As far as I could see, south, north along the miles of the Ridge, there were the Canadians. And I experienced my first full sense of nationhood.

Lieutenant Gregory Clark, M.C.

Weekend Magazine, November 13, 1967

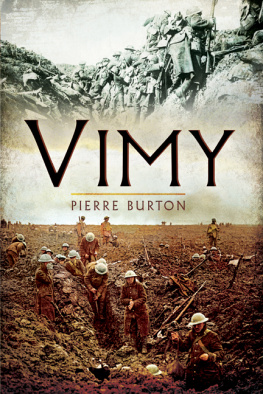

Copyright 1986 by Pierre Berton Enterprises Ltd.

Anchor Canada paperback edition 2001

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication, reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photoc opying, recording or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system without the prior written consent of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a license from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency is an infringement of the copyright law.

Anchor Canada and colophon are trademarks.

National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data

Berton, Pierre, 1920

Vimy

eISBN: 978-0-385-67361-7

1. Vimy Ridge, Battle of, 1917. 2. World War, 19141918

Campaigns France. 3. World War, 1914-1918 Canada. I. Title.

D545.V5B47 2001 940.431 C2001-930603-2

Published in Canada by

Anchor Canada, a division of

Random House of Canada Limited

Visit Random House of Canada Limiteds website:

www.randomhouse.ca

v3.1

Books by Pierre Berton

The Royal Family

The Mysterious North

Klondike

Just Add Water and Stir

Adventures of a Columnist

Fast Fast Fast Relief

The Big Sell

The Comfortable Pew

The Cool, Crazy, Committed World of the Sixties

The Smug Minority

The National Dream

The Last Spike

Drifting Home

Hollywoods Canada

My Country

The Dionne Years

The Wild Frontier

The Invasion of Canada

Flames Across the Border

Why We Act Like Canadians

The Promised Land

Vimy

Starting Out

The Arctic Grail

The Great Depression

Niagara: A History of the Falls

My Times: Living with History

1967, The Last Good Year

Picture Books

The New City (with Henri Rossier)

Remember Yesterday

The Great Railway

The Klondike Quest

Pierre Bertons Picture Book of Niagara Falls

Winter

The Great Lakes

Seacoasts

Pierre Bertons Canada

Anthologies

Great Canadians

Pierre and Janet Bertons Canadian Food Guide

Historic Headlines

Farewell to the Twentieth Century

Worth Repeating

Welcome to the Twenty-first Century

Fiction

Masquerade (pseudonym Lisa Kroniuk)

Books for Young Readers

The Golden Trail

The Secret World of Og

Adventures in Canadian History (22 volumes)

