The Bitter Harvest of War

New Brunswick and the Conscription Crisis of 1917

The New Brunswick Military Heritage Series, Volume 11

The Bitter Harvest of War

NEW BRUNSWICK AND THE CONSCRIPTION CRISIS OF 1917

Andrew Theobald

Copyright 2008 by Andrew Theobald.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Barry Norris.

Front cover illustration courtesy of New Brunswick Museum, 1988.67.17.

Back cover illustration: Bushman and Sawmill Hands Wanted, Canadian War Museum, 19900055-003.

Cover and interior page design by Julie Scriver.

Printed in Canada on 100% PCW paper.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Theobald, Andrew, 1978

The bitter harvest of war: New Brunswick and the Conscription

Crisis of 1917 / Andrew Theobald.

(New Brunswick military heritage series; 11)

Co-published by: New Brunswick Military Heritage Project.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-86492-511-4

1. Conscription Crisis, 1917.

2. World War, 1914-1918 New Brunswick.

3. New Brunswick History 1867-1918.

4. New Brunswick Ethnic relations History.

I. New Brunswick Military Heritage Project II. Title. III. Series.

FC2473.9.C6T44 2008 971.5103 C2008-900511-2

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), and the New Brunswick Department of Wellness, Culture and Sport for its publishing activities.

Goose Lane Editions

Suite 330, 500 Beaverbrook Court

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

New Brunswick Military Heritage Project

The Brigadier Milton F. Gregg, VC

Centre for the Study of War and Society

University of New Brunswick

PO Box 4400

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5A3

www.unb.ca/nbmhp

Contents

Chapter one

The Lessons of World War, 1914-1916

Chapter Two

Vimy Ridge and Conscription,

January November 1917

Chapter Three

The Crisis Manifest,

December 1917 November 1918

Elements of this work were previously published in:

Une loi extraordinaire: New Brunswick Acadians and the Conscription Crisis of the First World War, Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region 34 (Autumn 2004): 80-95.

Divided Once More: Social Memory and the Canadian Conscription Crisis of the First World War, Past Imperfect 12 (2006): 1-19.

The author is grateful to both Acadiensis: Journal of the History of the Atlantic Region and Past Imperfect for their permission to reprint relevant sections in this work.

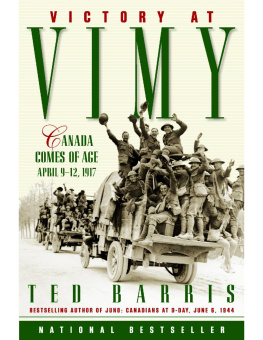

Canadian troops crossing the shell-torn battlefield of Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917. LAC PA-1020

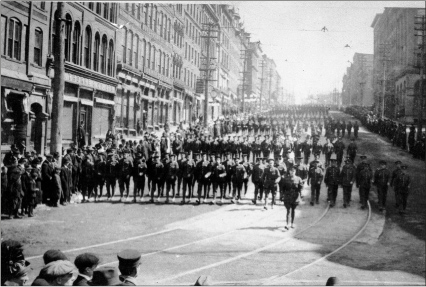

Saint John was the focal point of military activity in New Brunswick during the Great War, and it started early: the 26th (New Brunswick) Battalion marches down King Street in column of companies just prior to going overseas in June 1915. PANB P98/16

Introduction

In the early morning gloom of Easter Monday, April 9, 1917, men of the 26th (New Brunswick) Battalion of the Canadian Corps surged out of their trenches and stumbled forward over shell-torn ground. The deafening roar of artillery and clatter of machine-gun fire surrounded them, but they were not alone. To their left and right along eight kilometres of front, 100,000 other Canadian soldiers thousands more New Brunswickers among them moved in unison. Among them were men who had fought their way through the gas of Ypres and the dreary battles of Festubert and Givenchy in 1915, the defensive victory at Mont Sorrel and the slaughter of the Somme in 1916. Weighed down by their heavy packs and weapons, and surprised by the snow in the crisp dawn air, the Canadians had every confidence that this battle would go much better. Above them lay Vimy Ridge and its imposing network of German tunnels and interlocking defensive positions, which had defied the best efforts of the French and British armies for two years. If the New Brunswickers advancing on that fateful day had been at home they might have been enjoying a mornings walk in the woods where the snow would hardly have been a surprise fishing for smelts or preparing for church. Instead, they were spearheading the most important Canadian victory of the First World War.

Many years later, Gregory Clark, who had served as a lieutenant with the 4th Canadian Mounted Rifles at Vimy, recalled with pride the victory on that cold April Monday: As far as I could see, south, north along the miles of the ridge, there were the Canadians. And I experienced my first full sense of nationhood. New Brunswickers shared in this pride. The 26th Battalion, part of the 5th Infantry Brigade of the 2nd Canadian Division, were in the first wave. On their part of the front and that of the 1st Canadian Division to the south, the ridge was little more than a gentle rise across a long flat crest, which then dropped away suddenly. In the 26th Battalions sector, it was only two kilometres to the edge of the escarpment, with the village of Vimy just below. The New Brunswickers task, along with four other battalions on the 2nd Division front, was to overrun the German front line and push forward to a depth of fifteen hundred metres. In the horrific trench combat of the First World War, these distances seemed much greater. The 26th Battalion, and the rest of the 5th Brigade, accomplished their task in under two hours, consolidating on the Black Line where the second wave passed through, over the escarpment and deep into the German positions. All along the line that day the attack succeeded beyond expectation, as the Canadian Corps drove the Germans off the most impregnable position on the Western Front. It proved to be Canadas defining moment and the place, historians say, Canada came of age as a nation.

But the cost was horrendous. In just three days of bitter fighting, 11,000 Canadians became casualties, with nearly 4,000 dead: another butchers bill to add to the nearly 30,000 Canadians already killed in the war. New Brunswicks only infantry battalion lost two hundred men at Vimy, and for weeks afterwards local newspapers were full of the lists of the dead, the wounded and those who had simply disappeared. The New Brunswickers were as proud of their central role in the victory as any of their comrades, but where would the reinforcements needed to replace the thousands of casualties come from?

The Battle of Vimy Ridge perfectly encapsulates the paradox of the First World War: both a great Canadian triumph and a costly victory in a brutal war that fractured the basic fabric of the country. For Vimy was fought by an all-volunteer force, but losses on that scale could no longer be sustained by voluntary enlistment. In searching desperately for those badly needed reinforcements, Canadians decided in 1917 to adopt compulsory military service. This action led to political skullduggery, racist propaganda, battles in the streets and desperate searches to round up equally desperate deserters. Such was the cost of victory in the First World War, a wound to both Canada and New Brunswick so jagged that its scar is still visible today.

Next page