2

THE SIX-FOOT BURY

February 12, 1917Haillicourt, France It might have been his lack of attention in high school. Pos- sibly the declaration of war in the summer of 1914. But it was quite likely the words of encouragement from two recruiting sergeants who came to Lyman Nichollss home in Uxbridge, Onta- rio, that autumn. Theyd heard the fifteen-year-old had served as a bugler with the Boy Scouts and they needed one for their Mississauga Horse regiment in Toronto. However it was that Lyman got the bug to enlist, the spark happened on a June day in 1915.

We were having a French lesson, Nicholls said. Our teacher... Miss Topin went out of the classroom for a few minutes and I stood up and started for the window. I said, This is our chance, fellows, and climbed out the window. Seven others followed me.

The eight teenagers walked quicklythey actually walked in step as if marchingto the Uxbridge post office, which had been turned into a military recruiting office. All the boys took their medical exams, signed the enlistment papers, and then went to the quartermasters office to pick up their uniforms. They were told to report back to the recruiter the next morning at six oclock, when they would officially become members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force en route to fight overseas. By that time, however, most of the boys parents had intervened since they were all underage. Nevertheless, by his next birthday, his eighteenth, Lyman Nicholls had signed his legitimate attestation papers and joined the brand-new 116th Battalion.

It was difficult to avoid the recruitment euphoria sweeping that southern Ontario township. It had begun in 1915, when Ottawa contacted local professional and high-profile personality Samuel S. Sharpe. Born on a farm north of Uxbridge in 1873, Sam and his family had moved into town a few years later, when his father took a job operating the Joseph Gould Mansion House Hotel. Once the Sharpe son had received his education locally, he attended law school in Toronto and then returned home to establish the Uxbridge law firm of Patterson and Sharpe. Hed then served as town solicitor for ten years, married Goulds granddaughter, Mabel Crosby, and by 1908 had become the elected Conservative Member of Parliament rep- resenting the county. In the autumn of 1915, the Canadian Army searched for the right individual to raise a volunteer military unit in south-central Ontario for overseas service. On November 9, Sharpe became the first lieutenant-colonel of the 116th Ontario County Battalion with headquarters in Uxbridge.

Overnight, the recruiting and training of a full battalion, about 1,000 men, transformed the sleepy valley village of Uxbridge, northeast of Toronto, into a thriving military centre. Sharpes recruiting speeches, posters, and published editorials attracted men from all professions and trades in town and from surrounding communities, including Argyle, Atherley, Beaverton, Cannington, Sebright, Sun-derland, and Woodville. Uxbridge town fathers faced a sudden population explosion and responded by providing impromptu sleeping quarters and billeting in private homes. Each day that fall a sandy farm field just south of town became the focal point of the battalion, as recruits sprawled on buttslong lines of mounded earthand fired round after round from their Ross rifles into steel-framed targets several hundred yards away. Young Gordon King and his chumsen route to poaching trout at the local Fish and Game Clubs pond stopped to take in the art and science of army marksmanship. During the following spring of 1916 the 116th even conducted drill demonstrations at Elgin Park, in downtown Uxbridge.

Then a company was formed up on a field east of the post office, King wrote. Only five or six at the time, Gordon became swept up in the military fervor too; he wore a khaki uniform, complete with corporals stripes and unit cap badge that his mother had made for him. The men fired a salute... as they marched to the train en route to war.

As part of their formal send-off, Uxbridge residents erected arches and banners over downtown streets with religious and patriotic slo-gans, including God bless our splendid men. Send them safe home again. The Junior Relief Club participated by presenting the battalions standards to the departing troops. Men of the Ontario counties battalion then travelled east to Port Perry, south to Whitby, by boat across Lake Ontario to Niagara, and overseas to Britain in July 1916. That fall, at Bramshott Camp in England, the Canadian volunteers further trained for their posting to the front lines. Then, as a final act of allegiance, the battalion ceremoniously deposited its regimental colours at Westminster Abbey and departed for France.

In the time it had taken Lt.-Col. Sam Sharpe to recruit, train, transport, and deliver his 116th Battalion to the front lines in France, much had happened to the Canadian war effort. The 1st Division had joined the British Army and withstood the first gas attack at Ypres in the spring of 1915. The 2nd and 3rd Divisions had been organized, trained, and shipped to England also that year, the 4th Division in the new year. By January 1916, there were 50,000 Canadians in the field. The armys weapon of choice was no longer the Ross rifle, but the Lee Enfield. The Canadian Corps had added Festubert, St. Eloi, Mount Sorrel, the Somme, and Courcelette to its battle honours. And the controversial Col. Sam Hughes, once popular Minister of Militia and therefore strong supporter of citizen soldiers in the Canadian Army, had been fired from his cabinet portfolio, allowing a changing of the guard at the top of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

On February 12, 1917, Sam Sharpes Ontario County Battalion, dubbed the baby battalion by other members of the Canadian Corps, had arrived at rest billets in the village of Haillicourt, about twelve miles from the fighting. Throughout that first day the battalion soldiers could hear the guns exchanging volleys over Vimy Ridge. Each man, wrote the adjutant, had nothing but an ardent desire to get through the baptism of fire with as much glory and as few casualties as possible.

