The European Quran

Edited by

Mercedes Garca-Arenal

Jan Loop

John Tolan

Roberto Tottoli

Volume

ISBN 9783110702637

e-ISBN (PDF) 9783110702712

e-ISBN (EPUB) 9783110702743

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

2021 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston

Introduction

Cndida Ferrero Hernndez

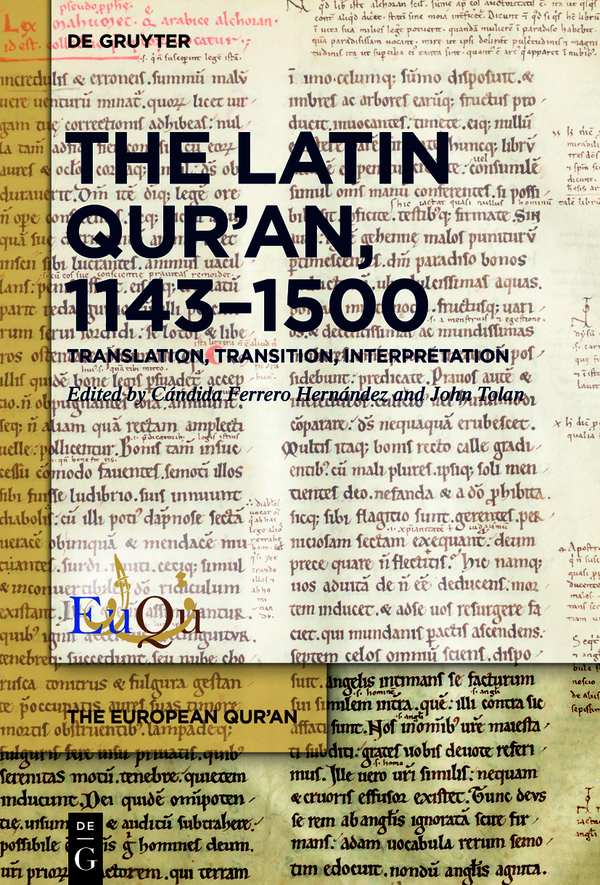

The present volume, The Latin Quran, 11431500: Translation, Transition, Interpretation,

In the eastern Mediterranean, geographical proximity and diverse channels of political and cultural exchange between Christian and Islamic communities early on fostered, among Christians living in that region, an in-depth knowledge of the Quran and the traditions on the life of the Prophet. By contrast, in the western Mediterranean it is not until the twelfth century that we find the first systematic endeavours to study and disseminate with polemical intent the laws and traditions of Islam. Until then, all that was available were an array of legends about the figure of Muhammad, which historians and poets had been circulating since the mid-eleventh century. The Benedictine monk Guibert de Nogent (10551124), author of the Gesta Dei per Francos (1109), remarked that Latin Christendom lacked the sort of solid information on the law of Muhammad that could make for sound refutations of it, himself indicating that he could only relay the information that had reached his ears.

This method of using an Arabic anti-Muslim polemical source was also followed by the Judeo-Converso Petrus Alfonsi, by the abbot of Cluny, Peter of Montboissier, better known as Peter the Venerable (ca. 10921156).

Indeed, as preparations for the Second Crusade (11471149) were underway, the abbot travelled to the Iberian Peninsula (11411143) in order to inspect various Cluniac monasteries and inquire into their finances. Therefore, the abbots journey proved fruitful, not only for the Order of Clunys coffers, but also in terms of the far-reaching intellectual impact it was to have in its own time and after, constituting a decisive event in the intellectual history of Europe, and wherein it is important to highlight the contribution of the expert translators, trained in the finest Latin rhetoric of the twelfth century, and with a wealth of experience in the translation of Arabic scientific texts.

This is not the only difference between their translations, as they both follow different methods: Robert, steeped in the elegant rhetoric of the twelfth century, employs all its figures and turns of phrase, while Marks translation adopts a word-for-word approach.

However, in addition to these full translations of the Quran, it is also important to consider cases where authors provide their own translations of specific ayas and suras, as in the Liber denudationis siue ostensionis uel patefaciens, recommends reading the Quran in order to understand it and, in turn, reject it.

