ACCLAIM FOR JENNIFER DUNCANS

F RONTIER S PIRIT

There is nothing dry or conventional about Jennifer Duncans perspective on the Klondike Gold Rush, one of Canadas most written about events. This engrossing portrait provides a fresh way to fall under the Yukons spell. It brings to life the previously uncelebrated women who forged fortunes, built businesses and lived scandalously in the punishing north. Duncans photo-illustrated tales of women from every walk of life are irreverent, boisterous and engaging, a find for those who love adventure.

The Hamilton Spectator

Jennifer Duncan is the sort of person youd like to meet around a campfire or at a cozy pub on a snowy nighta true woman of the Yukon, a woman who can tell a mean yarn. The stories are in the main straightforward, compelling, and fun. And just as a woman can survive the Yukon as well as any man, Duncan can tell a great Gold Rush story as well as any of the guys at the bar.

Quill & Quire

Duncans skill as a writer of fictionshe is a much-published poet and fictioneershines through the whole book, imbuing the story with compelling immediacy. Her appreciation of the women who have lived therepast and presentand the environment they endure is infectious.

National Post

This is the wonder of Duncans book: the way she weaves each of her characters in and out of the lives of the others. [Frontier Spirit is] both hilarious and touching.

New Brunswick Reader

A labour of love for the Yukon and the strong people who chose to live there. The love [Duncan] feels for Dawson City comes through in her words, and helps her give new life to her subjects.

Times-Colonist (Victoria)

A celebration of the independent spirit, these character studies of eight women adventurers, separately and together, embody the essence of the Klondike.

The Beaver

I long to speak out the intense inspiration that comes to me from the lives of strong women.

Any woman venturesome enough to join the Klondike Gold Rush was likely to be a handful, not at all content with being regarded as a fragile thing, all sighs and sweetness. Influenced by the feminist spirit of the times, she was ready to assert her rights as a human being equal if not superior to any male.

PREFACE

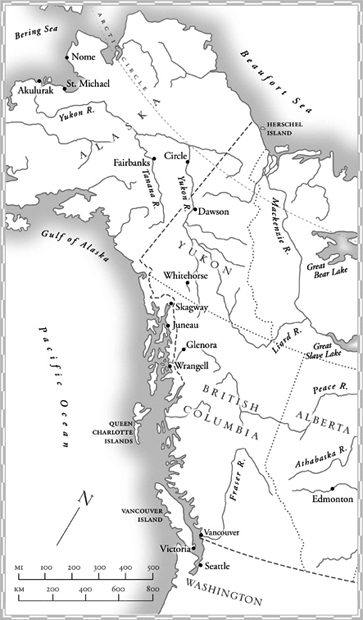

They say it is no place for a woman. They say many a man has turned back, defeated by the trail to the Klondike goldfields, its creeks to be forded, its waist-deep swamps to be waded through, its steep, treacherous mountains to be scaled. But there she is, a woman, African-American, 19 years old, and nine months pregnant, on the Stikine River Trail in the autumn of 1897. And she is not turning back.

After 150 miles, she goes into labour in a First Nations village. The Tagish people have seen many newcomers come pouring over the mountains, but never someone like her. Another kind of white, they call her.

She asks them what they call this lake. They say, Teslin. She tells them: This is what Ill call my daughter. For the lake where she was born. For you who have always lived here.

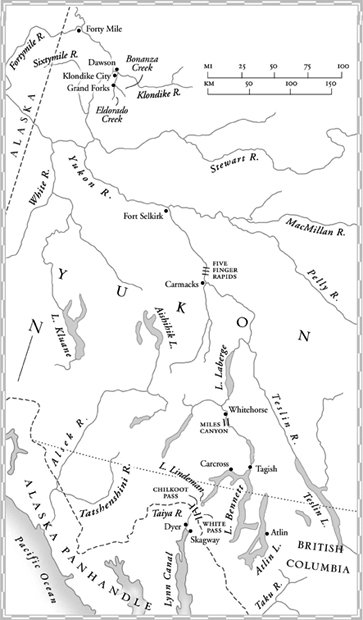

Lucille Hunter was one of many brave women who stampeded to the Gold Rush. Pausing briefly in Teslin to give birth, Lucille did not wait out the winter as most stampeders did but mushed on for weeks through frigid temperatures with her husband, Charles, their newborn daughter, and their dog team, finally reaching Dawson City on the brink of the new year. Her courage and stamina enabled the family to stake a Bonanza Creek claim before the spring hordes arrived by boat.

Lucilles strength only grew in this wild land. As a widow during the Depression, she would walk 140 miles between her silver mine in Mayo and her three gold mines in Dawson, running these operations single-handedly. After the Second World War, she ran a laundry in Whitehorse, where she died at 94, in 1972.

Like Lucille Hunter, many of the women of the Gold Rush are fascinating characters, with unusual claims to fame.

There were the wives of the first Klondike Kings, like Bride of the Klondike Ethel Berry, who spent her honeymoon crossing the Chilkoot Pass during the Gold Trickle, and whose arrival in Seattle in 1897 with $100,000 worth of gold in her bedroll fed the media frenzy that sparked the rush to the goldfields. With her sister Tot Bush, Ethel helped with cooking and panning on the claims that would innovate hydraulic mining methods in the Yukon, and she collected for herself $70,000 of gold nuggets, ending up a wealthy Beverly Hills widow.

There were eccentrics, like Royalist-socialist-feminist activist and poet Marie Joussaye Fotheringham from Belleville, Ontario. Marie had helped organize the Working Girls Union and had published a volume of her verse before arriving in Dawson, marrying an ex-RCMP officer, snapping up over 30 claims, and being sentenced to two months hard labour for stealing diamonds from another woman.

There were wealthy tourists Mary Hitchcock and Edith van Buren, who brought up an ice cream machine, a magic lantern, a zither, a mandolin, a bowling alley, a score of live pigeons, two canaries, a parrot, and two Great Dane dogs on their 1897 trip to Dawson.

There were notorious prostitutes like Mae Fields. Mae famously put a gun to her head after being abandoned by her husband. Thwarted by an onlooker, she still made the headlines for the attempt. Mae supplemented her income as an Orpheum dance hall girl with keeping a house of ill repute, for which she was finally put on trial in 1908.

The lives of women like Lucille Hunter, Ethel Berry, and Mae Fields have largely been sluiced from the popular mythology of the Gold Rush, and mining the nuggets that remain in the riffles is a painstaking task. Because what scanty material exists about these women has already been explored in previous works, I have chosen to focus on the women who have left the most full and interesting accounts of their lives. I wondered: What kind of woman was drawn to the Gold Rush? What were these womens lives like before and after the Gold Rush? How significant a part did the Gold Rush play in the broader continuum of these womens lives?