Thank you for downloading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

We hope you enjoyed reading this Scribner eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Scribner and Simon & Schuster.

C LICK H ERE T O S IGN U P

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

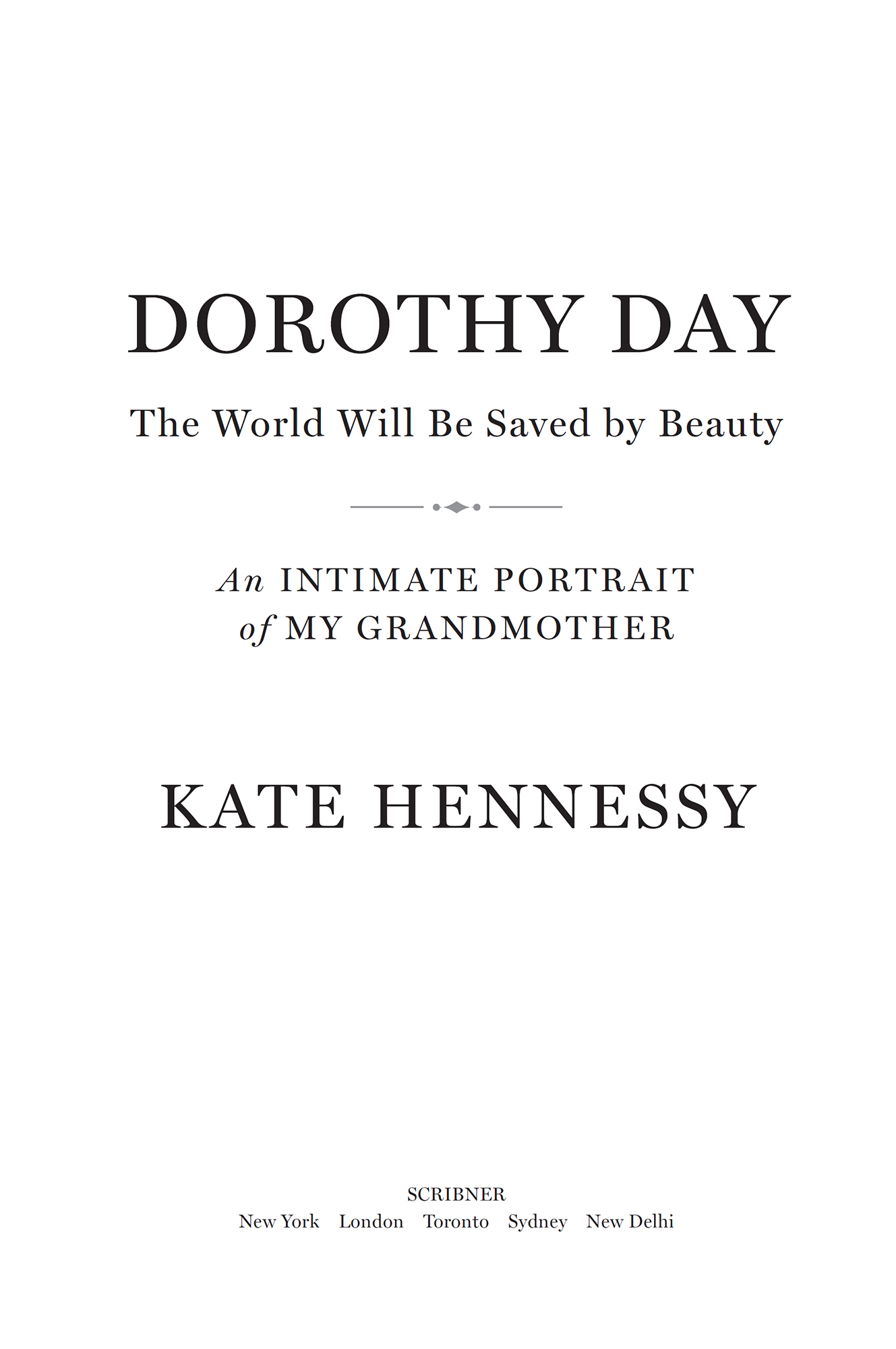

Copyright 2017 by Catherine Hennessy

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition January 2017

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Jill Putorti

Jacket design by Jess Spataro

Jacket photo courtesy of the author

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-1-5011-3396-1

ISBN 978-1-5011-3398-5 (ebook)

In memoriam Tamar Teresa Batterham Hennessy

CONTENTS

PREFACE

I n the last years of her life, my grandmother often woke up hearing in her mind the words from her beloved Dostoyevsky: The world will be saved by beauty. Of all the words she wrote, of all the quotes she loved to repeat, of all the advice and comfort she gave to countless people, in all five of her books and fifty years of her column, and in a lifetime of diary- and letter-writing, this is what has come to give me the most hope. For if, after years of struggle, weariness, and a sense of deep and abiding failure, she believed in salvation through beauty, then how can we not listen?

