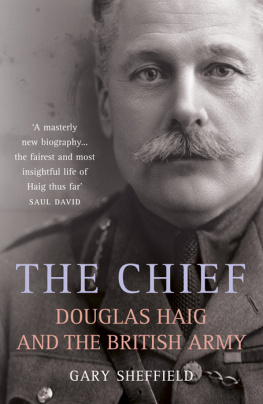

THE GOOD SOLDIER

Gary Mead was a journalist with the Financial Times for

ten years. He is the author of The Doughboys: America

and The First World War (2000).

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Atlantic Books,

an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

This edition published in Great Britain in 2014

by Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright Gary Mead, 2007

The moral right of Gary Mead to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission both of the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make goodany omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the

earliest opportunity.

ISBN 9781843542810

eISBN 9781782394969

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

Atlantic Books Ltd.

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to the memory of Charles Hemming teacher and friend, and the finest example of the impossibility of ever really knowing anyone.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is one of the pleasures of writing a book that one is frequently reminded of the innate kindness of strangers, who respond with generosity and warmth to a query for help that arrives out of the blue. Another is the process of discovery and acquiring greater understanding, and through that having ones prejudices demolished. I owe considerable debts to a number of people who have been very supportive of my writing this book. At Atlantic Books, Toby Mundy, publisher, has been very patient and encouraging; Angus MacKinnon, who commissioned the book, has been a tower of calm strength and has been unflagging in his intellectual engagement in the project no author could wish for a better editor; Emma Grove has taken a keen interest and helped in numerous ways to steer it into print. Barry Holmes and Polly Lis gave unparalleled professional service in the editing process. My literary agent, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, has shown his usual unswerving confidence and extended unfailingly kind and regular morale-boosting. Colm McLaughlin, curator of the Haig Archive, and other staff at the National Library of Scotland (hereafter NLS), pointed me in fruitful and previously unexplored directions. Writers on the First World War and Douglas Haig owe a large debt to the 2nd Earl Haig for enabling access to the Haig archive at the NLS; I additionally owe a personal one for his agreeing to meet me and talk about his father, Field Marshal Earl Haig. Professor Hew Strachan of All Souls College, Oxford University, whose grasp of the events and personalities of the First World War is unrivalled, read the manuscript and placed some episodes in a wider, more complex context than I had previously considered, as well as ensuring that some mistakes were suffocated before print. Those that may inadvertently remain are entirely my responsibility.

Denise Brace at the Museum of Edinburgh was inordinately helpful in photographic research, as were Dr A. R. Morton at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst and David Fletcher, historian at the Tank Museum, Bovington, and archivists at the Imperial War Museum in London. Michael Orr provided much useful material from the records of the Douglas Haig Fellowship. Andrew Jefford gave me new insights into the Scottish whisky business. Matthew Turner helped me understand more of the difficulties of trying to measure the relative value of money over time. Martin Hornby of the Western Front Association provided me with useful background research materials. Colonel John Wilson, editor of the British Army Review, generously provided me with archive resources. Elizabeth Boardman, Archivist at Brasenose College, Oxford University, yielded fresh insights into the shifting perceptions of Haig.

The London Library is a remarkable entity, having under one roof so many of the essential materials that would otherwise be almost impossible to consult. The literature on Douglas Haig, the British army he spent his life serving, and the First World War is staggeringly vast and daily added to; a book of this kind could not exist without the work of many previous scholars and writers. The bibliography should be understood not as claiming a spurious authority but rather as a gesture of appreciation to some of those who have toiled before. Last but far from least, it would have been impossible to get this far without the support of my wife Jane and our daughters Freya, Theodora, and Odette, who bore this lengthy enterprise with fortitude, fun and frankness they stoically endured a lot of absent fatherhood.