Contents

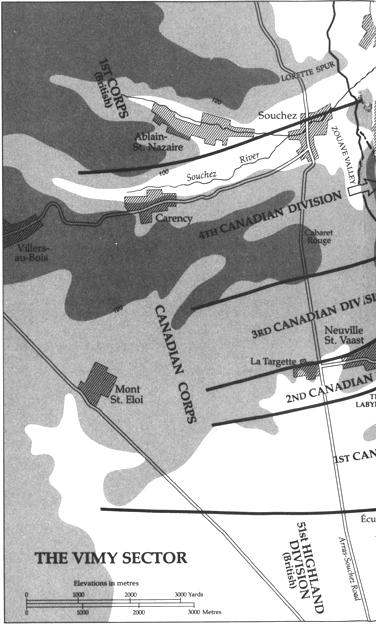

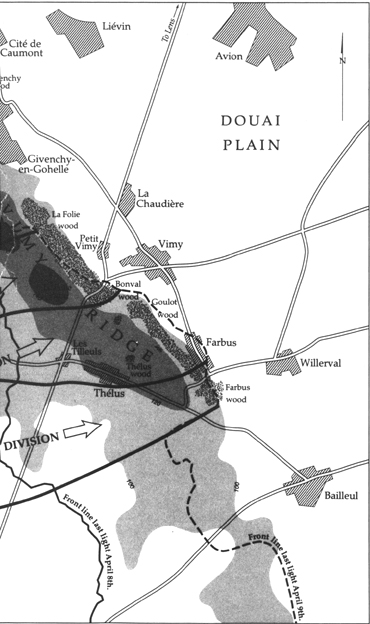

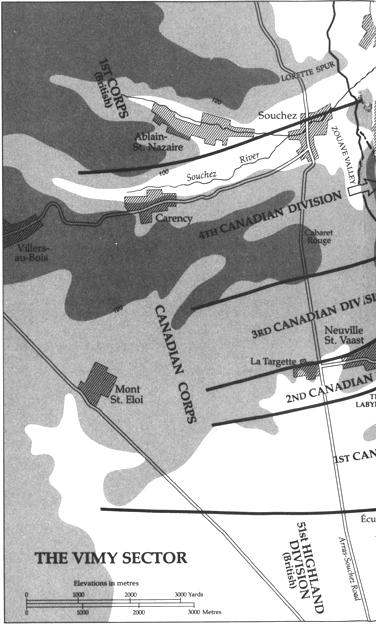

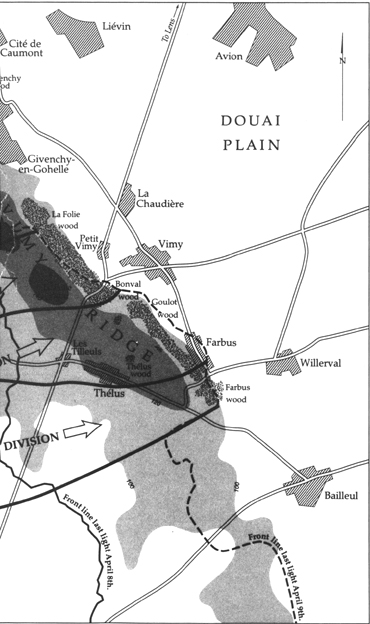

List of Maps

Maps by Geoffrey Matthews

Drawing of Vimy Ridge by Robert White

OVERTURE

Ten Thousand Thunders

5:30 came and a great light lit the place, a light made up of innumerable flickering tongues, which appeared from the void and extended as far to the south as the eye could see, a light which rippled and lit the clouds in that moment of silence before the crash and thunder of the battle smote the senses. Then the Ridge in front was wreathed in flame as the shells burst, confining the Germans to their dugouts while our men advanced to the assault.

Private Lewis Duncan to his aunt Sarah,

April 17, 1917

Ten Thousand Thunders

It is probable that with the exception of the Krakatoa explosion of 1883, in all of history no human ears had ever been assaulted by the intensity of sound produced by the artillery barrage that launched the Battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917.

In the years that followed, the survivors would struggle to describe that shattering moment when 983 artillery pieces and 150 machine guns barked in unison to launch the first British victory in thirty-two months of frustrating warfare. All agreed that for anyone not present that dawn at Vimy it was not possible to comprehend the intensity of the experience. The shells and bullets hurtling above the trenches formed a canopy of red-hot steel just above the heads of the advancing troops-a canopy so dense that any Allied airplane flying too low exploded like a clay pigeon. At least four machines were destroyed that morning by their own guns.

The wall of sound, like ten thousand thunders, drowned out mens voices and smothered the skirl of the pipes-the Highland regiments wistful homage to a more romantic era. It was as if a hundred express trains were roaring overhead. To Corporal Gus Sivertz, an optometrist from Victoria, the encompassing cocoon of sound was so palpable he felt that were he to raise a finger he would touch a solid ceiling. Individual noises, so familiar to the old soldiers at Vimy-the crump of naval guns, the bark and screech of the field artillery, the whine and clatter of the Vickers were lost in the overpowering cacophony of the great barrage. Tons of red-hot metal hurtling through the skies caused an artificial wind to spring up, intensifying the growing sleet storm slanting into the faces of the enemy.

The earth reverberated for miles around, as in an earthquake, and the faint booming of the guns was heard by David Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister, at Downing Street in London. Some men could scarcely bear the sound. Lewis Buck, a lumberman from the Ottawa Valley, deep in a dugout with his fellow stretcher-bearers, thought he would go crazy from the reverberations above his head. But then, he reasoned, this is what we came over for. Only the rats, he noticed, were unruffled by the noise.

The barrage began exactly at 5:30 A.M . Technically, it was dawn, but the first streaks of light in the east were obliterated by the driving storm. Shivering in the cold, tense with expectation, their guts briefly warmed by a stiff tot of army rum, the men in the assault waves could scarcely see the great whaleback of Vimy Ridge, only a few hundred yards away. It angled off into the gloom-its hump as high as a fifty-storey building-a miniature Gibraltar, honeycombed with German tunnels and dugouts, a labyrinth of steel and concrete fortifications, bristling with guns of every calibre.

The Germans had held and strengthened this fortress for more than two years and believed it to be impregnable. The French had hurled as many as twenty divisions against it and failed to take it. In three massive attacks between 1914 and 1916 they had squandered one hundred and fifty thousand poilus, dead or mangled. The British, who followed the French, had no better success. Now it was the Canadians turn.

They lay out in No Mans Land, twenty thousand young men of the first wave, stretched out along the four-mile front, crouching in the liquid gruel of the shallow assault trenches or flat on their bellies, noses in the mud, holding their breath for the moment of the assault. With the optimism of soldiers in every battle in every century, they did not expect to die, for death, in their minds, was a catastrophe visited upon others. Surely if they did as theyd been trained to do, if they hugged that advancing wall of shells-the famous creeping barrage they would survive the day.