I discovered this aspect of my grandmother while reading her diaries. They were published two weeks after my mothers death, but it took almost a year before I could bring myself to open the book. Then, once opened, I couldnt put it down. It was as if I, dying of thirst, were given a long, cold drink from the purest of wells. And as I read, I felt a growing need to add another layer to this tale, not only to portray the grandmother I knew and her daughterher only child, Tamarbut also to somehow bring my grandmother and mother together in ways they hadnt been able to achieve while they lived.

On the morning after I finished reading I lingered in that half-asleep state where both dreams and reality take on a different quality altogether. That in-between state where you sometimes hear a voice you are certain is from someone in the room calling your name, and you wake up saying, Yes, what is it? but no one is there. My dream was brief, as dreams of this kind areno beginning or end, just a flash containing all I needed to know. And in that moment I felt, sure and true, the knowledge of both Tamars and Dorothys lives with all their experiences and memories, and I was overcome by this knowing. I felt the weight and the miracle of their lives, and I wondered if I were strong enoughwise enoughto tell this story. But havent I been working on it all my life, living in their wake and stumbling along trying to make my own way?

And isnt this my history also? One of the elements of what makes a person extraordinary, I have come to believe, is when their inner and outer lives are in accord. When what they do in the world is what their innermost being leads them to do. This is why the history of the Catholic Worker is the history of my mother, the history of the relationship between my mother and grandmother, and the history of my family.

* * *

The winter following my grandmothers death was bone-shivering, teeth-achingly cold, the temperature hovering between twenty and thirty degrees below zero night after night. At the time, my mother lived with her small black dog in a hand-built cabin on the edge of the woods. She was alone and grieving, and yet she turned to meshe was fifty-four and I was twentyand in an effort to help us both through this dark time, she and I began a discussion about her mother. These talks were not often easy to follow; their paths could be just as elusive as Tamar was herself. She was unfocused and uncollected. She jumped from thought to thought, while I tried to follow her hints and allusions or the sentences she couldnt bring herself to finish, telling me her story in the grab-bag way she hadan image, a thought, a sparkle and flash of laughter, a retort of anger, regret, or loss.

We continued our conversations on the first anniversary of Dorothys death while staying at the Catholic Workers beach cottage on Staten Island, New York. And then in a house in the small Vermont town of Springfield, where my mother moved from her cabin, the neighborhood rough but full of poor, working-class families, just as Tamar liked it. Again and again we returned to this discussion until the last weeks of her life twenty-seven years later.

Many writersscholars, historians, and theologianshave chosen to tell the story of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker, the movement she began in the 1930s grounded in performing the works of mercy, and that still exists today, decades after her death. But it seems to me that those who knew her best are often the ones most fearful of trying to write about her in all her complexity, richness, and contradictions. Tamar greeted each new book or film about her mother with fatalism, yet she couldnt stay away, and she couldnt keep from being disappointed.

Then, when such a person as Dorothy Day is your grandmother, an examination of her life isnt an intellectual, academic, or religious exercise. For me, it is nothing less than a quest to find out who I am through her and through Tamar. It is a quest to save my own life, though I dont yet know what this means. (Seamus Heaney once said that in his poetry he wrote about those moments he sensed held greater meaning within, even though he might not ever find out what the meaning was.) And I see this quest as not only for me or for my family but for anyone who senses that greater meaning and desires to explore it. There was a group of children who grew up at the Worker in the sixties and seventies who called Dorothy Granny, as my siblings and I do, though they were not related to her, and this is as it should be. We all need to live our lives as if we are Dorothys children and grandchildren, being comforted and discomforted by her as she invites us to be so much more than how we ordinarily see ourselves and, perhaps more important, how we see each other.

Dorothy said there was never a time when she wasnt writing a book or thinking of writing a book; whereas Tamar wasnt a writer and had difficulty expressing herself in any medium. Dorothy was a talker, and my husband was too, she said. That was enough. But there did come a time when she felt the desire to write. When her father, Forster Batterham, died four years after Dorothy, Tamar discovered in his apartment letters Dorothy had written to him in the 1920s and early thirties. In them Tamar finally could read of the love and longing her mother felt for this silent man, so much like his daughter. In them Tamar could once again see her mother, the Dorothy Day she so loved and who seems in danger of being lost to the worlda woman of great joy and passion, humor, and love of beauty. Tamar grieved the loss of this vibrant woman to the annals of hagiography and the desire to see her as a saint, and at times to Dorothys own nature, especially during her severe and pious stage, as Tamar called it. In these letters Tamar found what she had longed forlove between her mother and father, Dorothy the saint and Forster the scientist, the two halves of her heart. And after reading these letters, she wanted to show the world this part of the story, her story.

Next page