Praise for Flame into Being:

Burgesss book never ceases to remind one that Lawrence was a great writer, and that argument about him should always begin from a shared assumption of that greatness.

Frank Kermode in the London Review of Books

It is excellent to see Burgesss sympathetic, passionate and immensely readable biography of D. H. Lawrence back in print. It is a book which sends you back to Lawrences writing with renewed enthusiasm for the man and his work.

Andrew Harrison, director of the D. H. Lawrence Research Centre, University of Nottingham

Wry, profound, often critical, always sympathetic, and always in awe. This book wields the cudgel against Lawrences enemies, and is fairer than Lawrence himself to his friends. As confident in its opinions, and as quotable, as Lawrence himself, it makes the strongest possible case for the idea that whatever life is, we need the eloquence of his allegiance to it .

Catherine Brown, editor of D.H. Lawrence and the Arts

Burgess responded to the siren call of a geniuss centenary with handsome tributes in print, film and song. Flame into Being is a neglected classic of critical biography: irreverent to literary conventions as was Lawrence himself and as attentive to the rhythms of life and art. This highly readable, readerly account exemplifies a critical mode that speaks to, and from, the heart of a writers craft.

Susan Reid, editor of the Journal of D. H. Lawrence Studies and author of D. H. Lawrence, Music and Modernism

Some writers write to live. In these pages Burgess seeks to show that Lawrences very life was the flame that fed and refined all that was best in his writing.

Malcolm Gray, chair: The D.H. Lawrence Society

also by Anthony Burgess

and published by Galileo:

HERE COMES EVERYBODY

An Introduction to James Joyce

for the Ordinary Reader

FLAME INTO BEING

The Life and Work

of

D. H. LAWRENCE

by

Anthony Burgess

Galileo Publishers, Cambridge

First published by William Heinemann 1985

This new edition published 2019

by Galileo Publishers

16 Woodlands Road, Great Shelford, Cambridge,

UK, CB22 5LW

www.galileopublishing.co.uk

Galileo Publishers is an imprint of Galileo Multimedia Ltd.

ISBN 978-1-903385-92-0

Text 1985, 2019 by Anthony Burgess

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Cover design by NamdesignUK

All rights reserved.This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Printed in the EU

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Per Liana

Contents

Preface

This brief book had its origins in the intention to write a book even briefer a centennial tribute to D. H. Lawrence which should be a sort of payment of a debt. We all, readers of books and writers of them, are grateful to literary genius for enriching our lives, but the writer has the duty and privilege of expressing his gratitude through his craft. Inevitably, as with all debts, he puts off payment, but he cannot evade the final notice of a centenary. In 1964, the quatercentenary of Shakespeares birth, I produced at last a novel on the life and loves of the greatest English poet after many years of indecisive brooding. It might have been a better novel if I had prolonged its incubation, but the clock whirred and got ready to strike, and it was clear to me that if the book was not published on 23 April 1964 it might never reach publication at all. In 1982, James Joyces centenary, there was broadcast simultaneously from Dublin and London my musical version of Ulysses, a tribute which some critics heard as a disparagement. I have, with the same expectation, set four of Lawrences poems to music. I have also made a television film about him. I proposed also a brief homage to him in the medium which is my primary mtier, and this book is the result.

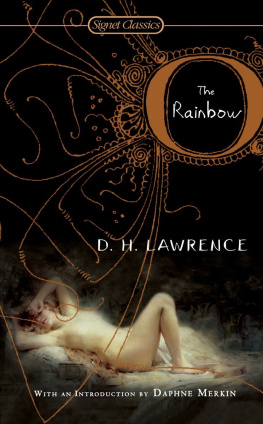

I had wished merely to discuss certain selected works of his, but I discovered that it was not possible to separate Lawrences work from his life. One could not choose a segment of his life which, God knows, was short enough and therefore one could not choose a segment of his work. What you have here, then, is a brief literary biography which may serve to introduce the man and his writings to those who know nothing of either with the exception, naturally, of Lady Chatterleys Lover and the scandal which still clings to its author or, knowing something of both, would like to know more. Lawrence wrote a remarkable amount in a life truncated by tuberculosis, and the reading of what he wrote should not be a matter of random choice: he needs to be read entire, and in an order dictated by the vicissitudes of his life. This may well be true of all imaginative writers, but it is overwhelmingly true of Lawrence.

I mentioned a debt, but this is not a literary debt at least, not in the sense that I ever wished to write like Lawrence or that I have ever recognised in my own work; such as it is, any trace of his influence. There is a great disaffinity of culture and even blood between myself and him. I, mostly Irish, brought up in the north of England as a Catholic, of a pub and shop background, confront a Nonconformist Anglo-Saxon from the Midlands, proud of his puritanism, drawn to pre-Christian gods, the son of a miner. But I admire him as the sort of good Englishman I can never myself be, I admire his intransigence, and I sympathise with his sufferings on behalf of free expression. A hundred years after his birth, I consider that he has triumphed over his enemies (though, in the English-speaking world, one can never be sure), and that he stands for that fighting element in the practice of literature without which books are a mere decor or a confirmation of the beliefs and prejudices of the ruling class. I say at the end of my book that literature is essentially subversive, and that Lawrence is a witness (or martyr, which means the same thing) for that truth. He is a powerful exemplar of those virtues which all who write for a living, and at the same time to promote a pleasure in living, like to think inheres in the practice of their craft or art energy, doggedness, desperate sincerity, delight in the daily struggle to make words behave.

In old age I wake up with surprise to find myself in the situation that Lawrence chose in his youth namely, that of a British writer in exile (married, incidentally, to a foreign aristocrat), who feels more at home by the Mediterranean than by the Thames or the Irwell, using foreign languages more than English in daily discourse, trying to hear English and see the English the more clearly for not living with them. Voluntary expatriation never goes down well with my, and Lawrences, fellow-subjects of the British crown: the novelist who lives abroad is trying to evade taxation or bad weather or both (in fact, he evades neither). What he is really trying to do is to get out of the narrow cage which inhibits the British novel, to acquire a continental point of view, to avoid writing about failed love affairs in Hampstead. He is also fulfilling the writers right to live where he wishes, so long as he can get on with his work. The thing to remember about Lawrences exile is that it enabled him to serve England, or at least Englands literature, far better than if he had stayed at home. As a preface is no more than a discardable lizards tail, though fixed frontally, it may accommodate fancies that would be improper in the body of the work (which, having a certain organic life, is a sort of animal). Lawrence was the only great British writer to celebrate a centenary in 1985, a year devoted to musicians and, most of all, to Handel, who was born in 1685. There is a certain piquancy in the chance concelebration of the birth of a great German composer who became British and that of a great British writer who, marrying a German, abandoned Britain. Handel was adored by the British (when they were not adoring The Beggars Opera ) ; Lawrence was reviled by them. It would be highly fanciful to seek any community of aim and achievement in George Frideric and David Herbert. But I remember a passage in Samuel Butlers The Way of all Flesh where the narrator, seeing and hearing farm labourers singing a hymn in a country church, finds the tune of Here the ploughman near at hand/Whistles oer the furrowed land, from Handels setting of Miltons LAllegro, getting into his head. He comments: How marvellously old Handel understood these people! Read The White Peacock and Sons and Lovers and The Rainbow to see how marvellously Lawrence understood them too. All art is concerned with penetrating into the heart of life. Both Handel and Lawrence knew this, and they performed some marvellous acts of penetration.