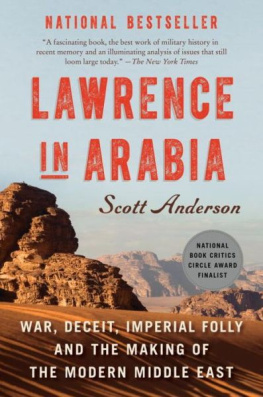

Copyright 2013 Scott Anderson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

A Penguin Random House Company

www.doubleday.com

DOUBLEDAY and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Frontispiece photograph copyright Imperial War Museum (Q58838)

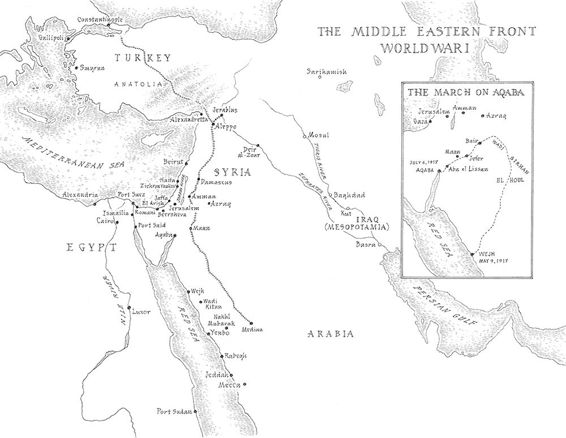

Endpaper maps designed by John T. Burgoyne

Front jacket photograph by Taylor S. Kennedy/ National Geographic Stock

Jacket design by John Fontana

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Anderson, Scott.

Lawrence in Arabia : war, deceit, imperial folly and the making of the modern Middle East / Scott Anderson. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Lawrence, T. E. (Thomas Edward), 18881935.

2. World War, 19141918CampaignsMiddle East.

3. World War, 19141918CampaignsTurkey.

4. Middle EastHistory19141923. 5. SoldiersGreat BritainBiography.

6. Great Britain. ArmyBiography. I. Title.

D568.4.L45 A66 2013

940.41241092dc23

[B] 2012049719

eBook ISBN: 978-0-385-53293-8

Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-385-53292-1

v3.1_r1

To the two loves of my life,

Nanette and Natasha

Contents

Authors Note

In war, language itself often becomes a weapon, and that was certainly true in the Middle Eastern theater of World War I. For example, while the Allied powers tended to use the Ottoman Empire and Turkey interchangeably, they displayed a marked preference for the latter designation as the war went on, undoubtedly to help fortify the notion that the non-Turkish populations of the Ottoman Empire were somehow captive peoples in need of liberation. Similarly, while early-war Allied documents often noted that Palestine and Lebanon were provinces of Ottoman Syria, that distinction tended to disappear as the British and French made plans to seize those territories in the postwar era. On a more subtle level, all the Western powers, including the Ottoman Empires/Turkeys chief ally in the war, Germany, continued to refer to the city of Constantinople (its name under a Christian empire overthrown by the Muslim Ottomans in 1453) rather than the locally preferred Istanbul.

As many Middle East historians rightly point out, the use of these Western-preferred labelsTurkey rather than the Ottoman Empire, Constantinople instead of Istanbulis indicative of a Eurocentric perspective that, in its most pernicious form, serves to validate the European (read imperialist) view of history.

This poses a dilemma for historians focusing on the Western role in that war theateras I do in this booksince the bulk of their research will naturally be drawn from Western sources. In such a situation, it would seem a writer must choose between clarity and political sensitivity; since I feel many readers would find it confusing if, for example, I consistently referred to Istanbul when virtually all cited material refers to Constantinople, I have opted for clarity.

I was aided in this decision, however, by the fact that these language distinctions were not nearly so clear-cut at the time as some contemporary Middle East historians contend. Even the wartime leadership of the Ottoman Empire/Turkey frequently referred to the city of Constantinople, and also tended to use Ottoman and Turkey synonymously (see the epigraph from Djemal Pasha in Chapter One). To dwell on all this too long is only to invite more complications. As Ottoman historian Mustafa Aksakal readily concedes in The Ottoman Road to War (pp. xxi), it seems anachronistic to speak of an Ottoman government and an Ottoman cabinet in 1914 when the major players had explicitly repudiated Ottomanism and were set on constructing a government by and for the Turks...

In sum, like the principals in this book, Ive used Ottoman Empire and Turkey somewhat interchangeably, guided mostly by what sounds right in a particular context, while for simplicity, I refer exclusively to Constantinople.

On a different language-related matter, Arabic names can be transliterated in a wide variety of ways. For purposes of consistency, I have adopted the spellings that appear most often in quoted material, and have standardized those spellings within quoted material. In most cases, this adheres to Egyptian Arabic pronunciation. For example, a man named Mohammed al-Faroki, whose surname appeared in different documents of the time also as Faruqi, Farogi, Farookee, Faroukhi, etc., will appear as Faroki throughout. The most notable case in point is that of T. E. Lawrences chief Arab ally, Faisal ibn Hussein, usually referred to as Feisal by Lawrence, but as Faisal by most others, including historians. To avoid confusion, Ive changed all spellings to the latter.

Also, the use of English punctuation has changed quite dramatically over the past century, and Lawrence in particular had an extremely idiosyncraticsome might say antagonisticapproach to it in his writing. In quotations where I believed the original punctuation might obscure meaning for modern readers, I have adopted the modern norm. These changes apply only to punctuation; no words have been added or deleted from quotations except where indicated by brackets or ellipses.

Finally, two versions of Seven Pillars of Wisdom were published in T. E. Lawrences lifetime. The first, a handprinted edition of only eight copies, was produced in 1922 and is commonly referred to as the Oxford Text, while a revised edition of approximately two hundred copies was produced in 1926; it is this latter version that is most commonly read today. Since Lawrence made clear that he regarded the Oxford Text as a rough draft, I have quoted almost exclusively from the 1926 version. In those few instances where Ive quoted from the Oxford Text, the endnote citation is marked (Oxford).

Introduction

O n the morning of October 30, 1918, Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence received a summons to Buckingham Palace. The king had requested his presence.

The collective mood in London that day was euphoric. For the past four years and three months, Great Britain and much of the rest of the world had been consumed by the bloodiest conflict in recorded history, one that had claimed the lives of some sixteen million people across three continents. Now, with a speed that scarcely could have been imagined mere weeks earlier, it was all coming to an end. On that same day, one of Great Britains three principal foes, the Ottoman Empire, was accepting peace terms, and the remaining two, Germany and Austria-Hungary, would shortly follow suit. Colonel Lawrences contribution to that war effort had been in its Middle Eastern theater, and he too was caught quite off guard by its rapid close. At the beginning of that month, he had still been in the field assisting in the capture of Damascus, an event that heralded the collapse of the Ottoman army. Back in England for less than a week, he was already consulting with those senior British statesmen and generals tasked with mapping out the postwar borders of the Middle East, a once-fanciful endeavor that had now become quite urgent. Lawrence was apparently under the impression that his audience with King George V that morning was to discuss those ongoing deliberations.