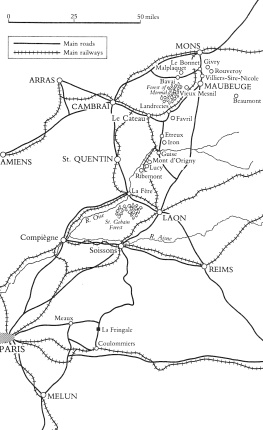

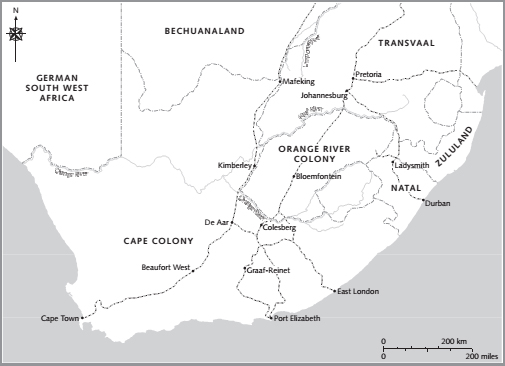

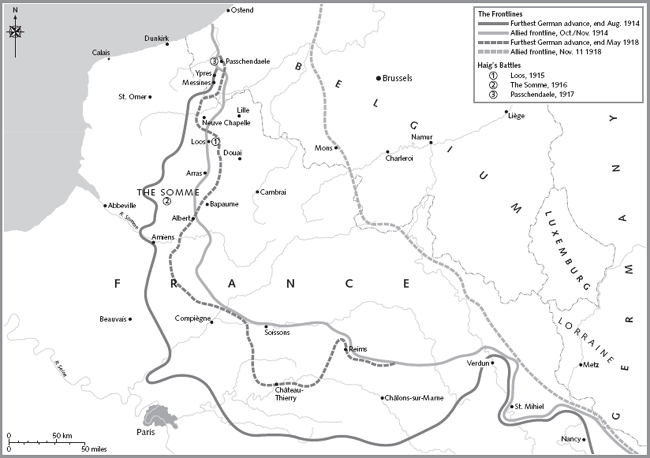

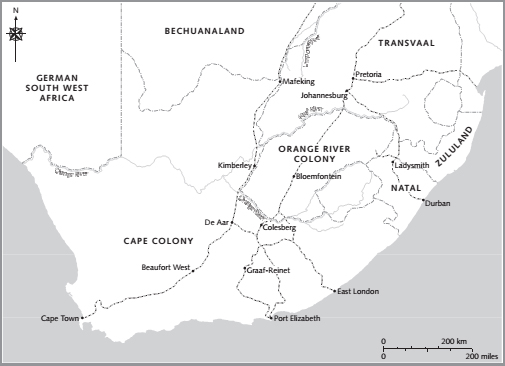

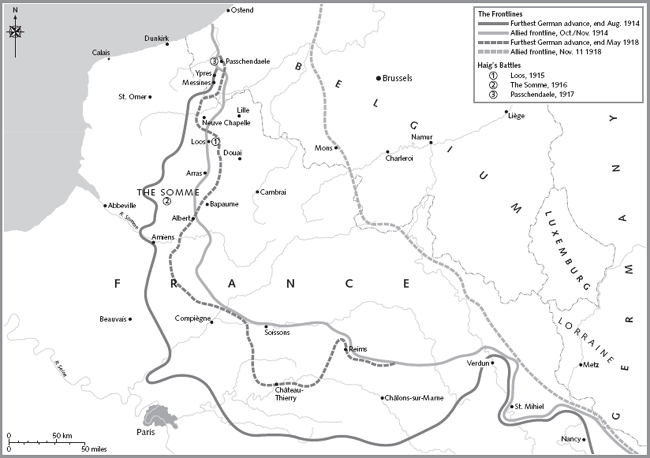

LIST OF MAPS

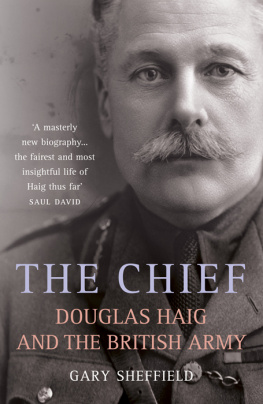

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Section 1

Section 2

Section 3

INTRODUCTION

Neither Butcher nor Saint

There is little doubt that Haig was an idiot.

The unofficial Australian view; see www.diggerhistory.info

Arguably he killed as many of his own men as Stalin and Hitler put together.

Andrew Grimes, Manchester Evening News, November 1998

As any historian who has tried even mildly to be revisionist about Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig on television will acknowledge, there is a corpus of opinion which is not overly interested in the facts because it has already made up its mind.

Richard Holmes, foreword to Blindfold and Alone, Cathryn Corns & John Hughes-Wilson, Cassell, 2001

Douglas Haigs misfortune as a British general is that he was born and schooled in one era but had to fight his most important battles in another. His Victorian upbringing could not prepare Haig, nor anyone, for the stalemate of the Western Fronts trenches and the incremental technological improvements which gradually made possible the grudging victory of November 1918. Haig was a cavalryman by profession and faith, who never felt comfortable using the telephone and never travelled in an aeroplane. His experiences in Sudan and South Africa had more in common with that of the Duke of Wellington who died less than a decade before Haigs birth than the battlefields of 191418, which saw the tank supersede the horse in attack, radio communications displace the telegraph, and aircraft come into their own as the eyes of command. Haigs inexorable rise to the highest reaches of the British army coincided with a remarkable social, political and technological change in human affairs. This wider social revolution affected all aspects of life, including the military. Perhaps the greatest advantage officers of Haigs era had over those in Wellingtons time was simply that, unlike their predecessors, they had access to a professional education. The training available at the Royal Military College at Sandhurst (established in 1800) and the Staff College at Camberley (revived in 1857) was perhaps not ideal, but at least it was a schooling of sorts in their chosen profession; that in itself draws Haig closer to Montgomerys era rather than Welling tons. Although the popular view of Haig is that he was little more than a snobbish and ignorant opponent of all such change, this innately conservative man proved himself remarkably flexible in using and getting others to use new technology, once he was convinced it offered greater chance of success on the battlefield.