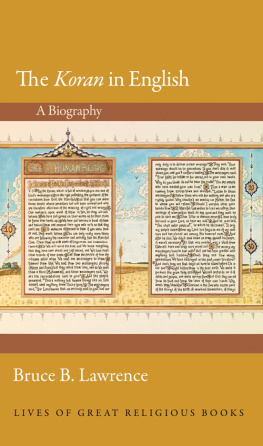

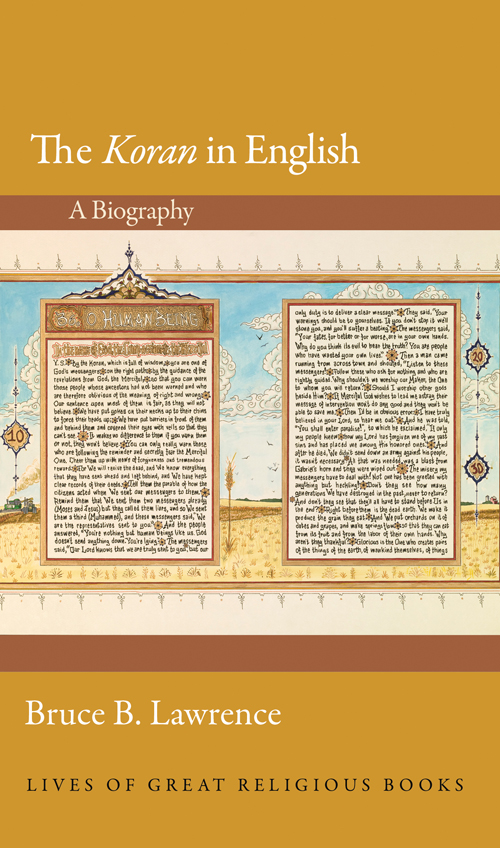

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Koran in English

LIVES OF GREAT RELIGIOUS BOOKS

The Dead Sea Scrolls, John J. Collins

The Bhagavad Gita, Richard H. Davis

John Calvins Institutes of the Christian Religion, Bruce Gordon

The Book of Mormon, Paul C. Gutjahr

The Book of Genesis, Ronald Hendel

The Book of Common Prayer, Alan Jacobs

The Book of Job, Mark Larrimore

The Koran in English, Bruce B. Lawrence

The Lotus Stra, Donald S. Lopez Jr.

The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Donald S. Lopez Jr.

C. S. Lewiss Mere Christianity, George M. Marsden

Dietrich Bonhoeffers Letters and Papers from Prison, Martin E. Marty

Thomas Aquinass Summa theologiae, Bernard McGinn

The I Ching, Richard J. Smith

The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, David Gordon White

Augustines Confessions, Garry Wills

FORTHCOMING

The Book of Exodus, Joel Baden

The Book of Revelation, Timothy Beal

Confuciuss Analects, Annping Chin and Jonathan D. Spence

The Autobiography of Saint Teresa of Avila, Carlos Eire

Josephuss The Jewish War, Martin Goodman

Dantes Divine Comedy, Joseph Luzzi

The Greatest Translations of All Time: The Septuagint and the Vulgate,

Jack Miles

The Passover Haggadah, Vanessa Ochs

The Song of Songs, Ilana Pardes

The Daode Jing, James Robson

Rumis Masnavi, Omid Safi

The Talmud, Barry Wimpfheimer

The Koran in English

A BIOGRAPHY

Bruce B. Lawrence

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton,

New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

Jacket art: Initial panel from American Quran (Sandow Birk). Courtesy

of the Catherine Clark Gallery of San Francisco and Sandow Birk

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lawrence, Bruce B., author.

Title: The Koran in English : a biography / Bruce B. Lawrence.

Description: Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press, [2017] |

Series: Lives of great religious books | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016045969

ISBN 9780691155586 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: QuranTranslations into EnglishHistory and

criticism.

