First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

South Yorkshire.

S70 2AS

Copyright David Bilton, 2007

ISBN 978-1-84415-502-6

The right of David Bilton to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying,

recording or by any information storage and retrieval system,

without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI UK

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, Wharncliffe Local History

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact:

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England.

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

O nce again a big and meaningful thank you to my family who were all pleased that it was supposed to be more of a picture book than my previous efforts. What would I do without Anne Coulson to read my proofs or the Prince Consorts Library to assist me in my research? Thank you. As always it was a pleasure to work with the wonderful team at Pen & Sword.

Any errors of omission or commission are mine alone.

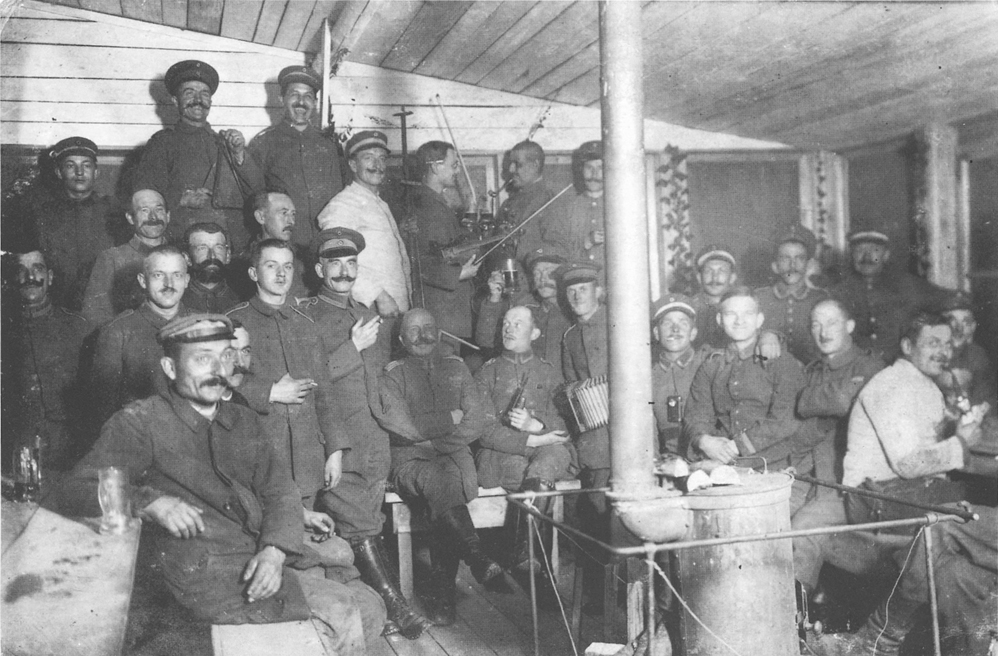

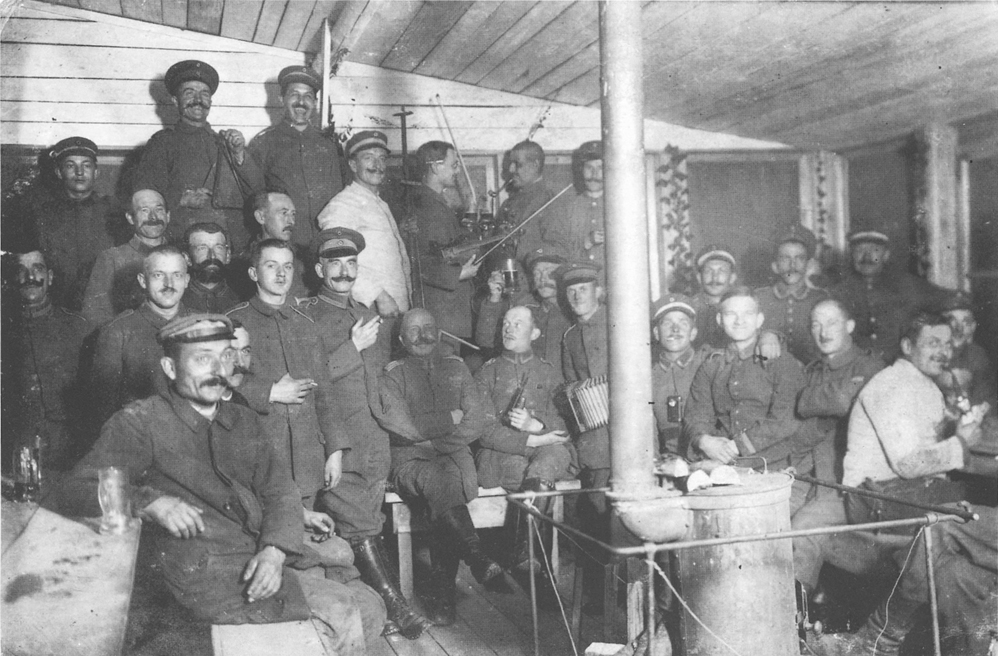

Even with shortages, life could be convivial behind the lines.

