THE SOLDIER'S WAR

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Tickled to Death to Go

Veterans: The Last Survivors of the Great War

Prisoners of the Kaiser

The Trench

Last Man Standing

All Quiet on the Home Front

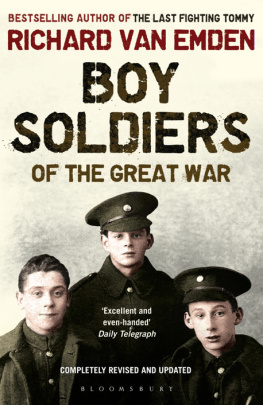

Boy Soldiers of the Great War

Britain's Last Tommies

The Last Fighting Tommy

(with Harry Patch)

Famous

THE SOLDIER'S WAR

The Great War Through Veterans' Eyes

Richard van Emden

Dedicated to my wife Anna and to our wonderful son Benjamin

First published in Great Britain 2008

Copyright Richard van Emden 2008

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material

reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked

the publishers would be glad to hear from them. For legal purposes

the acknowledgements on page 378

constitute an extension of the copyright page

The moral right of the author has been asserted

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any

manner whatsoever without written permission from the Publisher except

in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

36 Soho Square

London W1D 3QY

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury Publishing, London, New York and Berlin

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 07475 97803

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

The paper this book is printed on is certified by the 1996 Forest Stewardship

Council A.C. (FSC). It is ancient-forest friendly. The printer holds

FSC chain of custody SGS-COC-2061

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

The following abbreviations are used throughout the text:

Ranks | Units |

Brigadier Brig. | Battalion Bttn |

Captain Capt. | Battery Batt. |

Company Sergeant Major CSM | Company Coy |

Corporal Cpl | Division Div. |

Gunner Gnr | Machine Gun Corps MGC |

Lance Corporal L/Cpl | Regiment Rgt |

Lieutenant Lt | Royal Army Medical Corps RAMC |

Lieutenant Colonel Lt Col |

Major Maj. | Royal Engineers RE |

Private Pte | Royal Field Artillery RFA |

Quarter Master Sergeant QMS | Royal Garrison Artillery RGA |

Reverend Rev. | Royal Horse Artillery RHA |

Second Lieutenant 2/Lt | Yeomanry Yeo. |

Sergeant Sgt |

Sergeant Major Sgt Maj. |

Trooper Trp. |

INTRODUCTION

During the later stages of the Battle of the Somme, Major A. G. P. Hardwick surveyed the morass in front of him. He was standing outside a large dugout which, he was informed, had previously been an enemy bakery. It was situated in a communication trench leading to the front line, a captured German trench. 'The dugout is a huge place,' he recalled, 'and many direct hits have made no effect on it. Its entrances are three, leading in from the trench, and it is below ground level about twenty-five feet.' He admired the technical skill required in its construction, lined as it was with twelve-inch-square timber, both roof and walls; the floor, too, was made of wood. Until they were relieved, it was the temporary home for the 76th Field Ambulance, and in the preceding days Hardwick and his comrades had brought many a casualty in for treatment. The issue had never been the quality of the accommodation, but rather, how, once they had left the dugout and the trench, they might find it again in a largely featureless terrain, blasted into utter submission by shellfire.

'Our landmarks to this place are very few and a compass is going to be indispensable here our chief marks are in order. (1) Trench- board over a wide trench, (2) Then made due N for a smashed up harrow, (3) A smashed Boche limber cart in a shell hole, (4) Then two dead Huns lying in a shell hole.'

His description reflects the common perception of the Western Front, a place of desolation and destruction, but it is a vision that ignores and excludes all other reality.

Some eighteen months earlier, in 1915, Denis Barnett, a young lieutenant in the 2nd Leinster Regiment, was faced with a similar problem to Hardwick's. In his case, he was leading a working party forward to undertake a job near the firing line at Ypres. In the dark, he had only a few pointers to guide his way, but he had carefully noted them so as to avoid going astray: 'It is a very difficult journey from here to where we are digging, and the "sailing" directions are like this: "across field to haystack; bear half left to dead pig; cross stream 25 yards below dead horse; up hedge to shell hole, and then follow the smell of three dead cows across a field, and you'll arrive at exactly the right place"!'

Both Hardwick and Barnett had, it appeared, an equal chance of getting lost, but there was one stark difference: the terrain in which they were working. The once picturesque Somme had, by November 1916, taken on the mantle of the best moonscape ever fashioned by man. On the other hand, in 1915 the Ypres Salient still maintained its distinctive agricultural feel.

Nearly twenty years ago, I was fortunate enough to travel back to France and Belgium with a friend, Benjamin Clouting, a former trooper in the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards. He had served on the Western Front for the duration of the war, and was wounded twice. As we travelled away from the Belgian town of Ypres into the infamous Salient beyond, we stopped to look at the ground where he was wounded in May 1915. Ben peered from the coach window towards the railway cutting where, seventy-five years earlier, he had taken shelter from German shellfire. I remember looking in the same direction. I saw the cutting and in my mind's eye I pictured Ben sitting there, shrapnel in his ankle, surrounded by a marshland, a place of lip-to-lip shell holes and uninterrupted mud. I was not, as I realise now, picturing 1915, but 1917, the world of the Battle of Passchendaele a landscape I had been educated to expect, from school lessons and Great War poetry. The history of that war was not taught in the context of 1915 but firmly that of 1916 and 1917. Understandably, the 191418 war was pictured as horrific, endlessly brutal and at times beyond human endurance. It would have been hard to inspire such a vision had the teacher mentioned the luscious fields of wild flowers a bee's paradise or the grass growing wild in uncultivated fields, to be nightly scythed by soldiers. It would not have helped if he had told of agricultural implements lying redundant near unkempt haystacks, of partially intact farm buildings, or intrepid farmers who still sought to harvest a least a little of their crop within sight of the trenches.

The annals of any war, it is said, are told in the history of its great battles, its decisive turning points, primarily military but also political. The rights and wrongs of decisions to launch offensives are still hotly debated, the tactical success or failure of new instruments of war are reviewed and reviewed again. Those key moments in an offensive which were exploited or missed are still argued over, and ideas are developed as to what might have been. And then the history of the battles themselves is told from the point of view of the High Command, and then told again through the voices of those who took part in the fighting at Mons, Gallipoli, Loos, the Somme, Arras, Ypres, Cambrai et al.: they have all had books written about them.

Next page