As far as I could see, south, north

along the miles of the Ridge, there were

the Canadians. And I experienced my

first full sense of nationhood.

Lieutenant Gregory Clark, M.C.

Weekend Magazine, Novembers 13, 1967

First published in Great Britain in 1986

and re-printed in this format in 2012 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Pierre Berton 2012

ISBN 978-1-84884-862-7

978-1-78303-723-0

The right of Pierre Berton to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11pt Ehrhardt by

Mac Style, Beverley, E. Yorkshire

Printed and bound in the UK by

CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CRO 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation,

Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military,

Pen & Sword Discovery, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime,

Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics,

Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and

Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

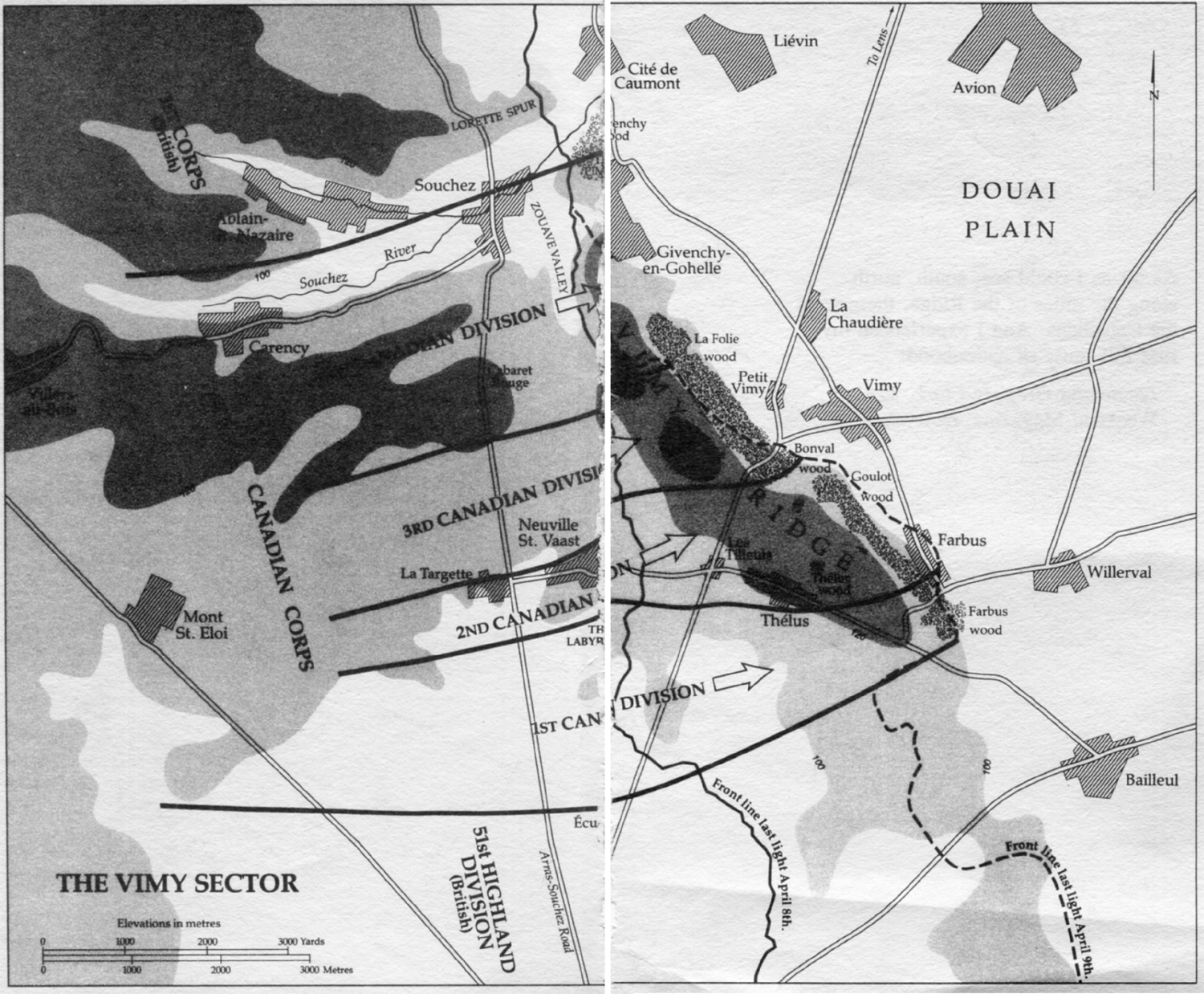

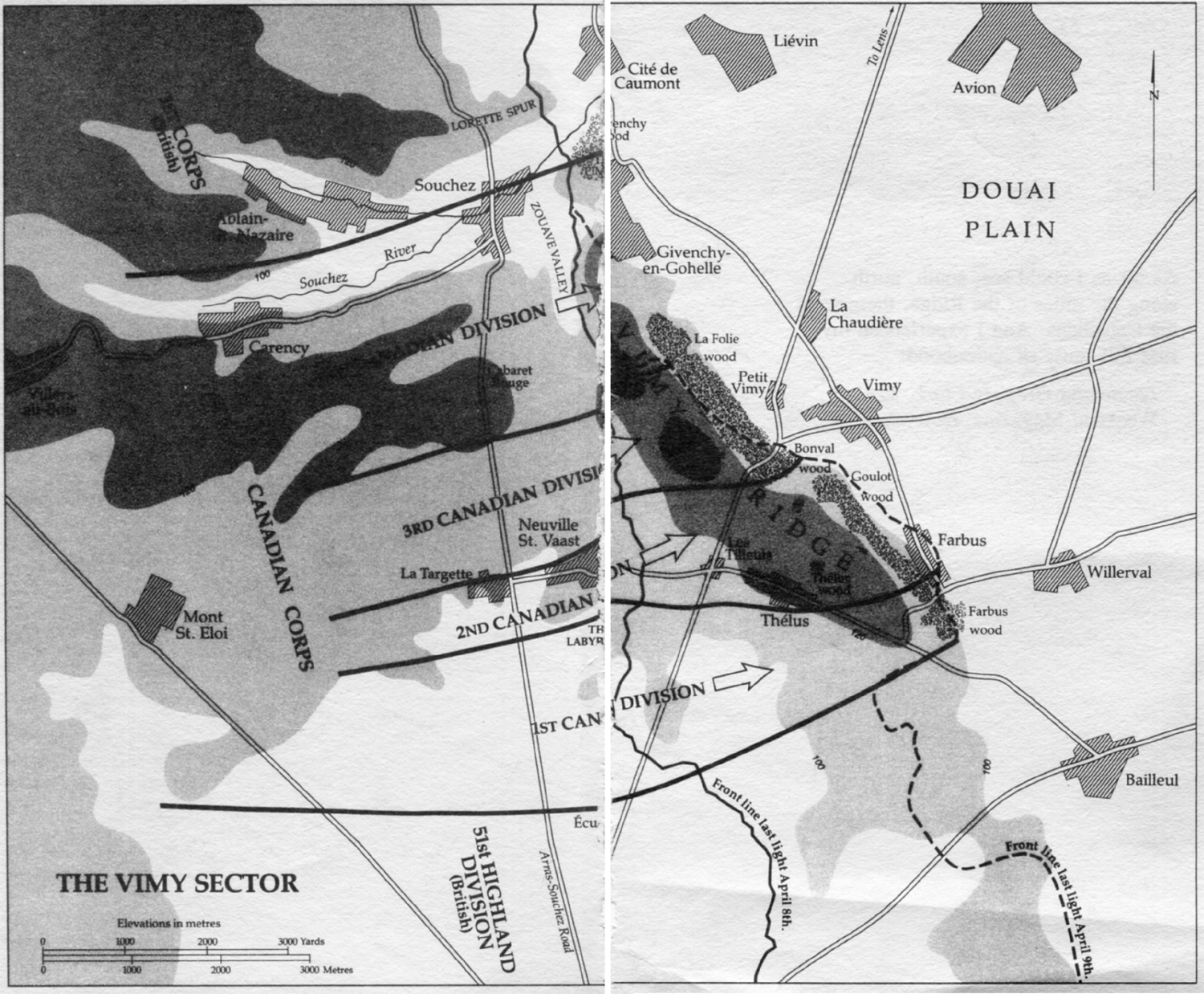

List of Maps

Maps by Geoffrey Matthews

Drawing of Vimy Ridge by Robert White

Overture: Ten Thousand Thunders

5:30 came and a great light lit the place, a light made up of innumerable flickering tongues, which appeared from the void and extended as far to the south as the eye could see, a light which rippled and lit the clouds in that moment of silence before the crash and thunder of the battle smote the senses. Then the Ridge in front was wreathed in flame as the shells burst, confining the Germans to their dugouts while our men advanced to the assault.

