Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To Ophelia Field

I always feel as if I stood naked for the fire of Almighty God to go through me One has to be so terribly religious to be an artist. I often think of my dear Saint Lawrence on his gridiron, when he said Turn me over, brothers, I am done enough on this side.

D. H. Lawrence, Letters, 25 February 1913

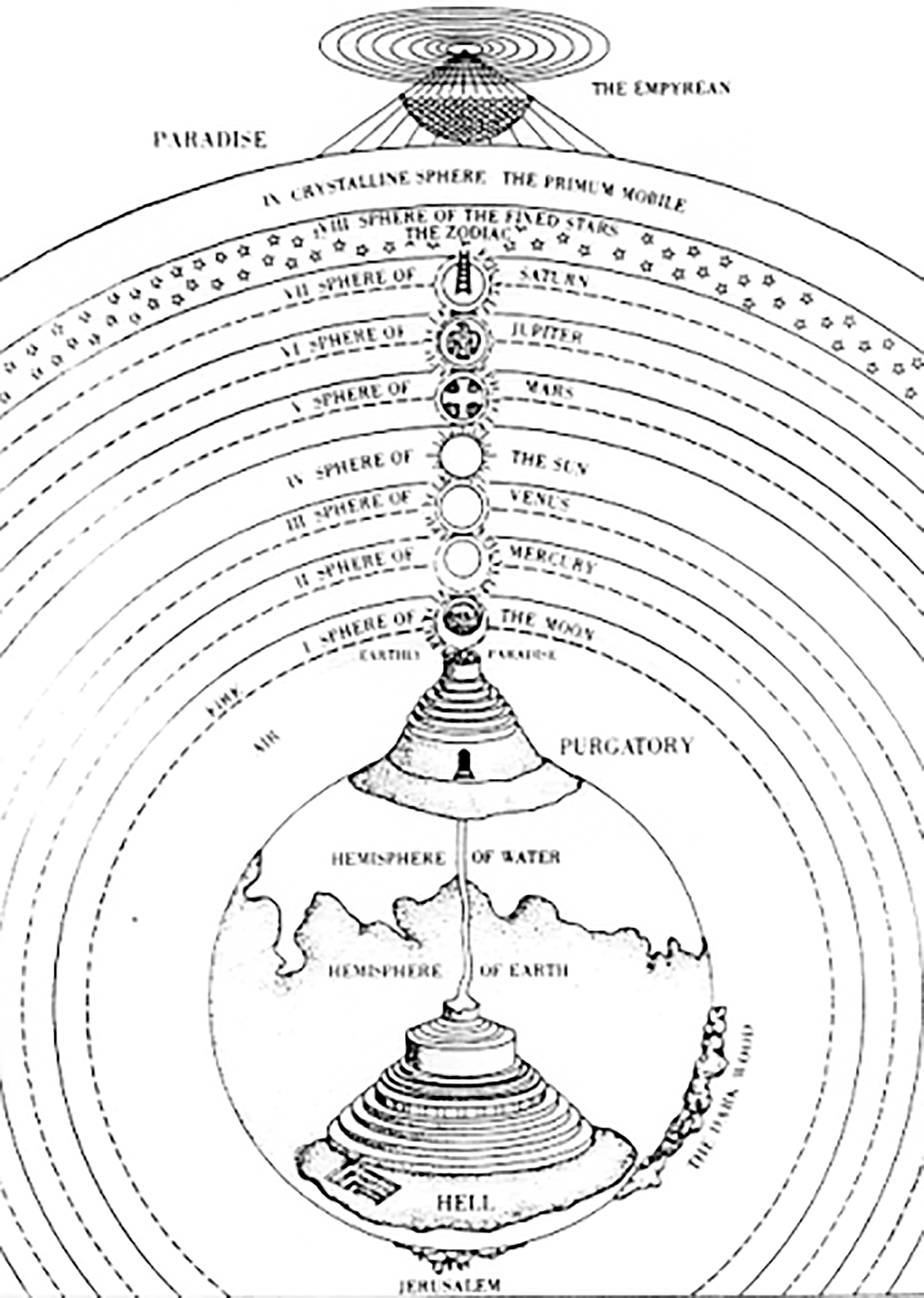

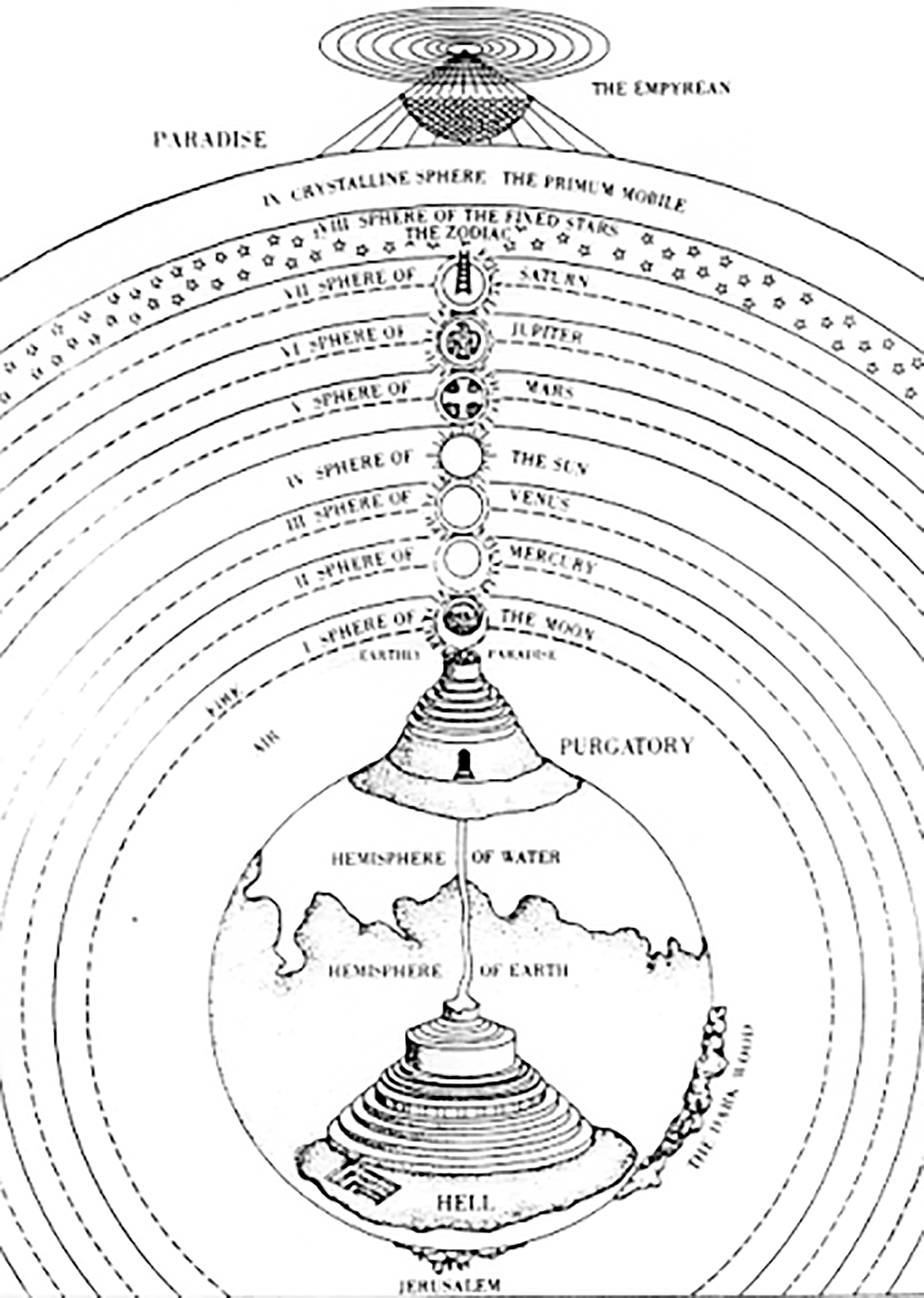

Medieval Cosmology

Isnt it remarkable how everyone who knew Lawrence felt compelled to write about him? Why, hes had more books written about him than any writer since Byron!

Aldous Huxley, The Paris Review (1960)

Never trust the teller, trust the tale. The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.

D. H. Lawrence, Studies in Classic American Literature (1923)

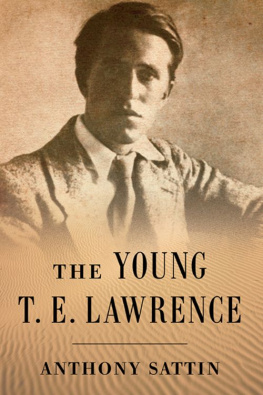

Everyone who knew him told tales about D. H. Lawrence, and D. H. Lawrence told tales about everyone he knew. The tales that Lawrence told about his friends, who consequently became his enemies, can be found in his fiction, and the tales that his friends and enemies told about Lawrence can be found in the numerous memoirs and portraits that appeared after his death, and the spate of novels which feature a thin and bearded prophet. He also, again and again, told tales about himself: no writer before Lawrence had made so permeable the border between life and literature, or held so fast to his native right to put everything he was into a book.

