Contents

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright David Bilton 2012

ISBN 978 1 84884 878 8

eISBN: 978 1 78303 882 4

The right of David Bilton to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Gill Sans

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Acknowledgements

The book turned into three. Sorry to everyone at home, and thanks.

As with previous books, a great big thank you to Anne Coulson for her help in checking the text and to The Prince Consorts Library for all their help.

Errors of omission or commission are mine alone.

Not all barracks were permanent. Here a large marquee to is being erected to house returning troops.

Introduction

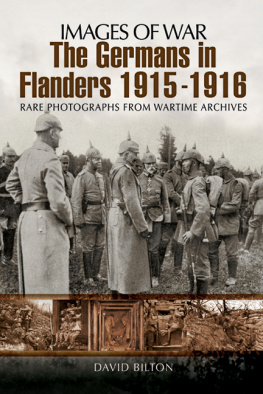

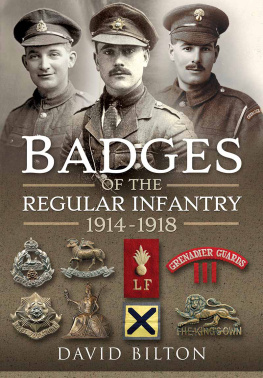

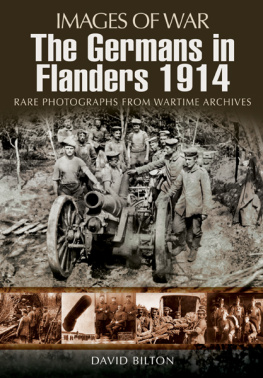

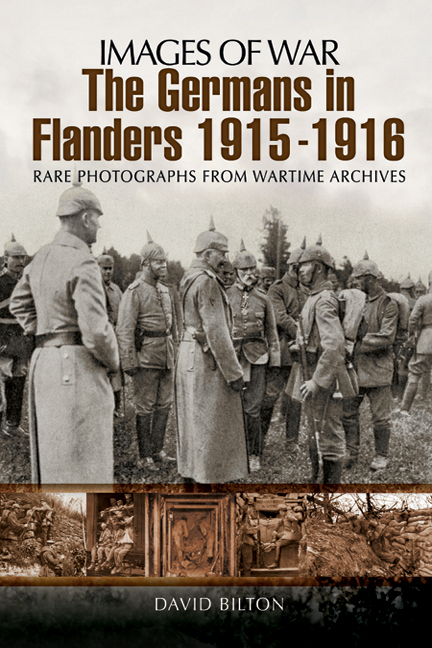

T he purpose of this series of books, The Germans in Flanders 1914 , The Germans in Flanders1915-1916 and The Germans in Flanders 1917-1918 , is not to analyse, in any depth, the strategic, tactical, political or economic reasons for the fighting in Flanders but rather to chronicle the events that happened there during 1914 1918 and how events elsewhere impacted upon these. The brief words rely on the pictures to tell much of the story: pictures from a private collection and from texts published during the period of this history (detailed in the bibliography). The books are not necessarily a chronological photographic record as some periods were more fully recorded than others and in many cases what was photographed in 1915 was just as valid a record as if it had been taken in 1918; in fact, these books are more an attempt to provide a cameo of the experiences of the German Army in Flanders during the Great War. For most of the time, armies do not fight, and the photographs portray life outside the trenches as well as in them.

As with my earlier books on the German Army, I have included a day-to-day chronology to show what was happening across the Belgian Flanders Front from the German point of view. However, as Flanders is a coastal area and the occupied territory closest to the British mainland, the book also deals with events at sea and information about aerial activity.

Most of the book is centred on Ypres and its immediate environs because that is where the actual fighting occurred. However, most of Belgium was occupied; the effect of the war was sometimes felt directly, more often indirectly, throughout the country.

Flanders also provided the German air force with numerous bases, some of which were used to attack England. Quite regularly since 1914, single-engined aeroplanes had braved the Channel, one or two at a time, to drop a few small bombs along the coast. Their favourite target was Dover Harbour. They had become a routine nuisance.

