Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

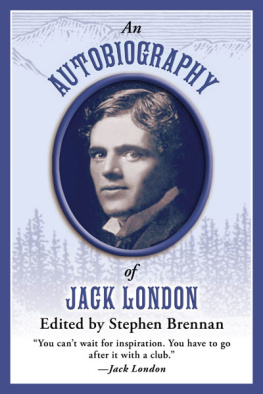

It was in the Klondike I found myself. There nobody talks. Everybody thinks. You get your true perspective. I got mine.

JACK LONDON

He was an adventurer and man of action as few writers have ever been.

GEORGE ORWELL

He was a fighter. He was a terrific competitor. He wanted to win whatever he did. At the same time, while he was physically tough, he was emotionally sensitive. He could cry over the death of his favorite animal, or over the tragic episode in a novel.

EARLE LABOR

BIOGRAPHER AND CURATOR

JACK LONDON MUSEUM

SHREVEPORT, LOUISIANA

To David Neufeld, Earle Labor, and Dawne Mitchell, without whom I never would have written this book. And a special thank-you to Karl Gurcke, as well as Whit Bond, the grandson of Stampeder Louis Bond, who befriended Jack London when he arrived in Dawson.

Thank you also to Steve Shaffer, Jack Londons step-great-nephew, who, with his cousin Brian Shepard, now manages Jacks ranch and vineyards in Glen Ellen, California.

