This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781407091310

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Vintage 2008

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

Seven Pillars of Wisdom was privately printed in 1926

This text follows the edition which was first published for general circulation by Jonathan Cape in 1935

Vintage

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA

www.vintage-classics.info

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099511786

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at: www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Bookmarque, Croydon CR0 4TD

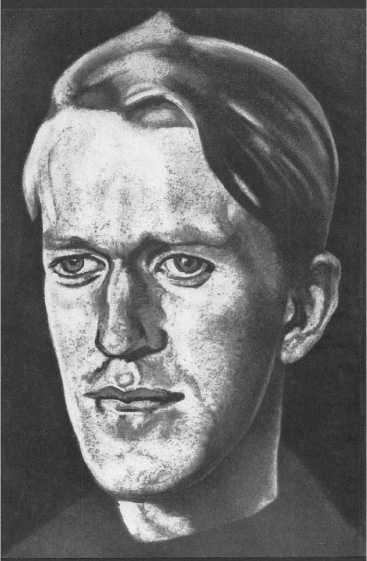

About the Author

Thomas Edward Lawrence was born on 16 August 1888 in Tremadoc in Wales. He attended Jesus College, Oxford where he became interested in the Middle East. He studied Arabic and between 1910 and 1914 worked for the British Museum on an archaeological excavation of Carchemish on the Euphrates. During the First World War he worked for the British Intelligence Service and his activities while fighting alongside the Arab forces earned him the nickname Lawrence of Arabia. After the war he worked as an adviser to the Colonial Office until his resignation in 1922. He enlisted in the RAF the same year under a pseudonym in order to escape his celebrity. He later changed his name by deed poll to T.E. Shaw. The first manuscript of Seven Pillars of Wisdom was lost at Reading train station in 1919 and Lawrence was forced to rewrite it from memory. It was initially published in a private edition in 1926 and only became widely available in 1935. An abridged version, Revolt in the Desert was published in 1927. Lawrence died in a motorcycle accident near his home in Dorset on 19 May 1935. His final book, The Mint, was published posthumously.

OTHER WORKS BY T.E. LAWRENCE

Revolt in the Desert

The Odyssey of Homer

Crusader Castles

The Mint

Introduction

No wonder Seven Pillars of Wisdom indeed, all of T. E. Lawrences work now tops the reading list of almost every senior US officer in Iraq. Long after his legend was established in Arabia and Damascus and at the Versailles Treaty negotiations almost 90 years after he realised that his promises to his Arab allies were to be broken by Britains adherence to the Balfour declaration Lawrences wisdom is now serving to guide (and no doubt misguide) the Americans who have walked into the hell-disaster of Iraq with no idea of how to retreat. If only, I say to myself each time I arrive in Baghdad, the Americans had read Lawrence before they invaded.

Its not just Lawrences experience of betrayal that is of importance. His promise of independence to the Arabs who had promised to fight the Ottoman Turks as allies of Britain proved as false as the US pledges to bring freedom, security and democracy to Iraqis. If recent research has revealed that Lawrence was partial to Zionism, he never failed to reflect on the treachery which he had unwittingly committed against the Arabs. Britains support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine was a promise made at the height of the 191418 war, when Britain was desperate for Jewish support. And Lawrences promise of freedom to the Arabs was made when the United Kingdom was desperate for Arab support against the Turks. And promises are meant to be kept. Lawrences, of course, were not.

There is something painfully self-absorbed about Lawrence of Arabia. His obsessive wearing of Arab gowns his preparedness to be photographed as an Arab and his constant identification of himself with Arabs, suggest a man whose politics had taken on a distinctly personal, almost theatrical role. Even at Versailles and we have only to look at the photograph of him as he stands next to the Arab delegation in Paris he chose to wear an Arab kuffiah headdress. Seven Pillars of Wisdom is an epic of literature but it is also the story of a deeply distressed man whose depression eventually turned him into a cynical figure who tried to hide his identity (not very successfully, it is true) among the humble aircraftmen of the RAF.

Yet his wisdom did not desert him after the 191418 war. When insurgents staged a rebellion against the post-war British occupation of Iraq in 1920, Lawrence dispensed advice in the pages of London newspapers which the Americans and the departing British should have read before they staged their illegal invasion of the same country in March of 2003. Although on a far smaller scale, the 1920 insurgency was an almost fingerprint-perfect forerunner of the present Iraqi conflict. British troops who were assured they would be greeted as liberators found that their supposed beneficiaries were far from happy to see them; Arab-Ottoman soldiers who waited to join the Allied side were abused in prison camps. When the first British officer was killed outside Baghdad, the British army besieged with field guns the Sunni city of Fallujah and later surrounded the Shia city of Najaf, demanding the surrender of a militant Shia cleric. British intelligence in Baghdad informed the war department in London that insurgents were crossing the border into Iraq from Syria. And Lloyd George, the British prime minister, assured the House of Commons at a time when the British were tired of sacrificing their soldiers in Mesopotamia that if UK and Empire forces were to withdraw from Iraq, there would be civil war.

Lawrence had much to say about this now familiar

As a result, the British turned to air power to suppress the insurgents. Lawrence wrote a letter to the Observer, describing how these risings take a regular course. There is a preliminary Arab success, then British reinforcements go out as a punitive force. They fight their way (our losses are slight, the Arab losses heavy) to their objective, which is meanwhile bombarded by artillery, aeroplanes or gunboats. But Lawrence had an irritating cynicism bordering on black humour its initial appearance can be faintly observed in Seven Pillars which could make him appear not just unattractive but positively sadistic. It is odd that we do not use poison gas on these occasions, he wrote in the same letter. Bombing the houses is a patchy way of getting the women and children, and our infantry always incur losses in shooting down the Arab men. By gas attacks the whole population of offending districts could be wiped out neatly.