THE YOUNG T. E. LAWRENCE

ANTHONY SATTIN

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

New York & London

For Johnny and Felix, setting out...

Contents

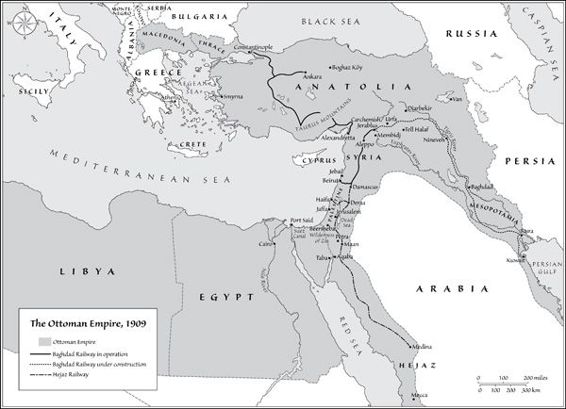

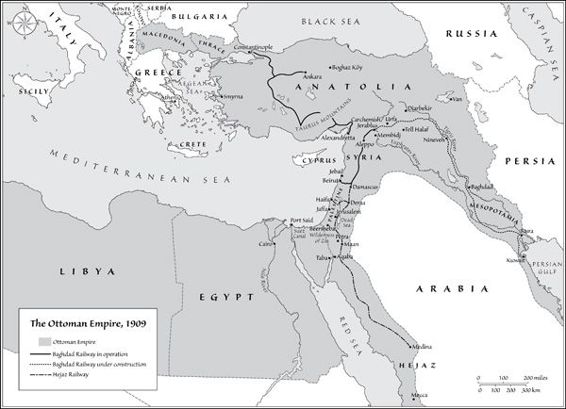

The Ottoman Empire, 1909

Crusader Castle Walk, 1909

The Carchemish Area

The transliteration of Arabic words and the spelling of place names in the region covered by this story is problematic because there is no one system and no international norm. A city such as Aleppo, for instance, is also known as Halep, Halab and Alep, while Damascus is also known as Damas and as-Sham. Another layer of complication has been added by time: some spellings and names have changed over the century since Lawrence and his colleagues wrote them down. Constantinople is now called Istanbul. Beyrout, or occasionally Beyrouth, is now Beirut. The word for castle, qala, appears as kala in Lawrences writing, so I have used it Kalaat, not Qalaat al Kahf. Yet another layer of complication is added by the different usages of Arabs, Turks and others. I have adopted whatever has seemed most reader-friendly. I have not changed any of the archaic spellings if they are still obvious to us today, or if they refer to places most of us have never heard of. Similarly, with the prefixes al- and el-, I have favoured common usage over consistency. My intention, throughout, has been to let the words flow.

All men dream: but not equally. Those who dream by night in the dusty recesses of their minds wake in the day to find that it was vanity: but the dreamers of the day are dangerous men, for they may act their dream with open eyes, to make it possible. This I did.

T. E. Lawrence, Seven Pillars of Wisdom

I love all waste

And solitary places; where we taste

The pleasure of believing what we see

Is boundless, as we wish our souls to be.

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Julian and Maddalo

If I could talk it like Dahoum, you would never be tired of listening to me.

T. E. Lawrence in a letter to George Bernard Shaw, 1927

Prologue

The First Spark

The stories of his adventures and the hardships he endured on that trip would make the most thrilling reading; they would sound like the Arabian Nights.

Fareedeh el Akle

Oxford, August 1914

A YOUNG MAN CROUCHES beside a fireplace and strikes a match. He is in the sitting room of a bungalow at the end of a garden, separated from the main house by a lawn, roses, perhaps also hollyhocks. The solid redbrick house, his family home, sits on a road just north of the centre of Oxford and could stand as a monument to Englishness. Identical to other Victorian houses in the area, it is almost anonymous. The bungalow, which has been purpose-built for the second of the familys five sons, has a small bedroom, electricity, running water and, something of a novelty, a direct telephone line to the main house. The walls are hung with fine green cotton to encourage calm and there is a fireplace for warmth. But it is August, the summer has been good and the weather bright, so there is no need for heating and yet the young man holds the match to papers piled in the grate.

