this book, the attacks did not affect only the city. In other parts of the East Riding 121 were killed: 82 civilians and 39 service personnel. In Bridlington, Hornsea and Withernsea, 44 were killed. Attacks on the Blackburn aircraft factory at Brough, random bombing, and attacks on the Hull docks decoy resulted in the deaths of 22 people in Bilton, Hedon and Preston. The Luftwaffe also bombed the RAF bases at Catfoss, Driffield and Leconfield. Further damage along the coast was caused by German mines coming loose and drifting ashore. A single V1 fell in Willerby in 1944 causing damage to Springhead pumping station and nearby housing.

Hulls position also meant that it was on the way back for bombers that were detailed to attack targets inland. While the RAF jettisoned unused bomb loads in the North Sea, the same did not apply to the Luftwaffe. Pilots who failed to find their target could and did drop their loads anywhere over Britain, including Hull.

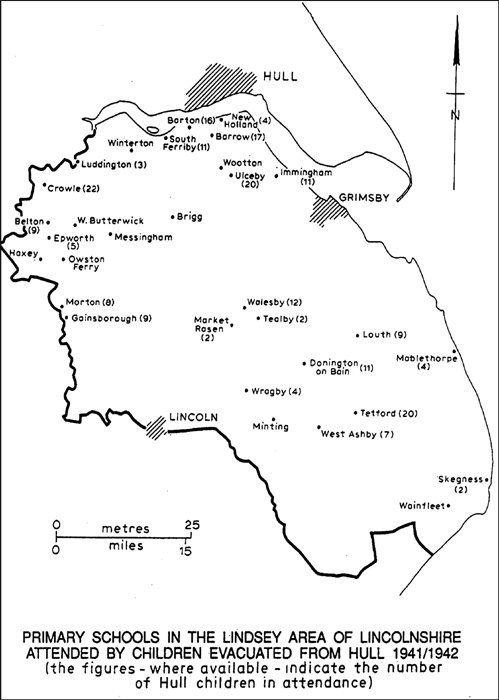

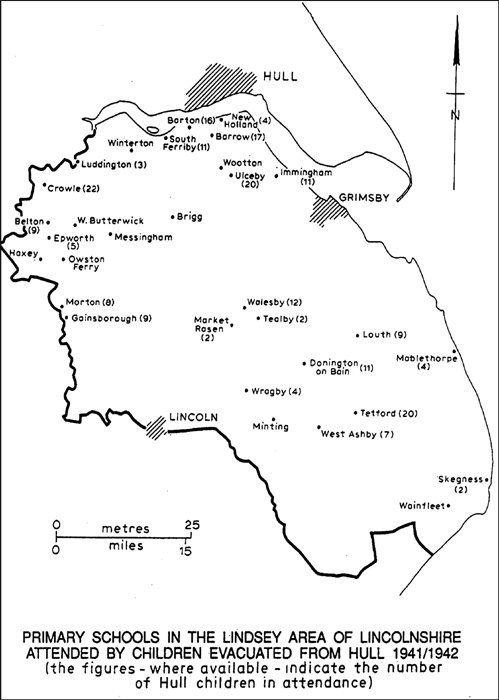

The raids began on 19 June 1940 and continued until March 1945 (the last piloted raid on Britain). Though no bombs were dropped on Hull during 1944, this meant nearly five years living in fear of a raid. As a result of the intensity of the bombing, around 38,000 children were evacuated and entire secondary schools were relocated. Some went across the Humber to Lincolnshire, some were sent many miles to find a new temporary home. Many children, like the co-writers mother and uncle, stayed, but from 1942 onwards many started to return.

The damage reports and number of casualties clearly indicate the severity of the bombing. The official number of civilian deaths caused by enemy action is 1,200: not all have graves; some are buried in a mass grave because they could not be identified; and some simply disappeared or, when found, existed only as body parts. Typical examples reported in the official accounts show how little identifiers had to go on: remains and a hand found at the side of a house in Rowlston Grove weeks after the road had been bombed; or on 10 March 1941, in Cleveland Street, a female scalp, forehead and right eyebrow; or, after the 22 February 1941 raid, in the street lay the remains of a pair of legs, shoulder and arm.

Some children were evacuated from the city but not to the same extent as in London. Many went a few miles across the Humber to Lincolnshire, which apart from Grimsby was highly unlikely to be bombed.