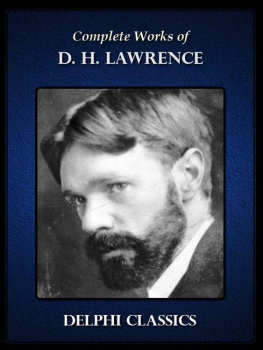

David Herbert Lawrence (18851930) was born in the mining village of Eastwood, near Nottingham, England. His father was an uneducated miner; his mother, a former schoolteacher. Lawrence began his first novel, The White Peacock (1911), while attending Nottingham University. In 1912, he ran away with Frieda von Richthofen, the wife of one of his professors. They were married in 1914. Suffering from tuberculosis, Lawrence was in constant flight from his ill health, traveling through Europe and around the world by way of Australia and Mexico, settling for a while in Taos, New Mexico. Lawrence and Frieda returned to Europe in 1925. Among his more than forty volumes of fiction, poetry, drama, criticism, philosophy, and travel writing are Sons and Lovers (1913), The Rainbow (1915), Women in Love (1920), Studies in ClassicAmerican Literature (1923), The Plumed Serpent (1926), and Lady Chatterleys Lover (1928).

Daphne Merkin is an essayist, novelist, and literary critic. She is a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine and Elle, and she writes for Slate, Book Forum, and many other publications.

SIGNET CLASSICS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

Published by Signet Classics, an imprint of New American Library,

a division of Penguin Group (USA) LLC

Introduction copyright Daphne Merkin, 2009

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA

ISBN 978-0-698-19669-8

If you purchased this book without a cover you should be aware that this book is stolen property. It was reported as unsold and destroyed to the publisher and neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this stripped book.

Version_1

Introduction

The first thing to be said about D. H. Lawrenceif only to face the reality head-on, before it spreads like an unspeakable but invincible conviction leaking from the readers subconscious onto the pageis that there is something deeply disturbing about him. It is impossible, that is, to respond to his febrile imagination and equally febrile prose with neutrality, the way one approaches so many other writers: liking some more than others; preferring the early accessible style of Henry James to the later involuted version; warming up to a muscular voice, like Dickenss, over a more lyrical one, like Virginia Woolfs.

Lawrences writing defies such familiar literary signifiers as original or daring. It is sui generis: Take him or leave him, he sounds and thinks like no one else. It makes sense, therefore, that his work has been hotly debated by even the most sophisticated readers since it first saw the light of day, with the publication in 1911, when Lawrence was twenty-six, of his first novel, The White Peacock. Already here it was clear that the subject that preoccupied the young author with the intense blue eyes and flaming red beard (his full name was David Herbert Lawrence but he began using the initials DHL or D. H. Lawrence as his signature already as an eighteen-year-old) was the fraught and culturally defended-against one of sexual desirewhat he would describe years later, shortly before he died, as the full conscious realization of sex. Virginia Woolf, in a review of one of Lawrences minor novels, The Lost Girl, noted that the problems of the body were insistent and important for him; sex for Lawrence had a meaning which it was disquieting to think that we, too, might have to explore.

The disquiet has taken two directions: There have always been those, like the churchy British critic F. R. Leavis, who saw outright genius in him; in his (these days mostly ignored) seminal work, The Great Tradition, Leavis considered Lawrence to be far more of a creative innovator and master of language than James Joyce. And there have always been those, like T. S. Eliotwho remarked that the author of Lady Chatterleys Lover seems to me to have been a very sick man indeedwho read his work as the ravings of a lunatic, possessed of a psychological disorder that went under the disguise of literature.

Indeed, although we often think of creative people as being crazyin the sense of different, unaccountable, out of the ordinaryLawrences offness is a primary aspect of his work, part and parcel of the visionary as well as the curiously moralizing impulse in him. (The critic Diana Trilling got close to the intuitive truth about his character when she observed in her introduction to the 1958 collection of his letters that so much a poet, he yet insists that we read him as a preacher.) Lawrences interest is neither in capturing the established order of things nor in subverting it; rather, he is out to bring us news (whether more or less lucid depends on the individual work and the subjective response of the reader) of different human possibilities altogether. As John Worthen describes it on page 83 of his superb biography, D. H. Lawrence, The Life of an Outsider: The writer and the man wanted to discover new, post-religious ways of describing fulfillment: a state of self (or being) in which detached consciousness and body were not fatally divided but somehow brought together.

My great religion, Lawrence wrote in a 1913 letter, is a belief in the blood, the flesh, as being wiser than the intellect. We can go wrong in our minds. But what our blood feels and believes and says, is always true. (This from a man who several years earlier had gotten into an argument with a friend who insisted that women had pubic hair and who had listed sex matters on a list of things for which he did not much care.) As much of a disbeliever in ordinary religious precepts as he may have beenhe was convinced there was no personal GodLawrence devoutly believed in his own philosophical effusions. It is from this perspectivecall it primitive, neo-Fascist, sublime, or ridiculousthat he chooses to write. It is also this perspective that underlies the often peculiar literary effects he aims for and that has led over the years to the many charges that have been brought against him. English obituaries following upon Lawrences death in 1930 referred variously to his pathological traits and to the fact that he wrote with one hand always in the slime, while his current decline both in and out of academia casts him as something of a politically incorrect, antediluvian jokemisogynistic, colonialist, racist, homophobic, way too florid, and embarrassingly unironic.

The Rainbow, published in 1915, when Lawrence was thirty, was his fourth novel. It had been preceded by a largely forgotten effort called The Trespasser

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA

REGISTERED TRADEMARKMARCA REGISTRADA