To James Ripley Jackson Douglas.

Prologue

His captors didnt respond, although one of them made an involuntary move with his right hand toward the pistol holstered at his waist. The German smirked at the reaction. I have also heard Canadians are a collection of drunken cowboys who would shoot an unarmed man without a second thought.

The mans gaze never wavered as he stared at the Canadian o ffi cer in charge. Well, you had better save your ammunition because you will need it. The attack you are planning is the worst-kept secret of the war. It is also the biggest joke the Kaiser has heard in a long time.

The three Canadians in the dimly lit dugout kept silent, not even flinching when another artillery shell shook the foundations, cascading debris down from the rafters. The soldiers appeared content to let their prisoner keep talking. After all, he might blurt out some kernel of information that could save a few lives in the days ahead.

Your British and French friends tried the same thing and lost over a hundred thousand men, the German continued. What makes you think a ragtag collection of farmers and fishermen from your country can do any better?

The Canadian o ffi cer in charge made a dismissive sideways gesture with his head, and his two companions grabbed the enemy o ffi cer by the arms, preparing to lead him away. He shook o ff their grasp, pulled his greatcoat tightly around his shoulders, and sneered at his adversary.

Maybe, just maybe, your men will reach the top of Vimy Ridge, he hissed. But they will be able to ship the survivors home to Canada in a rowboat.

Introduction:

The War to End All Wars

It was also known as the Great War, but, as with most military slogans, the phrase proved to be both nave and totally off the mark. History has shown that World War I was not the war that ended all wars it actually sowed bitter seeds for future conflicts. In addition, with an estimated body count of more than 15 million combatants and civilians, as well as over 22 million wounded, there certainly was nothing great about the bloodbath that lasted from July 28, 1914, until November 11, 1918.

The fuse that set off millions of tonnes of explosives was the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, in the Bosnian capital of Sarajevo. When Austro-Hungary blamed Serbia for the assassination and threatened retaliation, Serbias ally, Russia, began to assemble its troops. Bound by a treaty with Austro-Hungary, Germany considered this mobilization an act of aggression, and declared war on Russia. This brought the allied powers of Great Britain and France into the conflict, lined up with Russia against the central powers led by Germany and Austro-Hungary.

The deadly domino effect caused by a lone assassin would hold the entire world in a death grip of insanity for the next four and a half years despite the widespread belief from day one that the war would last no more than a few months. Those countries that became engaged in the conflagration would lose an entire generation of their youth, with men and women from all walks of life perishing in the trenches of Flanders and other muddy battlefields across northern Europe.

It would take the combatant countries years to regain what they had lost, both physically and financially just in time for renewed acts of aggression that would lead to another, and even more devastating, world conflict.

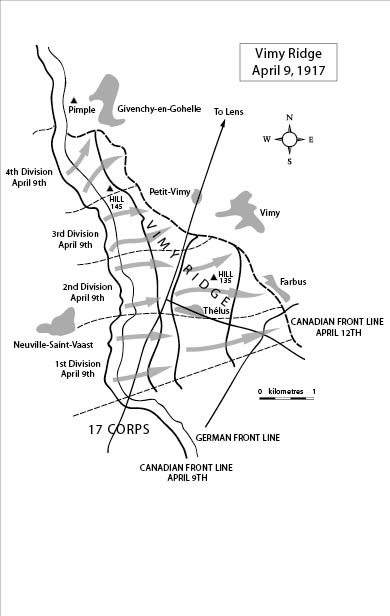

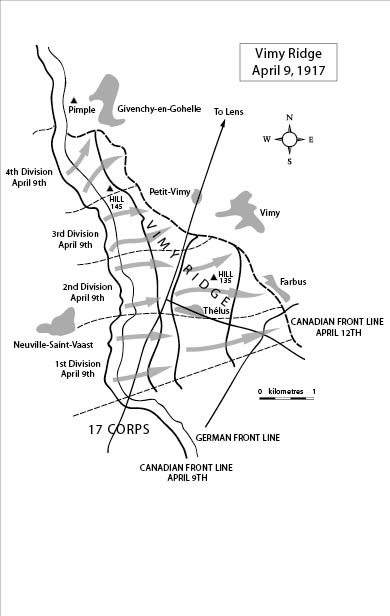

It is difficult to sift historically through the ruins of World War I and come up with anything positive. But one thing Canada gained from participating in this barbarous affair was a sense of pride at having stood shoulder to shoulder with some of the most powerful nations on earth to defeat a common enemy. And that sense of pride began to take shape on April 9, 1917, at the Battle of Vimy Ridge.

Chapter 1

Innocence Lost

Church bells rang. People danced in the streets. Brass bands played martial music as zealous youths shouldered wooden rifles and marched through town to the cheers and applause of adoring crowds. Recruiters turned a blind eye as young boys barely into their teens lied about their age so they could sign up to go overseas and fight against the Hun.

This was the nationalistic fever that gripped Canada in the summer of 1914 when war was declared against Germany. Since Confederation in 1867, Canadians had experienced little in the way of armed conflict other than sending a battalion of volunteers to assist Great Britain in the Boer War in 1899. That three-year conflict in South Africa involved some 7,000 Canadians, including 12 women nurses, and resulted in 267 Canadian fatalities. It had been considered a noble cause, and the romance of battle had grown in the minds of most Canadians every year since. By 1914, when war clouds were forming over Europe, the majority of able-bodied males from Victoria to Halifax were ready, in fact eager, to fight for king and country.

The Canadian government perhaps realizing that the country was ill prepared militarily, with a militia numbering just over 3,000 and a fledgling navy had been little more than lukewarm in its official reaction to the situation overseas. When Britain declared war against Germany on August 4, 1914, Canada issued this statement: If unhappily war should ensue, the Canadian people will be united to maintain the honour of the empire.

But a groundswell of patriotism flared up across the land like a grass fire on a tinder-dry prairie and, by August 10, authorization had been granted for the formation of the Princess Patricias Canadian Light Infantry Regiment. The regiment was named after the only daughter of the then-serving governor general of Canada, Prince Arthur, the Duke of Connaught, who was the third son of Queen Victoria. The ranks of the PPCLI were filled in just over a week, made up for the most part of trained ex-regular soldiers who had served in the British army during the Boer War. The PPCLI was financed privately, mainly by Captain Hamilton Gault of Montreal. On December 21, 1914, the regiment, under the command of the governor generals military secretary Colonel F.D. Farquhar DSO, set foot on French soil and was the first Canadian unit committed to battle.

Back home, volunteers continued to pour into the recruiting stations and, by late September, more than 30,000 hastily trained soldiers marched out of the Valcartier mobilization camp near Quebec City to board trains for the East Coast. On October 1, officers and men stomped proudly up the gangplank of 33 ocean liners including the RMS Olympic , sister ship to the RMS Titanic and set sail for England under the protection of British Royal Navy escort ships. It was the largest convoy ever to cross the Atlantic. The enthusiastic Canadians crowded the railings of these transport ships as the flotilla came within sight of the English coast.