Classification: LCC BP131.15.E54 L39 2017 | DDC 297.1/225dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016045969

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Garamond Premier Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To James Kritzeck (19301986)

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

PREFACE

To translate or not to translate? When the text in question is the Arabic Quran there has always been hesitation, reluctance, and even resistance to translate. In English Quran became Anglicized as Koran, and since the eighteenth century Koran has supplanted all other options as the most frequently used substitute for Quran in Euro-American circles. Yet the Koran did not, and for some it cannot, replace the Quran; only the latter, the Arabic Quran, is deemed to be the Word of God, the Noble Book, disclosed in the seventh century of the Common Era. At once holy and ancient, it was said to be revealed directly from the divine source, Allah, via a celestial intermediary, the Archangel Gabriel, to a human receptor, the Arab prophet Muhammad. Of itself, it says:

A Book whose signs have been distinguished

as an Arabic Koran for a people having knowledge.

Q 41:3

Or sometimes it simply refers to itself as the Koran, as in:

Y. S. By the Koran, which is full of wisdom

Q 36:12

The truth of Islam as a revealed religion rests on a double axis. It is predicated both on prophecy as a divinely initiated process and its finality in the person of Muhammad: he was the last prophet who received the last revelation as signs (with Arabic, ayat, also meaning verses) in the form of an Arabic Quran. The Arabic Quran then becomes more than law or guidance or even a sacred book; it is also disclosure of the Divine Will for all humankind in all places at all times. Arabic becomes not just one among many languages but the key index to salvation, prioritized over any other human language.

History versus Orthodoxy

Does the priority of Arabic then preclude the transmission of the Quranic message in languages other than Arabic? The orthodox view is yes; only in Arabic is the Quran truly the Quran. Arabic was the language of the final revelation, and the Arabic text remains untranslatable. Yet not all those who later heard the Arabic Quran were Arabs or knew Arabic. As Islam spread and many non-Arabs became Muslims, translations, mostly interlinear insertions in the Arabic text, did occur, but they remained few. Only recently have translations proliferated, especially in English.

This staggered process raises a number of further questions: Is the Quran to be judged on the anvil of history, where translation intrudes and recurs? Or must the revealed text always be distilled through a filter of orthodoxy, privileging pristine Arabic and avoiding or degrading other languages? To grasp its message, does one elevate seventh-century Arabic, and by extension Arab origins, across time and space? What of the many Muslims, the majority of a 1.5-billion-person community, who are non-Arab and unacquainted with Arabic, save through the Quran?

Again and again one must ask: which predominates, the anvil of history or the filter of orthodoxy? There is no single, easy answer. Use of Koran rather than Quran is itself a choice of history over orthodoxy; despite the usage of centuries, from the twelfth to the twenty-first, of the name Koran, the orthodox would still say that any reference in any language to the Noble Book, the Word of God in Arabic, must be Quran or al-Quran. Beyond the Quran/Koran choice, the same query applies to the entirety of the Noble Book and to all texts, sacred and profane, that are translated: can any text be translated without sacrifice of the original meaning, and once translated, who judges whether that sacrifice is warranted, the outcome justified, the product edifying?

These queries about translation seemed novel to me in spring 1961. It was then that I took a course on Russian literature in translation at Princeton University. The lecturer was a European literary critic, George Steiner. Focusing on the limits of memory, Steiner lamented the lack of any means to assess a hierarchy of value. In the mind of every translator, according to Steiner, there exists a hierarchy of value among languages. How do these linguistic registers interact in the mind of each person who undertakes to translate, whether he or she is bilingual, trilingual, or multilingual?

The clue is to be found in the Tower of Babel. It was the image of this chaotic space and experience that gave Steiner the title for his classic study: After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation (1975). The Tower of Babel is itself open to opposite interpretations. Many focus on the disaster of Babel. It prefigures the scattering of languages, tribes, and cultures that has led to endless strife and destructive, even cataclysmic warfare. Yet there is another view that favors rather than laments linguistic polyphony. Could one not argue that through the Tower of Babel, and because of the Tower of Babel, the God of the Torah, the Bible, and the Quranthe One who is also Omniscient Creator, the Lord of History and Destinyhas decreed that there be many languages? Might there not be a Divine basis for the healthy diversity of expressiveness that binds as well as divides humankind? Even Holy Writ is ambiguous. The book of Genesis declares: It was called Babelbecause there the Lord confused the language of the whole world. From there the Lord scattered them over the face of the whole earth (Genesis 11:9). And the Quran makes an even stronger claim when it declares:

Next page