Cardinal Juan de Segovia (1390/51458), which reveal the complex intertwining of Islamic and Christian texts and identities throughout the Hispanic lands.

The sixteenth century marks the consolidation of the printing press, which would enable texts to spread quickly and efficiently, while at the same time ushering in different approaches to Islam, whose apogee in this moment corresponds to the period of Ottoman expansion deep into Europe, and to a mutation in Christian perspectives, imbued with the principles of Humanism and the tools of philology, which together led to the study of Semitic languages, giving rise to the field of Orientalism at European universities and among religious orders. But it is also a time of imperialist policies, from a position of power over newly encountered territories that helped to reconfigure the Orbis terrarum, with new religious interests and polemics at the heart of Christianity, building up to the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, and thus giving Islam a new role within intra-Christian conflicts. In fact, the first printed book containing diverse and numerous texts that amounted to a veritable encyclopaedia of Islam from a European perspective was composed by the Protestant reformer Theodore Bibliander (1543), who argues in his preface to the book in favour of Islams value as a tool in the fight against the Papacy. Apart from the many other texts it contains, what stands out above the rest is the editio princeps of the first Latin translation of the Quran and the rest of the works making up the Corpus Islamolatinum, to which were added the texts written about Islam by the abbot of Cluny following his own reading of the works in the Corpus, thus closing the circle begun in 1143, and enabling Robert of Kettons first Latin translation of the Quran to reach a wider readership. If in the premodern period it had already been profusely read and commented upon in manuscript form, the printed edition was to prove a great success, thus finding its way to a broader and more diverse public.

Indeed, the intense circulation of manuscripts, readings, annotations, interpretations and polemical rewritings during the four centuries that passed from the completion of the first Latin translation of the Quran in 1143 until the publication of Biblianders encyclopaedia in 1543, constitute the material at the heart of this present volume.

Bibliography

Sources

Alfonsus Bonihominis. Disputatio Abutalib. In Alfonsi Bonihominis Opera omnia. Edited by Antoni Biosca i Bas. Turnhout: Brepols (Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis 295), 2020.

Iohannes de Segobia. Prologus Alcorani. Edited by Jos Martnez Gzquez. El Prlogo de Juan de Segobia al Corn (Quran) trilinge (1456) Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch: Internationale Zeitschrift fr Medivistik, 38/2, 2003: 389410.

Iohannes de Segobia. Prologus Alcorani. Edited by Dario Cabanelas. Juan de Segovia y el problema islmico. Madrid: Universidad Complutense 1952. 2nd ed.: Granada: Universidad de Granada, 2007.

Juan Andrs de Xtiva. Confusin o confutacin de la secta mahomtica y del Alcorn. Edited by Elisa Ruiz Garca and Mara Isabel Garca-Monge. Mrida: Barcarrota, 2003.

Latin Translation of the Quran (1518/1621) Commissioned by Egidio da Viterbo. Critical Edition and Introductory Study. Edited by Katarzyna Krystyna Starczewska. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2018.

Liber denudationis siue Contrarietas Alpholica. In Religious Polemic and the Intellectual History of the Mozarabs c. 10501200. Edited by Thomas E. Burman. Leiden: Brill, 1994.

Machumetis Saracenorum principis, eiusque successorum vitae, ac doctrina, ipseque Alcoran [...]. Edited by Theodor Bibliander. Basel: Johannes Opporinus, 1543, 3 vols.

Marcus Toletanus. Alchoranus Latinus, quem transtulit Marcus canonicus Toletanus. Edited by Ndia Petrus Pons. Madrid: CSIC (Col. Nueva Roma, 46), 2016.

Petrus Cavalleria. Tractatus zelus Christi contra Iudaeos, Sarracenos et Infideles. Edited by Martn Alonso Vivaldo. Venetiis: Baretium de Baretiis, 1592.

Raymundus Lullus. Liber de gentili et tribus tribus sapientibus. Edited by scar de la Cruz Palma. Brepols: Turnhout (Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Mediaevalis 264 ROL XXXVI), 2015.

Raymundus Martini. Capistrum Iudaeorum. Edited by Adolfo Robles Sierra. Wrzburg-Altenberge: Echter, 1990, vol. I. Wrzburg- Altenberge, 1993, vol II.