ALSO BY FRANCES WILSON

Literary Seductions

The Courtesans Revenge

THE BALLAD OF DOROTHY WORDSWORTH

FRANCES WILSON

FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX

NEW YORK

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York 10011

Copyright 2008 by Frances Wilson

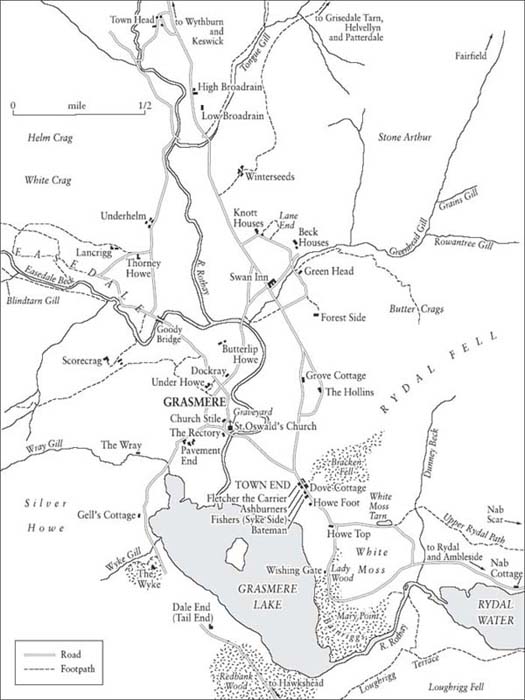

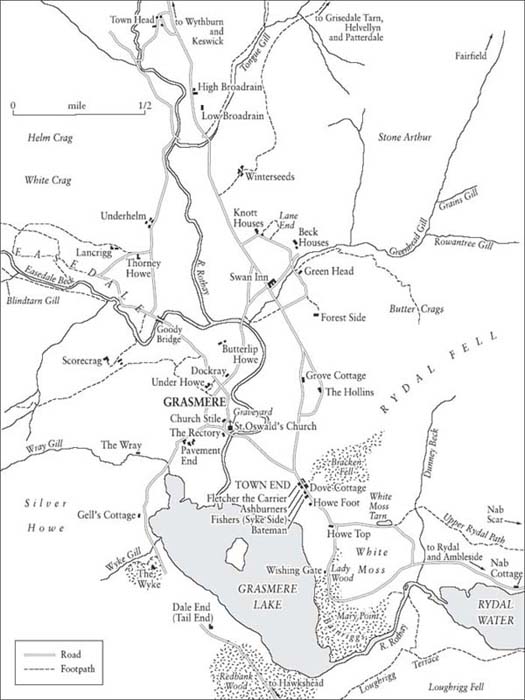

Map copyright Andrs Bereznay

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Originally published in 2008 by Faber and Faber Limited, Great Britain

Published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

First American edition, 2009

Owing to limitations of space, illustration credits appear on page 317.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Frances, 1964

The ballad of Dorothy Wordsworth : a life / Frances Wilson. 1st American ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Originally published in 2008 by Faber and Faber Limited, Great BritainT.p. verso.

ISBN-13: 978-0-374-10867-0 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-374-10867-6 (alk. paper)

1. Wordsworth, Dorothy, 17711855. 2. Wordsworth, William, 17701850Family. 3. Authors, English19th centuryBiography. 4. Women and literatureEnglandHistory19th century. I. Title.

PR5849.W55 2009

828'.703dc22

[B]

2008041263

Designed by Michelle McMillian

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

In memory of my own aunt Dorothy,

and of my grandmother Margery

Mine eyes did neer

Rest on a lovely object, nor my mind

Take pleasure in the midst of happy thoughts,

But either She whom now I have, who now

Divides with me this loved abode, was there,

Or not far off. Whereer my footsteps turned,

Her Voice was like a hidden Bird that sang;

The thought of her was like a flash of light

Or an unseen companionship, a breath

Or fragrance independent of the wind;

In all my goings, in the new and old

Of all my meditations, and in this

Favourite of all, in this the most of all.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH , Home at Grasmere

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

The opening lines of the Grasmere Journals, 26

The back cover of the first notebook of the Grasmere Journals, 31

Racedown, drawing by S. L. May, 78

Scullery maid, drawing by John Harden, 135

Daffodil ( Narcissus pseudo-narcissus L.), by Walter Hood Fitch, 177

Blotting paper in the Grasmere Journals, 203

The Grasmere Journals, May 29, 1802, 209

Swallow, by Thomas Bewick, 217

Entry for October 4, 1802, in the Grasmere Journals, 234

The road to Brompton from Gallow Hill, sketch in the Grasmere Journals, 240

Final page of the Grasmere Journals, 260

Rydal Mount, drawing by Dora Wordsworth, 269

Dorothy in a wheelchair, drawing by John Harden, 1842, 275

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

In order to distinguish Dorothy Wordsworths writing in the Grasmere Journals from that of her other journals or her letters, and so as not to crowd the text with too many quotation marks, I have italicized the words, passages, and entries I quote from this source.