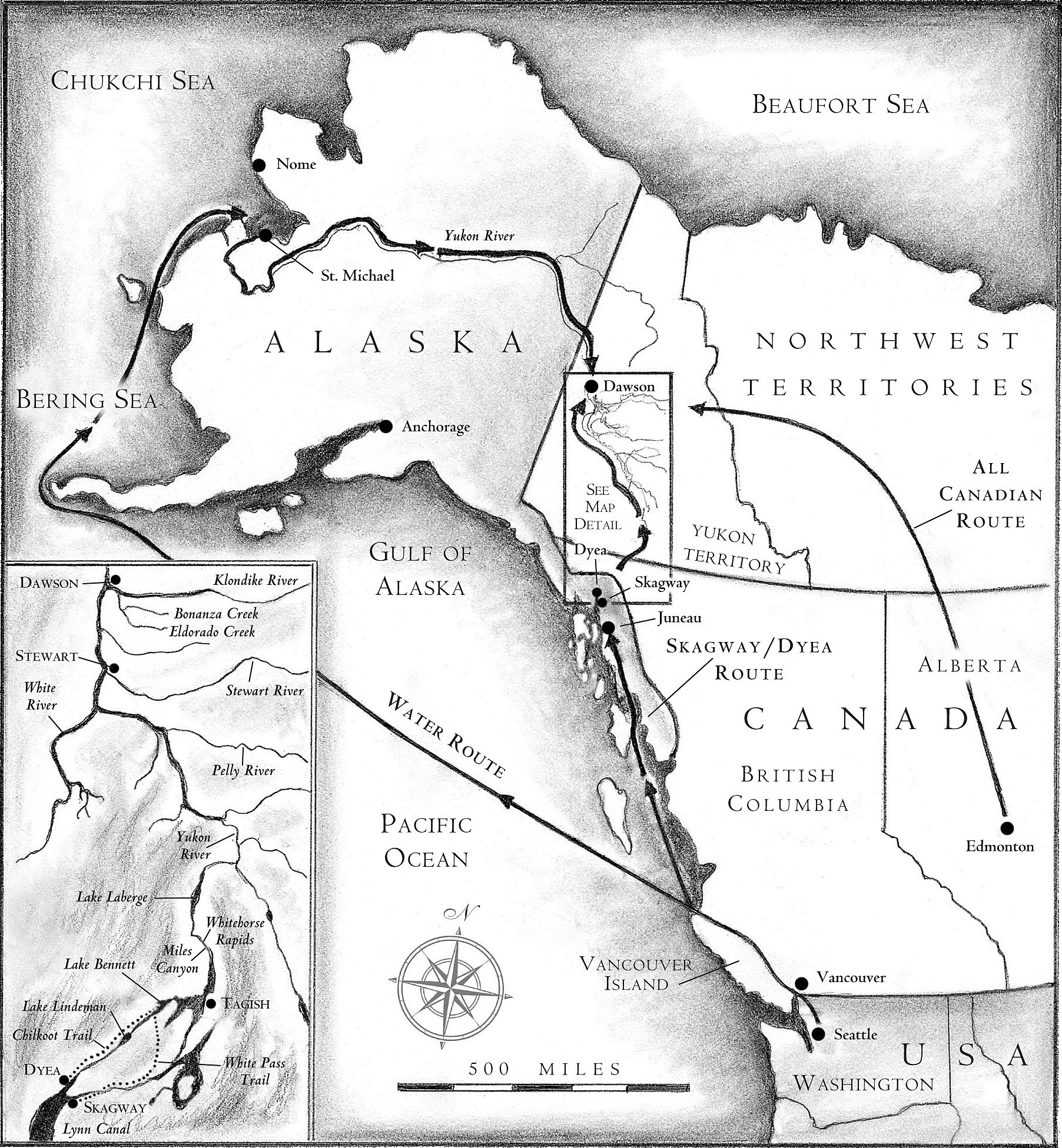

Jack London headed north to strike it rich in the Klondike. At twenty-one he was among the hundreds of thousands of Stampeders, as they came to be known, who left their dull and dreary lives all over the globe in order to make a dangerous journey into the heart of Canadas Yukon Territory. Between 1896 and 1899, forty thousand gold seekers, after months of grueling travel, arrived in the gold-rush town of Dawson on the banks of the Klondike and Yukon Rivers. A mere four thousand would actually strike gold.

Jack had decided very early on that he wanted to be a writer. He loved books, was good at writing, and desperately wanted to escape the hard work of his poor childhood. If he could strike it rich, Jack would devote his life to being an author. That was his dream.

During Jack Londons time, the United States was gripped in an economic depression, and jobs were scarce. Although the typical wage was only ten cents an hour, Jack was not afraid of hard work. In order to make money for his struggling family in Oakland, Californiaacross the bay from San Franciscohe had labored with his hands from the age of six. He helped his father grow vegetables to sell. At eleven he ran two paper routes, one before and one after school. He was up by three in the morning every day, and on weekends he worked in the bowling alley, setting up pins. When Jack was fourteen, he spent ten hours a day canning pickles to bring home a dollar. Once, he worked in the cannery for thirty-six hours straight.

Lack of money forced him to drop out after only one semester at the University of California at Berkeley, and he got a job working in a laundry shop. He always wrote in his spare time and vowed to himself hed write at least one thousand words a dayfour typed, double-spaced pages. Writing steadily for the next twenty years, he would manage to produce more than two hundred short stories, as well as scores of novels and works of nonfiction. When he died at the age of forty, he had written more than fifty books, an output far greater than most writers.

From his early travels to the Klondike, Jack brought back the precious seeds of tales that bloomed into famous novels, such as White Fang and The Call of the Wild , and short stories, including To Build a Fire and The White Silence. Many believe his greatest works come from his experiences on that Klondike journey of 189798narratives set in the Yukon wilderness.

Although he found little gold in the creeks, Jack London nevertheless became the first American writer of the twentieth century to earn a million dollars from his writing. He died one of the worlds most famous writers.

This is the story of Jack Londons journey in the gold fields of the Klondikeand what he discovered there.

