ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The writing of this guide has been greatly assisted by the help of a number of people. The authors are indebted to the historians of the Canadian, British and German armies, who wrote about the history of the area and the battles which occurred there almost a century ago. Without their careful recording of events, modern interpretation of the battles would be impossible. They also wish to express their grateful thanks, in particular, to Lieutenant Colonel Phillip Robinson RE, who placed at their disposal his superb collection of maps, diagrams and photographs and went to considerable trouble to prepare it for publication. Other members of the Durand Group were also extremely helpful, providing technical advice and assistance with a wealth of material relating to the underground workings beneath Vimy Ridge. Our thanks go, too, to Lieutnant Colonel Mike Jackson of the Canadian Army, for information relating to his uncle, Corporal AH Clubbe. We are also grateful to Laurie Sheldon who drew the maps for the car tour and Arlene King for her kind assistance and hospitality. As always, we wish to express our appreciation of the friendly and supportive team at Pen and Sword Books.

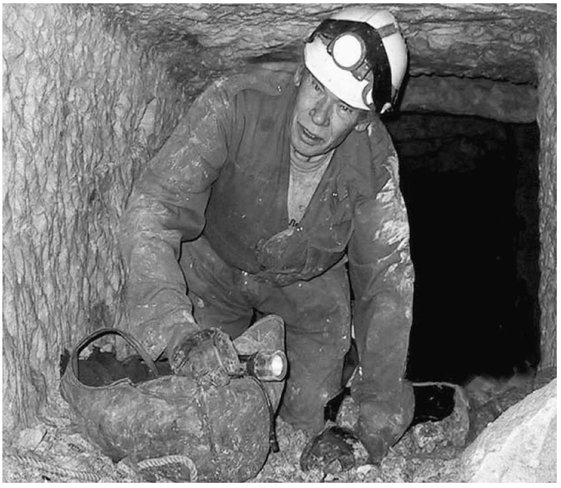

Lieutenant Colonel Phillip Robinson in action with the Durand Group below Vimy Ridge

CASUALTY ANALYSIS: RESERVE INFANTRY REGIMENT 261

Just as this guide was going to press the detailed Roll of Honour for Reserve Infantry Regiment 261 became available for study. Because that regiment played a prominent role in the defence of Vimy Ridge this section, which is devoted to the outcome of that work, has been added in. According to the regimental history of Reserve Infantry Regiment 261, the last of the regiments to be withdrawn from Battle for Vimy Ridge, the defence had cost it fatal casualties of nine officers, nineteen NCOs and eighty six junior ranks. Five officers, thirty six NCOs and 199 junior ranks were wounded, whilst the list of missing amounted to six officers, sixty nine NCOs and 451 junior ranks. The overall totals: twenty officers, 124 NCOs and 736 junior ranks were high, reflecting the intensity of the fighting and the stubborn defence the regiment mounted. Closer examination of the regimental Roll of Honour yields a number of interesting facts.

In addition to the 114 definitely killed on Vimy Ridge on or after 9 April 1917, a further 94 were listed as missing (presumed killed) during the same period. This suggests, in turn, that a total of about 430 of the missing were in fact captured. The 208 fatal losses did not fall on the companies equally. The hardest hit were 1st (31), 9th (29), 10th (33) and 11th (24). At the other end of the scale were 6th (3), 7th (2) and 8th (1). In part this was a reflection of their different roles. The front line was manned from south to north by the 9th, 11th, 1st and 3rd Companies. The 9th and 11th fought on, until surrounded at around 3.30 pm on 9 April 1917. Very few men from these companies fought their way back through to the positions in rear; the majority of the survivors, wounded or not, must have been captured, thus boosting the numbers of missing after the battle. The 10th Company mounted a series of local counter-attacks throughout the morning and early afternoon: hence their heavy losses. Any of its wounded must also have been captured.

The companies of the 1st Battalion fought on for the longest period, with the 1st and 3rd holding the front and 2nd and 4th Companies involved in a series of counter-attacks. When this battalion was ultimately withdrawn, it was greatly reduced in strength, but there were relatively few prisoners from this source. A total of eight officers, thirty eight NCOs and 280 junior ranks had already been killed or evacuated wounded. The 2nd Battalion was in Brigade reserve and, with few exceptions, spent most of the battle manning the Second Position, suffering far fewer casualties in the process, although 5th Company, which was involved in defending the Intermediate Position, suffered seventeen fatal casualties.

Of the 208 killed, or missing believed killed, during the battle and a further sixty nine who fell during the previous six weeks, only forty eight have known graves. Forty five are listed below and three others in the car tour section. Of these, only eight were killed on or after 9 April 1917. In other words a mere three point eight per cent of the total fatal casualties during the main battle were buried and recorded in the correct manner and the body of one of these (Fusilier Wilhelm Pohl) was not discovered until after the war when, for some reason, he was taken all the way to Sissonne (near Laon) for burial. Of the sixty nine other members of the regiment who were killed between the end of February 1917 and 8 April, forty (fifty eight per cent) repose in known graves. If those who were killed during the final bombardment are excluded the proportion properly accounted for rises sharply. It is a stark illustration of the care the German defenders took to recover their dead whenever possible, compared with the unmarked burial in shell holes or abandoned trenches of the German fallen by the Allies after the battle. One strange fact is that, according to the German Volksbund, Fsilier Wladislaus Dronczkowski appears to have two graves in the cemetery at Neuville St Vaast/Maison Blanche.

Just as there is a cluster of men from Reserve Infantry Regiment 262 in Block 2 at Neuville St Vaast, the same applies in Block 9 for the men of Reserve Infantry Regiment 261. Try to make time to visit their last resting place as you tour the area.