A t the start of 1917, Germany was fighting on both the Western and Eastern Fronts as well as contributing substantial numbers of troops to the fighting on the Southern Front, the Balkans and in the Middle East; tens of thousands of men were also involved in Home Defence and occupation duties in the captured territories.

On the Western Front alone, the German lines stretched for over four hundred miles, starting in the north on the Belgian coast, passing through the wet plains of Flanders down into the chalk flatlands of the Somme, continuing through the hills of Champagne and ending in the mountainous area leading to the Swiss border on the eastern flank. Facing them were the armies of Belgium, France and her colonies, Britain and the British Empire, with a division of Russian troops; these were to be joined during the year by troops from Portugal and the United States, although the German High Command deduced that the latter would not be effective until the spring of 1918.

As well as the military problems on the different war fronts that needed solutions there was a further non-military front to take into account the Home Front; here there were problems of a different kind. There were food and coal shortages that affected productivity and health (especially among the young, whose physical development was adversely affected, and the old, who suffered increased mortality rates). Manpower was short; the armed forces had first call on any production, and essentials like soap had become scarce; ersatz products, like coffee made from acorns and chicory, became the norm for those who could not afford the prices of the Black Market or were unable to get into the countryside at the weekend to buy food directly from the farmers weekend excursions that became known to the population as the Hamsterfahrt (Hamster journey). The cereal and potato harvests had dropped by over fifty percent by early 1916 and bread (K-brot war bread) was made from oat and rice meal, ground beans, peas and corn meal. Butter was available only to the rich; its replacement was made from curdled milk, sugar and food colouring. Similarly, cooking oil was replaced by extracts from red beet, carrots, turnips and spices, fats by a mixture of crushed cockchafers (beetles) and linden wood. Neither was sausage, a staple food, safe from economy measures: it was now produced from animal scraps, plant fibres and water.

Clothing was likewise in short supply and, when available, was supplemented by material such as paper technically this was known as stretching supplies, and indeed when it got wet it actually stretched! Mounting casualties, with no sign of victory, had a negative effect upon peoples attitudes, commitment to the war and productivity. The use of schools for military purposes, coupled with a shortage of school teachers, meant that many children received little education; an upside to this was that they were available to help in factories and on farms, but many of them turned to crime and the crime rate increased this was blamed on the lack of male role models available to keep them in check. On top of this, the winter of 1916/1917 was the coldest for years with the temperature dropping to 30C, forcing the closure of restaurants, stores and theatres, due to an acute shortage of coal that industry had first call on. The Turnip Winter, where children stole each others rations and women worried more about their childrens hunger than about their husbands at the front, was not an auspicious start to 1917.

Increasing instability, demands for manpower in industry on the Home Front, and extended commitment at the front meant that the German army in manpower terms was overstretched even to hold the line defensively let alone mount an offensive in the west on what was considered the decisive front. A further drain on German manpower had been the German and Allied offensives in France; during the fighting of 1916 on the Somme and at Verdun, Germany had incurred enormous casualties. Estimated losses on the Western Front alone amounted to over 960,000, with materiel losses of nearly 2000 field guns, over 250 mortars and 1000 machine guns. German peace proposals at the end of 1916 were rejected so the war would continue.

In 1917 the uneasy state of Germany offered some encouragement to the Allied camp; a reduced bread ration in April had caused disturbances and riots and, in July, there were mutinies on several battleships. Hindenburg and Ludendorff threatened to resign unless the Chancellor retired, which he duly did on 13 July, and, most disappointingly to the Army High Command, the Reichstag passed a resolution demanding a peace of understanding.

As a result of the previous years fighting, the German army of 1917 was severely stretched, and during 1917 the general reserve stood between four and six divisions; positional change was needed and would soon come. By 1918 further events had transformed the Western Front and the stalemate no longer existed mobile warfare had returned and eventually the war would be decided one way or another.

It is not the purpose of this book to analyse in detail the strategic, tactical, political or economic reasons for this situation or its results, but merely to chronicle the events of 1917 and 1918 in words (briefly) and pictures almost all from the German side of the wire and mostly concentrated on their British opponents. I have not tried to chronicle every battle in detail but have used the Battle for Arras to show the typical experiences of a front line unit and soldier. Neither is it a chronological photographic record; it is an attempt to provide a snapshot of the experiences of the German Army on the Western Front over a two-year period. Similarly the day-to-day chronology is taken from the German point of view. Not every day is listed; for any day apparently missing read Im Westen nichts Neues In the West nothing new, or as it is usually translated,

Next page