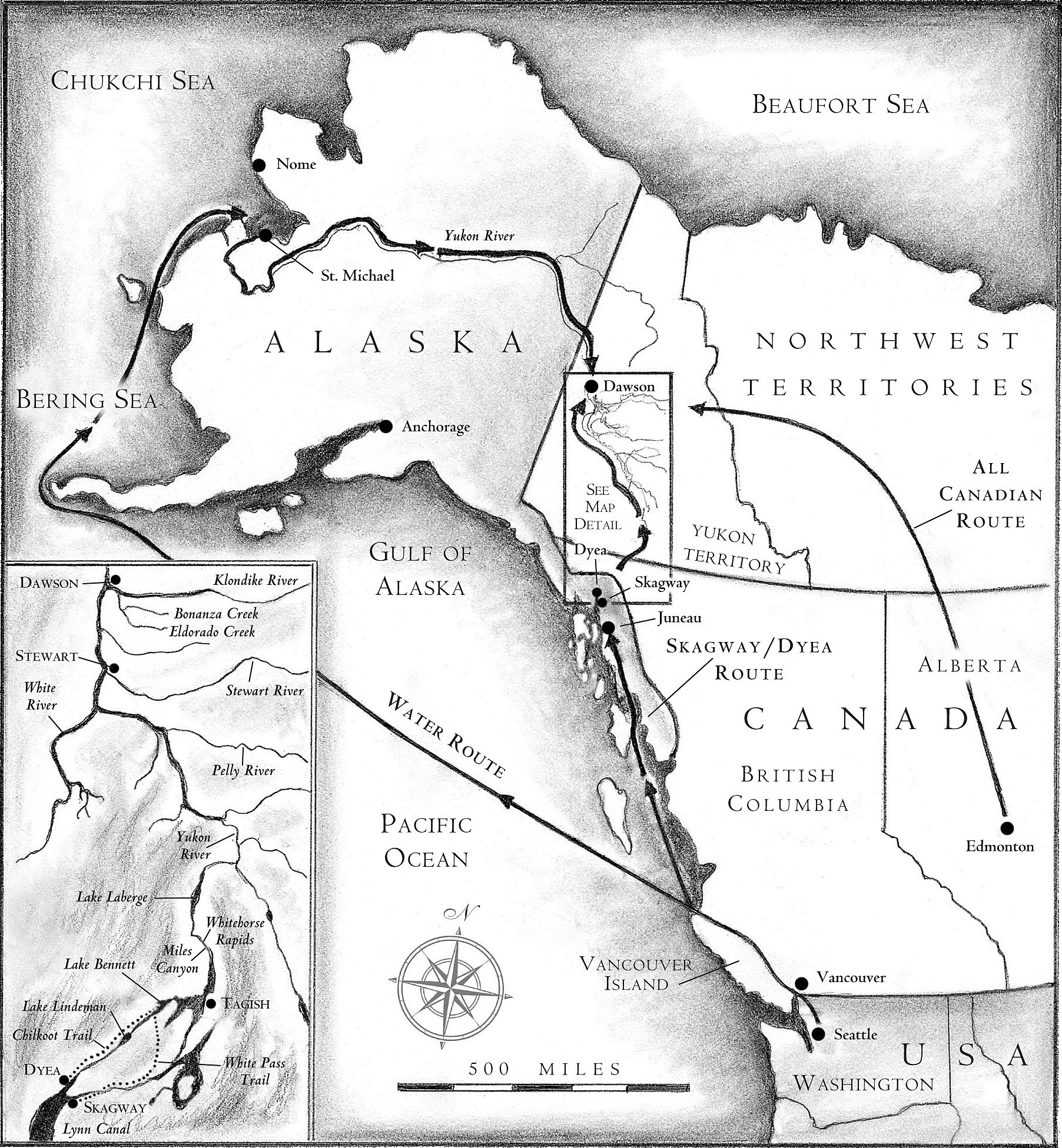

TRAVEL ROUTES TO

THE KLONDIKE

The mudflats at Dyea during the Stampede

(University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections, Hegg 54)

IN A HEAVY DRIZZLE, Jack London and his gold-mining partners sat in dugout canoes loaded with five tons of supplies as Sitka Tlingit paddlers drove their seventy-five-foot-long boats through heavy seas. Clouds tumbled like ghosts over the craggy peaks above them. Jack had traveled a long wayfirst by steamer from San Francisco, California, to Juneau, Alaska, and now by wooden canoe to the coastal village of Dyea (pronounced Die-EE), Alaska, one hundred miles north of Juneau. Formerly a small Tlingit settlement, Dyea had become a raucous boomtown of wooden and canvas shanties with tenderfoot miners trying to get organized for a trek over the Coast Mountains to look for gold.

Under the scowling gray sky, wide-beamed sailing dinghies and flat-bottomed craft ran men and cargo from steamers anchored a few miles offshore to the wide mudflats at Dyea. Horses, cattle, and dogs were sometimes pitched overboard to swim to shore, where masses of freight and baggage were dumped like garbage in chaotic heaps.

When the two canoes hit ground on August 7, 1897, Jack and his partners, along with the Tlingit paddlers and their families, jumped into the icy water and pitched gear onto the flats.

With the seawater above his knees, Jack worked furiously. At five feet seven inches tall and weighing 160 pounds, Jack was fierce and muscular. He had to work fast because it was low tide, and soon the water would rise and sweep everything away. So the curly-haired, gray-eyed lad muscled his cargo out of the boat and then more than a mile down the flats to higher ground.

In order to separate his and his partners thousands of pounds of gear from the supplies of all the other miners, Jack strained under the weight of axes, shovels, pans, cold weather clothes, stoves, and tents, along with one-hundred-pound sacks of rice, flour, sugar, bacon, and, of course, endless cans or crates of tinned beans. Beans, bacon, and breadthe three Bswere the staples of the Stampeder, food that he and his partners would live on for a year while they hunted for gold in the Klondike.

On the beach, wild-eyed men desperately grabbed their gear and began to sort through everything. It was a crazy open-air warehouse. Everyone was in each others way, bumping and shoving and shouting. Jack heard loud curses against the sea wind. Dogs snarled and fought among their masters legs.

When he finished getting all his gear organized, Jack explored the makeshift settlement of fifteen hundred tents and crude wooden buildings crammed among the coastal scrub. He passed jerrybuilt stores selling food and supplies at exorbitantly high prices. He saw saloons where miners gambled and drank until they couldnt walk. He heard rowdy men shooting into the air just for the heck of it.