Passchendaele by Philip Warner

The Story Behind the Tragic Victory of 1917

Index of Contents

Chapter 1 It Must Come to a Fight

Chapter 2 -The Cockpit of Europe

Chapter 3 The Preliminary Rounds

Chapter 4 The Mines at Messines

Chapter 5 Everywhere Successful

Chapter 6 Did We Really Send Men to Fight in This?

Chapter 7 See You Again in Hell

Chapter 8 The Difficulties Were Greatly Underestimated

Chapter 9 The Focus of a Spiders Web

Chapter 10 The Supporters

Chapter 11 The Other Side of the Hill

Chapter 12 The View from the Trenches

Chapter 13 Hindsight

Chapter 14 Visiting the Battlefield Today

Select Bibliography

Acknowledgements

Picture Gallery

Philip Warner A Short Biography

Philip Warner A Select Bibliography

Chapter 1

It Must Come to a Fight

Passchendaele is a small Belgian village, but it is also the name given to one of the most gruelling, bloody and bizarre battles of the First World War. The village itself was eventually captured by the Canadian 2nd Division, but before that happened approximately half a million men British, French, Canadians, Australians, New Zealanders and, by no means least, Germans had become casualties*1. It is not merely the number of deaths which makes that battle in the autumn of 1917 unique in the history of warfare it is the almost unimaginable horror of the circumstances. That men could survive such an experience and remain sane is, perhaps, even more astonishing than the death toll. On the Allied side 90,000 men were reported missing, which on this occasion was an official acknowledgement that they had been blown to unrecognizable fragments, drowned or suffocated in liquid mud. Usually the remains of a body can be identified by the tag worn on a cord round every soldiers neck. There are two discs: one red, one green. Each is marked with the name, religion and number of the soldier. When he is killed, one disc is taken and sent to records, while the other stays with the body so that it may be identified when that body is later re-interred in a war cemetery. This is the way in which missing men, previously thought to have been killed, are identified. But at Passchendaele there was no trace of either bodies or ID tags of thousand upon thousand.

The Germans thought that Passchendaele was their worst battle of the war worse, in fact, than Verdun, and Verdun was bad enough. Kuhl, the German historian and a former Chief of the German General Staff, wrote:

The sufferings, privations and exertions which the soldiers had to bear were inexpressible. Terrible was the spiritual burden on the lonely man in the shell hole, and terrible the strain on the nerves during the bombardments which continued day and night. The Hell of Verdun was exceeded by Flanders. The Battle of Flanders [the German name for Passchendaele] has been called The greatest martyrdom of the World War.

No division could last more than a fortnight in this hell. Then it had to be relieved by new troops. Looking back it seems that what was borne here was superhuman. With respect and thankfulness the German people will always remember the heroes of Flanders.

There is a reason behind every battle, however illogical in retrospect that reason may seem. The Battle of Passchendaele was inevitable in the strategic and tactical context of the First World War. It was not, however, an isolated battle, nor even the last of a series of battles. It took place in an area which in the past had known other bloody conflicts, an area whose geographical situation made battles for key points almost unavoidable, but what made Passchendaele so appalling was that it was fought when the weather made it almost but not quite impossible. If those who directed it had known the conditions in which Passchendaele would be fought, it is unlikely though one cannot be certain of this that they would have embarked on it. It is said that Kiggell, Haigs Chief of Staff, wept. When he eventually reached the mere edge of the battlefield, and exclaimed, Did we really send men to fight in this?

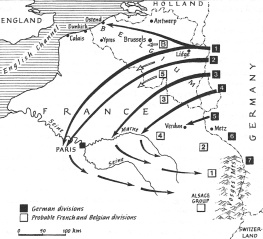

Seventy years later the events which eventually led to Passchendaele have become clearer, and the battles origins can be seen to go back a long way. They are also the origins of the First World War, and it is necessary to examine them in order to grasp the feelings of frustration on both sides which made the battle take the course it did. Those events started with Bismarcks successful campaign for the transformation of Germany, under Prussian leadership, from a collection of independent states into a modern industrial power, complete with colonies to provide both raw materials and outlets for manufactured goods. It had begun with Prussias war against Denmark, which was won within three months in 1864. Prussia fought another tidy little war with Austria in 1866, all finished within six weeks; and a slightly longer one with France in 1870, but that too was over in six months. However these, Bismarck and his successors realized, were only interim wars. France, caught in a weak moment, had been defeated, but it had learnt its lesson and would not be so easily dealt with next time. There remained Russia and, of course, Great Britain. Russia blocked German expansion to the east, while France and Britain prevented any movement into the Mediterranean region.

By 1914 Germany had made considerable progress with the formation of a colonial empire, but it was obvious that she had come into the field late and had only acquired the less desirable colonies, the territories which other countries felt they could spare. The rich prizes, like India, West Africa, Indo-China and the East Indies, were firmly in British, French or Dutch hands. Even Belgium, with the best part of the Congo in her grasp, was in a better position than Germany. Efforts to gain a foothold in the Mediterranean were blocked in Morocco in 1911,*2 even though Germany did gain a few thousand miles of virtually useless territory in the Congo in compensation. But before this occurred Germany had decided that the only way to challenge her rivals was by building an impressive navy.

British policy at the time was to maintain a navy equal to any two others in the world, so the German task would not be easy. Attempts had been made at the Hague conferences*3 to limit the arms race, which was an obvious danger to peace, but the conferences achieved nothing concrete and could only try to humanize war when it began. From this came agreements not to bomb unfortified towns, and that prisoners-of-war would be treated with some consideration: they were not invariably observed.

Even so, the Great Powers might have continued for years without coming to blows had there not been a detonator in what was known as the Balkans. The term Balkans has now slipped into disuse, but in the early part of the twentieth century it often cropped up in conversation as symbolizing the potential dangers which arise when a strategically important area is occupied by a number of small, highly antagonistic, unstable states. Those states were Greece, Turkey, Bulgaria, Albania, Romania, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, the last two of which are now incorporated into Yugoslavia. Most of these small states had been broken away from the decaying Turkish Empire in the previous century, and one, Serbia, had ambitions to build a Greater Serbia. Russia liked to pose as the patron of small Slav states such as Serbia which were struggling to establish their independence, but in fact her motives were less benevolent than calculating: she hoped to use such states in her attempt to obtain access to the Mediterranean. However, after the 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the deposition of the Sultan Abdul Hamid the Turkish Empire temporarily stopped crumbling and its new, more efficient government was not likely to look kindly on Russian attempts to expand in this area. A somewhat nervous spectator of all this was Austria-Hungary, an ancient, also crumbling, empire which sprawled across southern Europe with a multitude of different peoples under its uncertain control. Among its indigestible elements were a number of Serbs which Serbia itself hoped to use in its plans for expansion. However, in 1908 Austria-Hungary had frustrated Serbian ambitions by calmly annexing the states of Bosnia and Herzegovina, immediately to the north of Serbia. In 1912 and 1913 there were two minor wars in the Balkans, the outcome of which was that Turkey was almost driven out of Europe but acquired a new friend in Germany and began receiving German arms and German officers. Russia viewed with satisfaction the fact that its potential allies had increased their influence, while Austria-Hungary was now seriously alarmed by the progress of aggressive small powers, such as Serbia, which could help further to undermine the ramshackle Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Next page