Field Marshal Earl Haig by Philip Warner

Index of Contents

Acknowledgements

Introduction: The Haig Enigma

Chapter 1 Early Life

Chapter 2 From Sandhurst to Staff College

Chapter 3 Haig on Active Service

Chapter 4 In Pursuit of the Boers

Chapter 5 A Changing Scene

Chapter 6 Domestic Interlude

Chapter 7 The Clouds Gather

Chapter 8 The World at War

Chapter 9 The Road to Ypres

Chapter 10 Attrition

Chapter 11 Commander-in-Chief

Chapter 12 The Battle of the Somme

Chapter 13 Enemies on All Sides

Chapter 14 Unexpected Hazards

Chapter 15 Public Service

Chapter 16 Some Judgements

Chapter 17 The Jury Is Out

Select Bibliography

Picture Gallery

Philip Warner A Short Biography

Philip Warner A Concise Bibliography

Acknowledgements

I am deeply grateful to many people for their generous assistance to me while I was writing this book.

Earl Haig, the son of the Field Marshal, has directed my attention to many sources from which I received valuable information, and in addition lent me books, photographs and documents from his own collection. Lady Dacre of Glanton, the Field Marshals daughter, provided valuable insight into her fathers character and career. Lord Blake very kindly gave me permission to quote from his book The Private Diaries of Sir Douglas Haig 191418 . Lord Windlesham, Principal of Brasenose College, Oxford, provided me with material from the College archives, and drew my attention to essential points. General Sir Michael Gow very kindly sent me copies of Haigs speeches.

The curator and staff of the National Library of Scotland gave me every possible assistance in my study of the Haig archives in their care. Mr Derek Winterbottom, Head of History and Archivist at Clifton College, sent me valuable Haig material, showed me round the school and provided the answers to many questions which had previously baffled me.

Mr Roderick Suddaby, Keeper of the Documents at the Imperial War Museum, gave me his customary guidance, help and advice, all of which were invaluable. Mr Andrew Orgil, Librarian at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, and his patient staff gave me unlimited help in tracing sources of information. Mr John Terraine generously gave me help and guidance on Haig, of whom his knowledge is unlikely to be equalled, let alone surpassed. Mr Leo Cooper was, once more, a source of essential advice, guidance and encouragement. Dr John Sweetman, Head of Defence and International Affairs at the RMA Sandhurst, assisted me greatly in free-ranging discussions of military policy in the First World War. Mr John Hussey very kindly lent me his carefully and fully researched paper on Haigs loan to Sir John French.

These are but a few of the many people who, over the years, have helped in the preparation of the book, and though there is not space to list them all, this does not mean that my debt to them is any the less.

Introduction: The Haig Enigma

Douglas Haig is probably the most controversial figure in British military history, perhaps in all military history. It fell to Haig to command the largest army Britain had ever put into the field, a total of over two million men. No previous military commander had ever held such a powerful position. Before Haig, the fate of nations had been settled by battles between a few thousand men; to control armies of one hundred thousand or more had been considered impossible for any single man although, of course, armies had occasionally reached and exceeded that figure. During the Second World War vast numbers were again put into the field, but by that time there had been a revolution in communications and the Commander-in-Chief could be better aware of what was happening in the front line than if he had actually been in it himself. Between 1914 and 1918, however, such communications were unimaginable. Winston Churchill said of Haig: He might be, he surely was, unequal to the prodigious scale of events; but no one else was discerned as his equal or his better.

This book is therefore neither a eulogy nor a condemnation of Haig. It is an attempt to assess his task objectively and to decide whether he was better or worse at it than he might have been. His life story is interesting because it shows how he evolved from Haig the apparently undistinguished, industrious junior officer into the man who presided over the army which won the most gruelling war in history. If the criterion of a successful general is to win wars, Haig must be judged a success. The cost of victory was appalling, but it needs to be remembered that Haigs military operations were in accordance with the ideas of the time, when attrition was the method by which all the belligerents hoped and planned to achieve the desired result. The Germans fought a war of attrition, and so did the French until the casualties of the 1916 and 1917 battles became more than they could sustain. The Russians, too, planned a war of attrition: unfortunately for them, their military organisation was so incompetent than their armies collapsed at the front and their munitions and supply systems failed behind the lines. These are matters which will be examined in greater detail later.

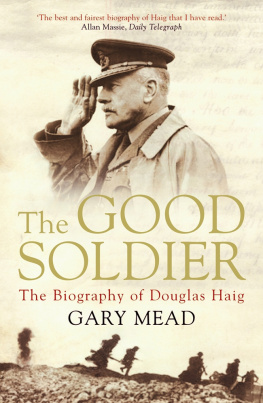

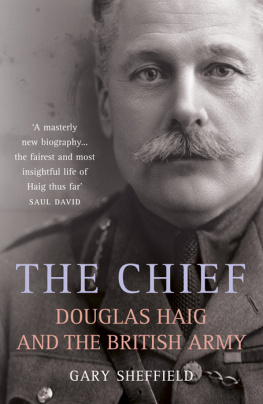

Inevitably a number of books have been written about Haig, but nevertheless they are fewer than might have been expected. The writers have varied considerably in their opinions and their approaches. A number of them have denounced him as Butcher Haig, finding ample proof for their views in the horrific casualty figures of the Western Front figures only too clearly supported by the rows of headstones in the cemeteries of northern France. Some explain these casualties as being due to Haigs obstinacy and incompetence; some see a darker side and attribute them to a selfish indifference to the size of the sacrifice. Other writers, often military ones, have decided that Haig was incompetent because he had been promoted far beyond the rank he should properly have held. This ingenious argument makes Haig a victim of circumstances. Yet others have taken the opposite view, finding many examples of Haigs efficiency and suitability for his exacting role. And there are military writers who take an almost romantic view, seeing Haig as a man who did astonishingly well when faced with a virtually impossible task.

There have been good books on Haig and bad books on Haig. There have been books by writers who knew about soldiering but not about writing biographies, and there have been their opposites who knew something, but not a lot, about biographies, but had nothing in the way of balanced military knowledge. Some inaccuracies about his life have been repeated in volume after volume, obviously accepted uncritically.

Time does not blur the stark realities of the First World War the Great War, as it was known until the Second came along. No one who walks among the graves in northern France, on the Somme, at Passchendaele or at Loos, to mention only a few locations, can clear his or her mind of emotion. Nor should they. The German cemeteries are equally moving. Among the vast losses and sufferings certain reminders still evoke almost unbearable anguish. War memorials which record the loss of all the sons in one family, or occasions when entire districts lost their young men in battalions such as the Bradford Pals, the Leeds Pals or the Manchester Pals, have a special poignancy. Even the replica trenches which are now beginning to appear in museums in Britain and France convey something which is so far removed from ordinary experience that the visitor can scarcely comprehend it.

The full realisation that the war was horrific for both sides came when Erich Maria Remarque published his chilling account All Quiet on the Western Front in 1929. There was a concept of mutual suffering in many other books about the war, although it was often implied rather than stated. Robert Gravess Goodbye to All That , Edmund Blundens Undertones of War , Cecil Robertss Spears Against Us , and the poems of Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen and Isaac Rosenberg convey something of it.

Next page