This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1958 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

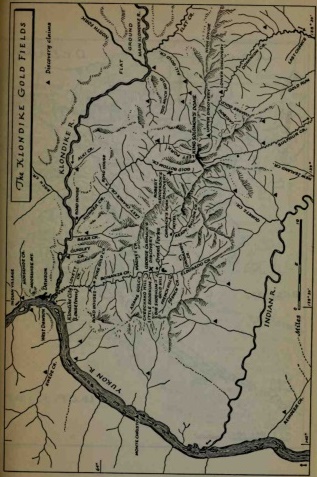

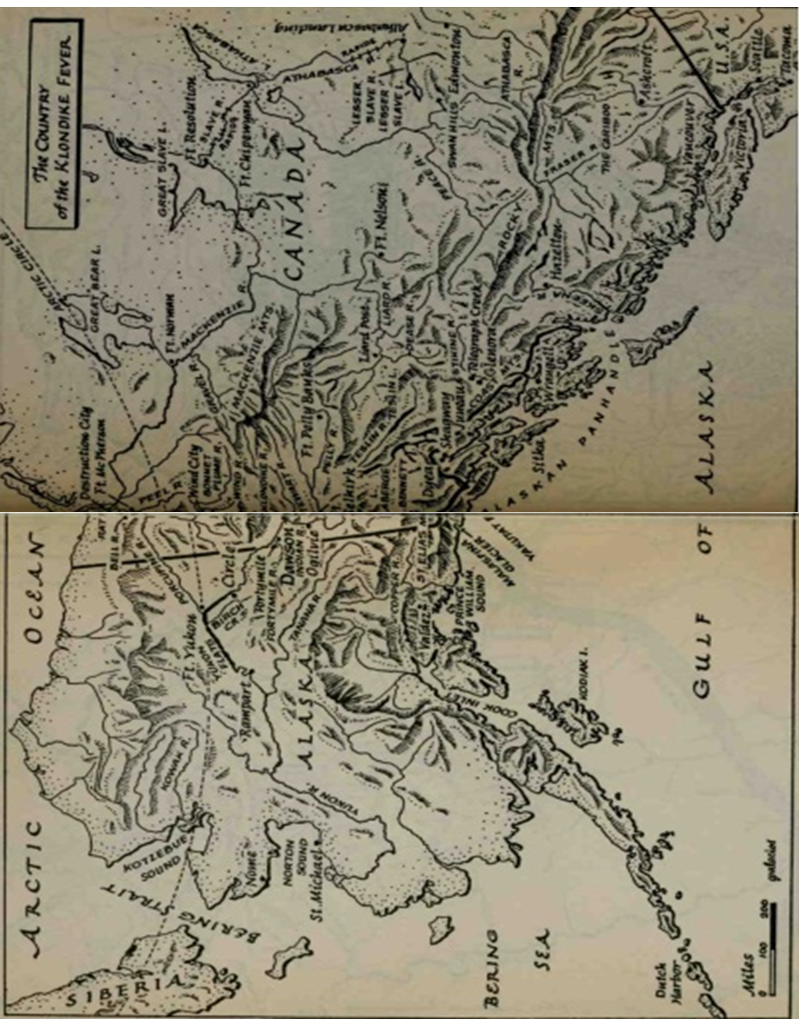

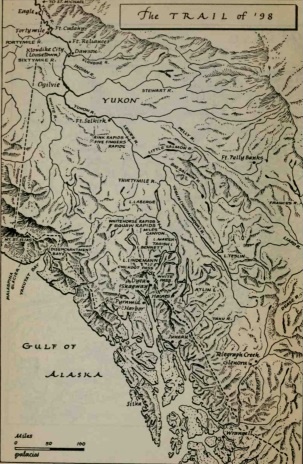

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

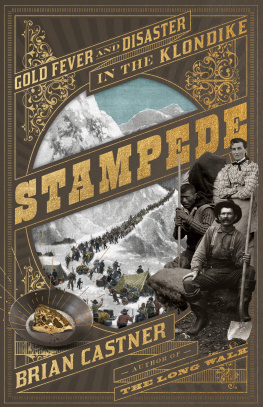

THE KLONDIKE FEVER: THE LIFE AND DEATH OF THE LAST GREAT GOLD RUSH

BY

PIERRE BERTON

DEDICATION

To my father,

Who crossed his Chilkoot in 1898,

and to my son,

who has yet to cross his

All the names mentioned in this narrative are real names.