The remains of Zonnebeke church.

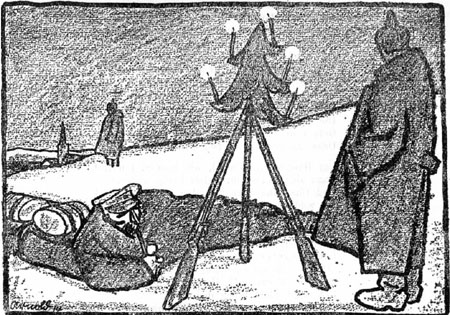

Zeppelins were usually employed for bombing, but in late 1916 an aircraft from Flanders bombed London. Lieutenant Ilges (photographer and bomb aimer) and Deck Officer Brandt (pilot), both naval airmen, took off from Mariakerke near the Belgian coast in a single-engine LVG biplane; primarily a reconnaissance aircraft, it had the range to take it to London and could be equipped with bombs. Ilges had photographed the coast on many occasions but had not gone far inland. The flight, unlike the previous coastal trips, was a meandering journey through Essex and up the Thames. During the trip Ilges photographed aerodromes, factories, docks and other choice targets and then, above London, he took more pictures before releasing his load of six twenty-pound bombs. Brandt flew south, managing to evade the British squadrons at Dover and Dunkirk, but engine trouble ended the flight over French lines and the two were taken prisoner. Little notice was taken of the flight or the capture of its crew. The British were too busy exulting over the two Zeppelins that had been shot down. However, The Times warned in an editorial that it was likely that there would be further such visits on an extended scale. The following summer German bombers came to London in formation.

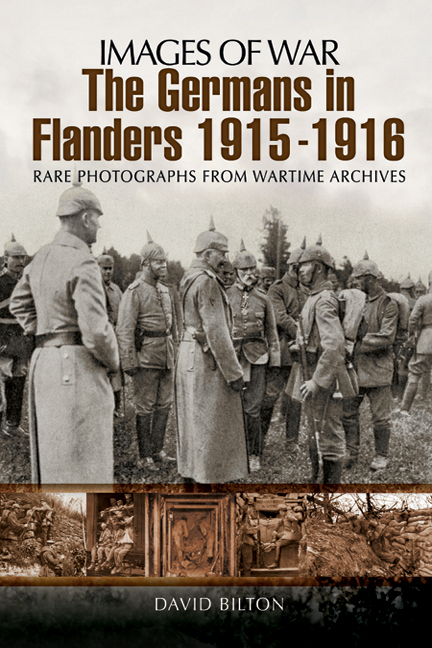

Crown Prince Wilhelm, the Kaisers son, with his entourage, watching training manoeuvres in Flanders.

Flanders was an important area for naval offensive operations and had to be guarded against Entente naval attack and the possibility of naval-supported invasion. To this effect the sea-front was guarded by regiments of marine artillery. Thirty guns of the heaviest calibre had been set up there, among them five of 38 cm., four of 30.5 cm., and besides them a large number of quick-firing guns from 10.5 to 21 cm. calibre. Manning these fortifications and the coastal trenches employed large numbers of men.

The Naval Corps, the troops defending the naval areas, was instituted under the leadership of Admiral von Schrder on September 3, 1914, and played a part in the taking of Antwerp on October 10, 1914. Naval Corps General Command had its headquarters at Bruges. Its infantry consisted of three regiments of able seamen and the marines. The latter in particular played a part in the great battles in Flanders in 1916 and 1917.

Again, taking the offensive to the Royal Navy required boats, aircraft and of course submarines. In 1916, a quarter of all available U-boats were assigned to the Naval Corps in Flanders. Initially they were small, relatively slow boats but later models were over three times the weight and half as fast again. However, their limited range meant that they could operate from Flanders only against the south and east coasts of England. Most mine-laying submarines also operated from the Flanders coast. Zeebrugge was an important base for the maintenance of these submarine types. When the U-boat campaign opened on February 1, 1917, there were already 57 boats in the North Sea of which the Naval Corps in Flanders had at its disposal 31 U-boats of different types.

Next page