The man is T. E. Lawrence Thomas on his birth certificate, Edward to outsiders, Ned to his family, T.E. to some of his friends, El Aurens to his Arab companions. He has just celebrated his twenty-sixth birthday and war has been declared. The bungalow is his retreat, commissioned while he was studying history at the nearby university and when he needed some personal space. For the past four years, however, he has been an infrequent visitor, passing through in the summer, on one occasion causing a stir when he arrived with two Arab friends. For most of those years, he has been travelling and living in an area marked on his map and he has become an expert on this region as Northern Arabia, an area that includes the countries we know as Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan and Egypt. Northern Arabia, divided into the Ottoman vilayets or provinces of Syria, Palestine, Mesopotamia and Egypt, is the setting for the story that is to unfold.

The fire takes, and pages curl in the grate, become blackened, flame-licked, and give up acrid smoke. He is burning the only copy of a book he has written about his experiences in the East.

Exactly five years later, in August 1919, the Royal Opera House in London was packed, twice a day, with people wanting to hear about the great war hero Lawrence of Arabia. Not long after, when the man himself had changed his name and profession and was trying to disappear (but also, it must be said, popping into the theatre to see himself on the screen), he mentioned this youthful indiscretion book to a friend who had also served in Arabia. It recounted adventures in seven type-cities of the East, he explained, Cairo, Baghdad, Damascus, etc. A queer book about his years of adventure about finding happiness, about love.

The only reason he gave for destroying the manuscript was that it was immature. But that doesnt quite ring true. He had written other works a description of Crusader castles in Syria, for instance, and the diary of a journey he made across the Euphrates River in the summer of 1911. Both of these unpublished manuscripts were immature, both had caused him difficulties, and both were in the bungalow at the end of the garden. So why burn the book of his adventures? A clue lies in the admission of indiscretion and in the outbreak of war.

His brother Frank had already been commissioned into the army and had gone to fight. Another brother, Will, was on his way back from India, intending to enlist. Lawrence knew that soon weeks perhaps he would leave the bungalow, say goodbye to his parents and travel south to London and from there to war. In August 1914, at the very beginning of the conflict, no one had any idea of the slaughter that lay ahead in the Somme, at Ypres, in the Dardanelles and in many other places whose names we might otherwise not know, and which would claim the lives of both Frank and Will the following year. In August 1914, many people expected World War I to be over by Christmas: it was inconceivable that it would last four years, claim eight and a half million lives and bring an end to four empires.

Lawrence had already offered his services to the war effort. He had lived in and travelled around the Middle East for the previous five years and he knew that this would be a conflict unlike any other. He knew, because he had watched it take shape, growing from a small fight in Libya to major battles in the Balkans to a war that would destroy his life. He was certain that he had a role to play in this conflict. In fact, he had already dreamed of the glorious challenge: he would start a new crusade by raising a wave of fighters out of Arabia and rolling them before the breath of an idea, to crash against the walls of Damascus. In so doing, he believed, they would free the Arab lands from Ottoman control. He had already laid his plans. He knew the terrain, the combatants and the tactics that would win the prize of freedom for the people he loved. Now he was watching nations lining up to fight, waiting for the Turks to join the war.

It seems natural, under these circumstances, at some point, if only during the black hours of night, hours he knew well, that he would consider his own mortality, because he might not return from this war. He was certainly aware of that possibility when his brother Frank went to join the 3rd Gloucestershire Regiment. I didnt go to say goodbye to Frank, because he would rather that I didnt, & I knew there was little chance of my seeing him again; in which case we were better without a parting.