Private Lewis Duncan to his aunt Sarah, April 17, 1917

Ten Thousand Thunders

I t is probable that with the exception of the Krakatoa explosion of 1883, in all of history no human ears had ever been assaulted by the intensity of sound produced by the artillery barrage that launched the Battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917.

In the years that followed, the survivors would struggle to describe that shattering moment when 983 artillery pieces and 150 machine guns barked in unison to launch the first British victory in thirty-two months of frustrating warfare. All agreed that for anyone not present that dawn at Vimy it was not possible to comprehend the intensity of the experience. The shells and bullets hurtling above the trenches formed a canopy of red-hot steel just above the heads of the advancing troops-a canopy so dense that any Allied airplane flying too low exploded like a clay pigeon. At least four machines were destroyed that morning by their own guns.

The wall of sound, like ten thousand thunders, drowned out mens voices and smothered the skirl of the pipes the Highland regiments wistful homage to a more romantic era. It was as if a hundred express trains were roaring overhead. To Corporal Gus Sivertz, an optometrist from Victoria, the encompassing cocoon of sound was so palpable he felt that were he to raise a finger he would touch a solid ceiling. Individual noises, so familiar to the old soldiers at Vimy-the crump of naval guns, the bark and screech of the field artillery, the whine and clatter of the Vickers were lost in the over-powering cacophony of the great barrage. Tons of red-hot metal hurtling through the skies caused an artificial wind to spring up, intensifying the growing sleet storm slanting into the faces of the enemy.

The earth reverberated for miles around, as in an earthquake, and the faint booming of the guns was heard by David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, at Downing Street in London. Some men could scarcely bear the sound. Lewis Buck, a lumberman from the Ottawa Valley, deep in a dugout with his fellow stretcher-bearers, thought he would go crazy from the reverberations above his head. But then, he reasoned, this is what we came over for. Only the rats, he noticed, were unruffled by the noise.

The barrage began exactly at 5:30am. Technically, it was dawn, but the first streaks of light in the east were obliterated by the driving storm. Shivering in the cold, tense with expectation, their guts briefly warmed by a stiff tot of army rum, the men in the assault waves could scarcely see the great whaleback of Vimy Ridge, only a few hundred yards away. It angled off into the gloom its hump as high as a fifty-storey building-a miniature Gibraltar, honeycombed with German tunnels and dugouts, a labyrinth of steel and concrete fortifications, bristling with guns of every calibre.

The Germans had held and strengthened this fortress for more than two years and believed it to be impregnable. The French had hurled as many as twenty divisions against it and failed to take it. In three massive attacks between 1914 and 1916 they had squandered one hundred and fifty thousand poilus, dead or mangled. The British, who followed the French, had no better success. Now it was the Canadians turn.

They lay out in No Mans Land, twenty thousand young men of the first wave, stretched out along the four-mile front, crouching in the liquid gruel of the shallow assault trenches or flat on their bellies, noses in the mud, holding their breath for the moment of the assault. With the optimism of soldiers in every battle in every century, they did not expect to die, for death, in their minds, was a catastrophe visited upon others. Surely if they did as theyd been trained to do, if they hugged that advancing wall of shells-the famous creeping barrage they would survive the day.

Directly behind, ankle deep in water, greatcoats and put tees caked with mud, bayonets fixed, packstraps biting into their shoulders, a supporting wave of ten thousand more infantrymen blew on chilled fingers, puffed on hand-rolled fags, and fidgeted as they waited their turn to advance.

And behind them were seventy thousand more troops -gunners, stretcher-bearers, surgeons, cooks, transport drivers, mule-skinners, foresters, engineers, signalmen, runners, and brass hats all hived in a bewildering maze of tunnels, dugouts, sunken roads, and trenches that wriggled for more than two miles in a crazy-quilt pattern behind the front lines.

The Canadian Corps (which included one British brigade) faced an incredible challenge. In one day in fact in one morning these civilian volunteers from a small country with no military tradition were expected to do what the British and French had failed to do in two years. The timetable called for most of them to be on the crest of the ridge by noon. And they were expected to achieve that victory with fifty thousand fewer men than the French had lost in their own frustrated assaults.

Next page