THE BALLAD OF DOROTHY WORDSWORTH

Introduction

CROSSING THE THRESHOLD

A wedding or a festival,

A mourning or a funeral.

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH , Ode: Intimations of Immortality

in our life alone does Nature live

Ours is her Wedding-garment, ours her Shroud!

SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE , Dejection: An Ode

S he can stand it no longer. When she looks from her window at the two men running up the avenue to tell her that the wedding is over, she throws herself down on the bed, where she lies in a trance, neither hearing nor seeing. Earlier that morning the groom had entered her room and she had removed the ring, which she had been wearing all night, and handed it back to him with a blessing. He had then returned it to her finger, blessing it once more, before leaving for the church to bind himself to another. When she is told by the brides sister that the newlyweds are coming, she somehow rises from her bed and finds herself flying down the stairs and out the front door, her body moving against her own volition, not stopping until she is in the arms of the groom. Together they cross the threshold of the house, where they wait to greet the bride.

Dorothy Wordsworths journal entry for October 4, 1802, describes her brother Williams marriage to Mary Hutchinson from the perspective of her bedroom at Gallow Hill, the Hutchinsons Yorkshire farm, where she waited for the couple to return from the local church at Brompton. She was too distraught to attend the ceremony herself. For readers of her journals, Dorothys account of Williams wedding morning comes as a surprise, and not only because of the peculiar early-morning ceremony performed between the brother and the sister and the intensity of her physical response to the event. It strikes a new tone in her writing: after two and a half years of recording what she sees, she now records what she feels about something she has not seen, and it is typical of Dorothy Wordsworth that this long-awaited focus on herself comes just as she is going out of focus, slipping into a semiconscious state as one chapter of her life closes and the next begins.

Following her description of Wordsworths wedding, Dorothys journal seems to lose its purpose. One of her final entries, made a few months later in the new year not long after she had turned thirty-one, has her resolving to keep the project going in a fresh notebook bought during the summer in France: I will take a nice Calais Book & will for the future write regularly &, if I can legibly, so much for this my resolution on Tuesday night, January 11 1803. Now I am going to take Tapioca for my supper, & Mary an Egg, William some cold mutton, his poor chest is tired . Six days later, her final entry, headed Monda[y] , is left blank. In many cases, people turn to their journals when there is nowhere else to turn, when they need to divide themselves into two in order to talk. But in the case of Dorothy Wordsworth, it was when her life alone with her brother was shattered that she stopped writing, as if writing and William were bound up with one another.

This is the story of four small notebooks whose contents Dorothy Wordsworth never meant to be published, and which have become known as the Grasmere Journals. In tightly compressed entries that are mostly regular and mostly legible, they describe a routine of mutton and moonscapes, walking and headaches, watching and waiting, pie baking and poem making. Their style, at times pellucid, at times opaque, lies somewhere between the rapture of a love letter and the portentousness of a thriller; the tight, economical form they adopt is that of the lyric, but in the grandness of their emotions they are yearning toward the epic. The quickly scribbled pages catch the sights and sounds that other eyes and ears miss: the dancing and reeling of daffodils by the lakeside, the silence of winter frost on bare trees, and the glitter of light on a sheeps fleece. They record the love between a brother and a sister, and climax with Dorothys strange fits of passion, to use Wordsworths enigmatic phrase, on the morning of his wedding.

The two and a half years covered by her Grasmere Journals would earn Dorothy Wordsworth the reputation of being, as Ernest de Selincourt, one of her earliest editors and biographers, puts it, probably the most remarkable and the most distinguished of English prose writers who never wrote a line for the general public. The fact that she is one of our finest nature writers, that her phrases and descriptions were lifted and used by both Wordsworth and Coleridge, and that scholars refer to her for background material on her brothers most creative period directs us away from the startling originality of her voice and the strangeness of the story that reveals itself.

Next page