Burning Man is a triptych of self-contained biographical tales which take as their subject three versions of Lawrence. My focus is his middle years, the decade of superhuman energy and productivity between 1915 when The Rainbow was prosecuted, and 1925 when he was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Inferno is set largely in England, Purgatory is set largely in Italy, and Paradise takes place largely in the American Southwest. I say largely because after 1912 Lawrence, who was a different man in every place, was never in the same place for more than a few months; he and his wife Frieda roamed the world like gypsies and slept like foxes, in dens. Because Lawrence believed there was no progress without contraries, each of these tales sees him in battle, and because he was always in battle, I have selected those battles that have been granted the least attention. In doing so I give major roles to those figures otherwise assumed to be minor and minor roles to those figures generally considered major; episodes and experiences that earlier biographers have passed over in a paragraph are here placed centre stage. I look closely at the novels because they mattered to Lawrence and tell us who he was at the time of writing, but I do not consider them his major achievement. When F. R. Leavis placed The Rainbow and Women in Love on his Great Books List, he consigned the best of Lawrence to the periphery where it has remained ever since, so that readers today have no sense of either his range or the preternatural strangeness of his power. One aim of this book is to reveal a lesser-known Lawrence through introducing his lesser-known works.

Both censored and worshipped in his lifetime, Lawrences afterlife has been one of peaks and troughs. If there was one person everybody wanted to be after the war, to the point of caricature, said Raymond Williams, it was Lawrence. In 1960, after Penguin had been tried at the Old Bailey for issuing an unexpurgated edition of Lady Chatterleys Lover, Lawrence was hailed as the mascot of the sexual revolution, but when, in 1969, Kate Millet skewered him in Sexual Politics for his submissive heroines and bullying heroes, he became one of those figures whose name triggers a psychological lockdown.

Lawrence is still on trial. When I was growing up in the 1980s my mother wouldnt have his novels in the house and my (female) tutor at university refused to teach him. Being loyal to Lawrence, especially as a woman, has always required some sort of explanation, so here is mine. Like many readers, I came to him as a teenager and knew him only as a writer of fiction. Not all of it was good and not all of it was sane, but there was still nothing to compare. He asked the same questions as I did and I liked his fierce certainties: his belief in the novel as the one bright book of life, his belief in himself as right and the rest of us as wrong, his insistence that the unconscious was an organ like the liver; I liked the fact that his women were physically alive and emotionally complex while his men were either megaphones or homoerotic fantasies, that he cared so much about the sickness of the world, that he saw in himself the whole of mankind; I liked his solidarity with the instincts, his willingness to cause offence, his rants, his earnestness, his identification with animals and birds, his forensic analyses of sexual jealousy, the rapidity of his thought, the heat of his sentences, and his enjoyment of brightly coloured stockings.

The Lawrence I have returned to in my own middle years, this time as a biographical subject, is composed of mysteries rather than certainties. Where I once found insight, I now find bewildering levels of naivety; for all his claims to prophetic vision, Lawrence had little idea what was going on in the room let alone in the world. His fidelity as a writer was not to the truth but to his own contradictions, and reading him today is like tuning into a radio station whose frequency keeps changing. He was a modernist with an aching nostalgia for the past, a sexually repressed Priest of Love, a passionately religious non-believer, a critic of genius who invested in his own worst writing. Of all the Lawrentian paradoxes, however, the most arresting is that he was an intellectual who devalued the intellect, placing his faith in the wisdom of the very body that throughout his life was failing him. Dismantle his contradictions, however, and you take away the structure of his being: D. H. Lawrence, the enemy of Freud, impressively defies psychoanalysis.

How can biography do justice to Lawrences complexities? Just as writers of fiction might provide a disclaimer declaring that what follows is a work of imagination not based on real characters, and writers of non-fiction might provide a disclaimer declaring that what follows is not a work of imagination and very much based on real characters, I should similarly state that Burning Man is a work of non-fiction which is also a work of imagination. I should further declare that I am unable to distinguish between Lawrences art and Lawrences life, which was equally a work of imagination, and nor do I distinguish Lawrences fiction from his non-fiction. I read his novels, stories, letters, essays, poems and plays as exercises in autofiction, which genre he pioneered in order to get around the restrictions of genre. Art for my sake, he quipped, but he was being entirely serious. Accordingly, his letters are stories, his stories are poems, his poems are dramas, his dramas are memoirs, his memoirs are travel books, his travel books are novels, his novels are sermons, his sermons are manifestos for the novel, and his manifestos for the novel, like his writings on history, his literary criticism and the tales in this book, are accounts of what it was like to be D. H. Lawrence.

![D. H. Lawrence [Lawrence - Sons and Lovers [Annotated Version]](/uploads/posts/book/61295/thumbs/d-h-lawrence-lawrence-sons-and-lovers.jpg)