All the events here listed actually occurred; nothing has been invented. All the speech is reproduced, to the best of the authors knowledge, as it was actually spoken.

All my life, he said, I have searched

for the treasure. I have sought it in the high

places, and in the narrow. I have

sought it in deep jungles, and at the ends

of rivers, and in dark cavernsand

yet have not found it.

Instead, at the end of every trail,

I have found you awaiting me. And now

You have become familiar to

me, though I cannot say I know you

well. Who are you?:

And the stranger answered: Thyself.

From an old tale

PRELUDE

We are the Pilgrims, master; we shall go

Always a little further: it may be

Beyond that last blue mountain barred with snow,

Across that angry or that glimmering sea.

White on a throne or guarded in a cave

There lives a prophet who can understand

Why men were born: but surely we are brave

Who take the Golden Road to Samarkand.

James Elroy Flecker: Hassan

1

It was the river that fashioned the land, and the river that ground down the gold.

Long before natives or white men saw it, the river was there, flowing for two thousand miles from mountain to seacoast, working its slow sculpture on valley and hillside, nibbling away at the flat tableland heaved up by the earths inner turmoils before the dawn of history.

The main stream had a thousand tentacles, and these reached back to the very spine of the continent, honing down the mountainsides into gullies and cleftsboulder grating on boulder, gravel grinding against gravel, sand scouring sand, until the river was glutted with silt and the whole Alaska-Yukon peninsula was pitted and grooved by the action of running water.

No mass could withstand this ceaseless abrasion, which lasted for more than five million years. The rocks and metals that had boiled up through fissures in the earths crust succumbed to it and were shaved and chiseled away. Quartz and feldspar, granite and limestone were reduced to muds and clays to be borne off with the current toward the sea, and even the veins of gold that streaked the mountain cores were sandpapered into dust and flour.

But the gold did not reach the sea, for its specific gravity is nineteen times that of water. The finest gold was carried lightly on the crest of the mountain torrents until it reached the more leisurely river, where it sank and was caught in the sandbars at the mouths of the tributary streams. The coarser gold moved for lesser distances: as soon as the pace of the current began to slacken, it was trapped in the crevices of bedrock where nothing could dislodge it. There it remained over the eons, concealed by a deepening blanket of muck, while the centuries rolled on and more gold was ground to dust, while the watercourses shifted and new gorges formed in the flat bottoms of old valleys, while the water gnawed deeper and deeper, and the pathways left by ancient streams turned the hillsides into graceful terraces.

Thus the gold lay scattered for the full length of the great Yukon River, on the hills and in the sandbars, in steep ravines and broad valleys, in subterranean channels of white gravel and glistening beds of black sand, in clefts thirty feet beneath the mosses and on outcroppings poking from the grasses high up on the benchland.

There was gold on a dozen tributary rivers and a hundred creeks which would remain nameless and unexplored until the gold was found; taken together, they drained three hundred and thirty thousand miles, stretching from British Columbia to the Bering Sea. There was gold on Atlin Lake at the very head of the Yukon River, and there was gold more than two thousand miles to the northwest in the glittering sands of the beach on Norton Sound into which the same river empties. There was gold on the Pelly and the Big Salmon and the Stewart, majestic watercourses that spill down from the Mackenzie Mountains of Canada to the east, and there was gold on the great Tanana, which rises in the Alaska Range on the southwest. There was gold in between these points at Minook and at Birch Creek and on the frothing Fortymile.

Yet, compared with a wretched little salmon stream and its handful of scrawny creeks, these noble rivers meant little. For in the Klondike Valley gold lay more thickly than on any other creek, river, pup, or sandbar in the whole of the Yukon watershedso thickly, indeed, that a single shovelful of paydirt could yield eight hundred dollars worth of dust and nuggets. But white men sought gold along the Yukon for a generation before they found it.

2

The Russians were the first on the river, in 1834, but they cared not a hoot for gold; no more than the natives who had given the river its name of Yukon, meaning The Greatest. Even before the river was discovered, whispers of gold in Russian America had reached the ears of Alexander Baranov, the rum-swilling Lord of Alaska, who ruled the peninsula from the island bastion of Sitka. But Baranov, garnering a fortune in furs for his Czarist masters against an incongruous background of fine books, costly paintings, and brilliantly plumaged officers and women, was not anxious for a gold rush. When one of the Russians babbled drunkenly of gold, so legend has it, the Lord of Alaska ordered him shot.