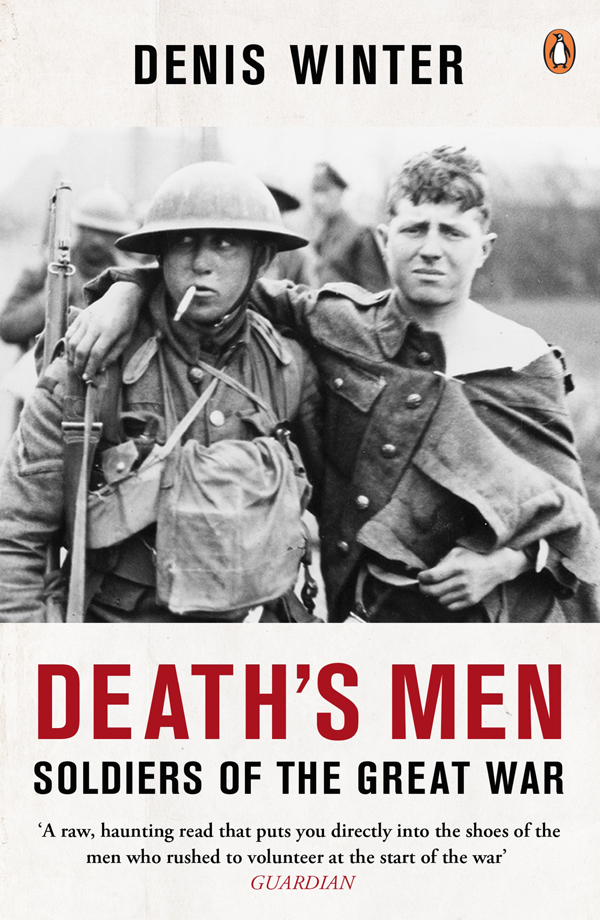

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Allen Lane 1978

Published in Penguin Books 1979

Reissued in this edition 2014

Copyright Denis Winter, 1978

Cover image Mary Evans /Robert Hunt Collection

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-96921-2

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

List of Illustrations

The author and publishers are grateful to the Imperial War Museum for permission to use the photographs.

Acknowledgements

No book on war can be written without accumulating many debts. My deepest gratitude is to those hundreds of writers, dead for the most part, whose works are the basis of the book. I was often moved by their memories, while the vigour and immediacy of the battle scenes disturbed my sleep over several years. This book, however unworthy, is their memorial. Most of my published material was digested, a suitcase a week, from the basement shelves of West Hill Library, Putney. Without the free run of their shelves the book could not have been written. I am also grateful to the following for permission to quote material: Anthony Shiel Associates for extracts from P. Maze, A Frenchman in Khaki; Newnes-Butterworths for extracts from E. Swinton, Twenty Years After. The Lament of the Demobilized by Vera Brittain is included with the permission of Sir George Catlin and her literary executors. The majority of the unpublished material used was from the Imperial War Museum. Mr Suddaby and his staff made their resources freely available to an irritable inquirer with odd working habits. Valuable material came from the libraries of Eton College and Cambridge University. The courtesy and helpfulness of both libraries went even beyond what I came to expect from library staff. It is a pleasure to record the assistance received from staff at Watford Central Library, Paddington Library and the photographic collection at the Imperial War Museum. For permission to spend a day talking to the veterans of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea, my thanks to the authorities. A particular debt is owed to Clive Trebilcock at Pembroke College, Cambridge; H. Strachan, research fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge; David Duguid of Penguin Books and my father. All went through the manuscript at various stages and saved it from the crassest errors of fact and judgement. Those which remain are due to my own failings. My thanks finally to Miss Eleo Gordon, adjutant to the project in its final stages.

The smallest detail taken from an actual incident in war is more instructive to me, a soldier, than all the Thiers and Jominis in the world. They speak for the heads of states and armies, but they never show me what I wish to know a battalion, company or platoon in action. The man is the first weapon of battle. Let us study the soldier for it is he who brings reality to it.

(Aron Du Picq, pioneer writer on the behaviour of men in war and

Crimean war veteran who died in battle in the FrancoPrussian war)

Introduction

In the Great War more than five million Britons wore military uniform and were involved, in various capacities, in the war effort, for varying periods. But, both during and after the war, the individual voices of the soldiers were lost in the collective picture. Men drew arrows on maps and talked of battles and campaigns, but what it felt like to be in the front line or in a base hospital they did not know. Civilians did not ask and soldiers did not write. Just as in the Napoleonic wars or in our own time, Vietnam or Northern Ireland, the experiences and inner lives of the other ranks were as private and unknown as those of Kalahari bushmen.

Just ten years after the end of the Great War it seemed that there might be a change. For five years, a number of memoirs were published, of which the works of Graves and Sassoon are the most widely read today. Then the public grew weary and moved on to think about unemployment or the dictators growing power. The war could surely not have been so black? There must have been invention and exaggeration. From Oxford Cyril Falls, the professor of war studies, warned civilians against even the most reputable of war memoirs. He pointed out that a popular war writer like Montague was over-sensitive and that Robert Graves, being an intellectual, had a mind less penetrating than that of the common man. Civilians came to agree with him in the thirties.

After thirty years of virtual silence, the fiftieth anniversaries brought renewed interest. This may have been due to the Great War series on television or perhaps to the need to find a moment in time when the fatal haemorrhage and the decline from power began. Again the books began to flow. Compared with the thirties, there was one big change: the memoirs of generals and fighting soldiers were replaced by descriptions of battles and whole campaigns. Their bibliographies were generally brief and made up of the Official History of the war plus regimental and divisional histories. This may well have been a matter of abbreviating research. Equally, it may have reflected that distrust of le menu peuple so common among British historians. One of our best military writers, Hubert Essame, remarked that poets are temperamentally unsuited for any form of service in the infantry; while soldier writers are exceptional and rare anyway; the majority of serving soldiers saw the war differently and so on. What emerges are works which enlarge our understanding of strategy, re-create battles chronologically using the wide brush of unit movements and throw in vivid, action-packed vignettes to speed the pace of the battle accounts. The soldiers war is at best relegated to a single chapter with colourful accounts of mud and vermin, bully beef and particular deaths in battle.