That hope was quickly dashed. No sooner had Lt.-Col. Sharpe begun settling his battalion billeted in a frame barn just behind the front lines, when he had to send his first note of condolence home. Pte. George Hudges, a battalion signaller who had earlier been drafted into a sister regiment, lost both his arms during a German shelling and died shortly after. Sharpe reported that Hudges, a smart and gentlemanly young man, had become the 116ths first casualty of the war. Along with that grim task, like any newly arrived officer at the front, Lt.-Col. Sharpe immediately received a reconnaissance tour of the war zone in general and background notes on the military significance of Vimy Ridge in particular.

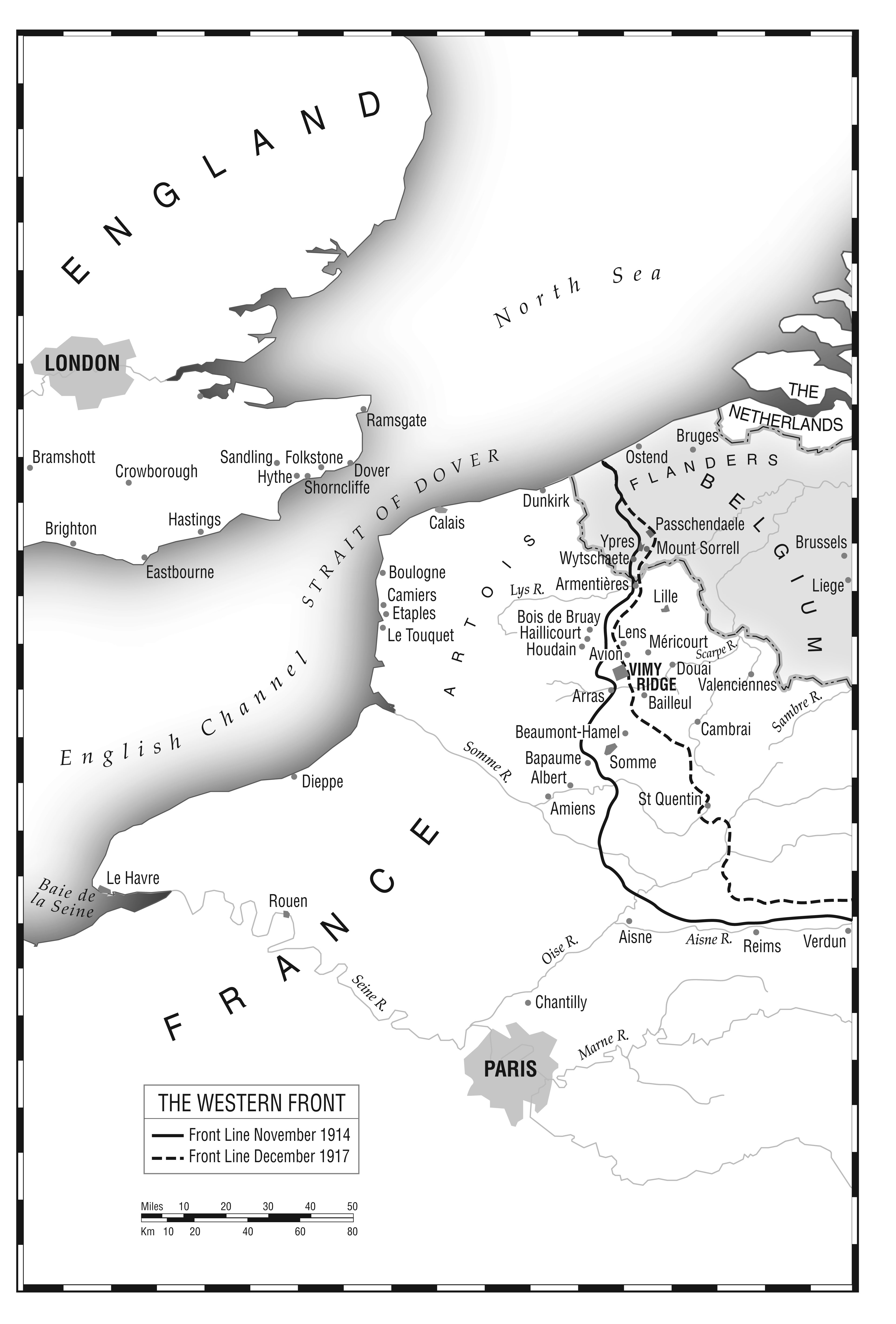

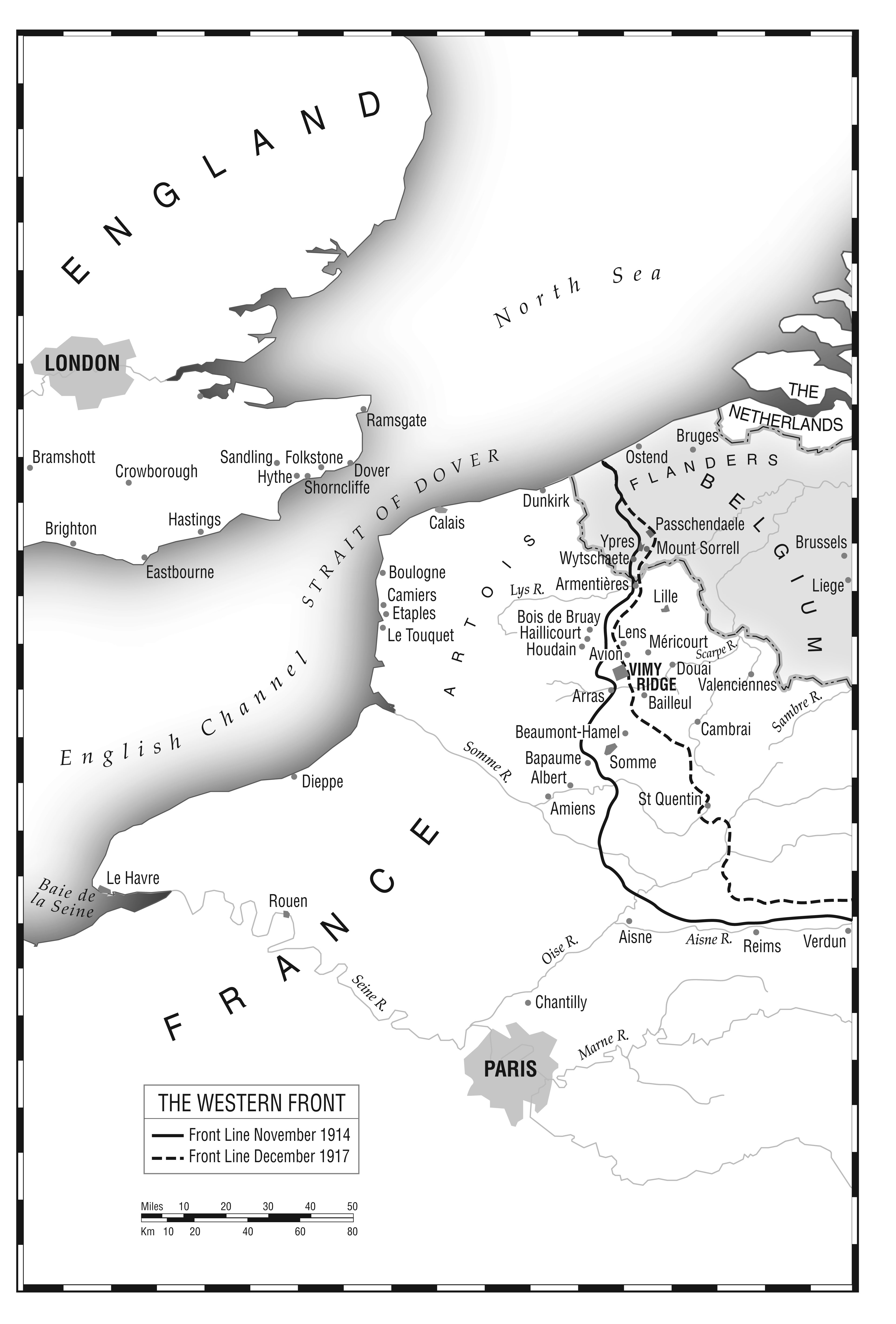

By the time Sharpe and the 116th arrived on the scene, the third winter of the Great War had settled very little on the Western Front. Bookended by the North Sea in the northwest and the Swiss Alps in the southeast, more than 300 miles of front-line battleground stretched diagonally across western Europe. Entrenched along its length and on either side of a No Mans Land buffer zonevarying in width from several farm fields to less than a football fieldthe two adversaries had shelled, gassed, mined, attacked, and counterattacked each other to a stalemate.

Since the outbreak of war in August 1914, several geographic and topographic sites along the Western Front had emerged as strategic positions. Chief among them on the Douai Plain between the Rivers Souchez and Scarpe in north-central France was Vimy Ridge. A prominent heightnine miles long between the towns of Givenchy-en-Gohelle in the northwest and Bailleul to the southeastthe humpbacked ridge offered a most favourable fortress for any army occupying it. The northern end and the escarpment rose abruptly from the Souchez ravineabout 200 feet in half a mileand included the summit known as the Pimple, while to the southeast the main