Contents

Guide

Dedicated to Steven Roser and Thomas Orefice and to Phil Runkelscholar, activist, and archivistwho has done more than anyone else to keep alive the memory of Dorothy Day and to expand and deepen our understanding of this remarkable woman

INTRODUCTION

DOROTHY DAY: AN AMERICAN PARADOX

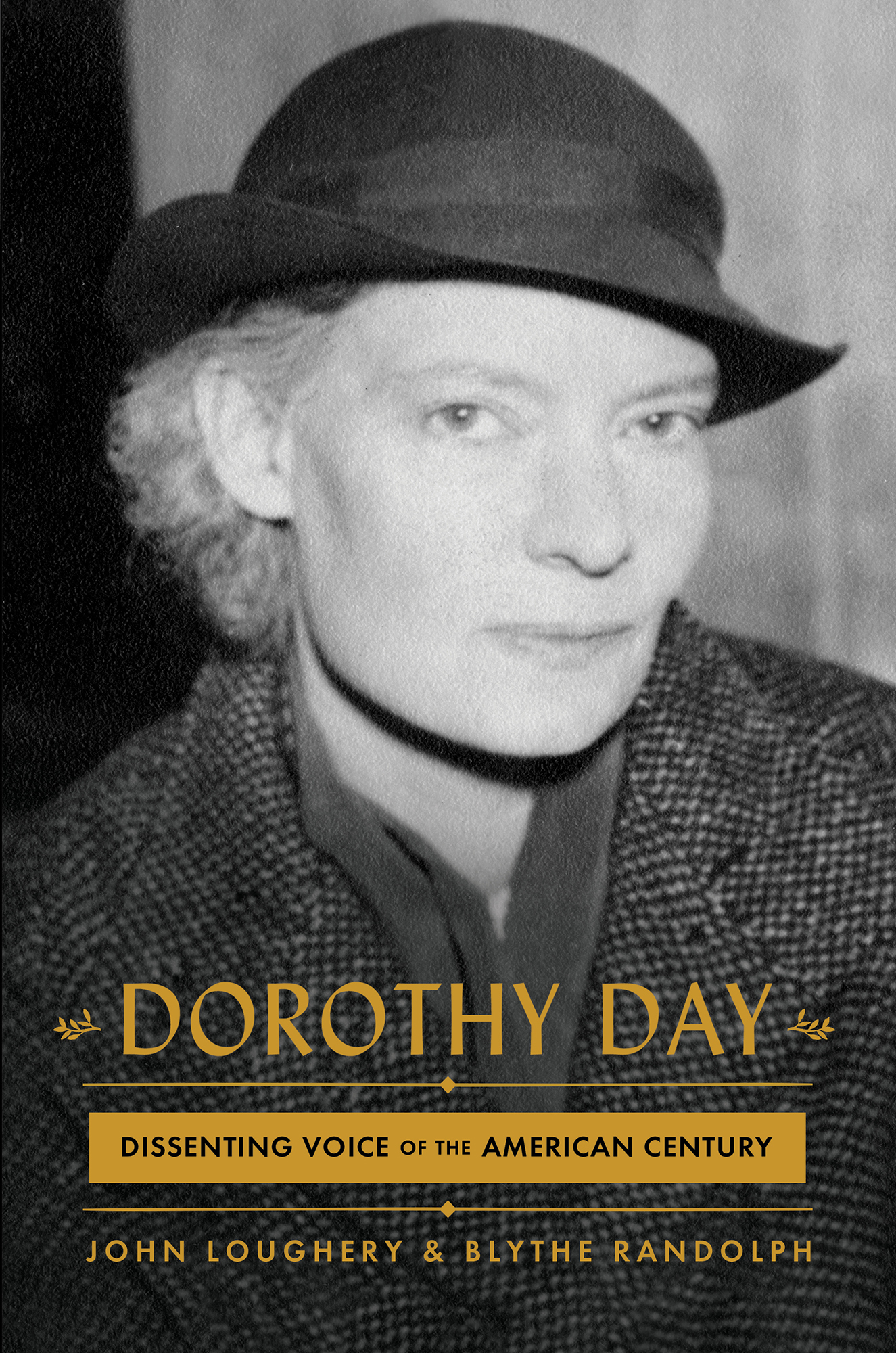

A NY CHRONICLE OF A MERICAN HISTORY today includes the considerable number of women of independent vision who made a mark on the modern world and raised important questions about power, economics, national identity, and social justice. Many of those womene.g., Margaret Fuller, the Grimk sisters, Jane Addams, Ida B. Wells, Margaret Sanger, Frances Perkins, Rosa Parks, Rachel Carson, Jane Jacobshave been the subject of fresh biographies and renewed, appreciative attention in recent years. Dorothy Day (18971980) is a more difficult figure to encompass.

A convert to Catholicism in her twenties, Day was the cofounder of the Catholic Worker movement, a group of autonomous communities across the country (numbering over a hundred today) that provide food and shelter to the homeless and a platform from which to remind Americans that the American Dream has not been an attainable reality for all its citizens. Day was more than the sum of her charitable endeavors, thoughher corporal works of mercy, as the Church terms efforts at aiding the downtrodden. She was also a woman with an uncompromising political agenda.

Born on the eve of the Spanish-American War in the era of William McKinley, she lived to see the rise of Ronald Reagan and her countrys role as a world power with a nuclear arsenal of apocalyptic potential. Coming of age when the reach of the Catholic Church and its social acceptance in the United States was at its height, she lived to see American Catholics, postVatican II, turn from their faith in the 1970s in daunting numbers. Both were troubling developments to a woman who was for almost fifty years a great anomaly in American life: an orthodox Catholic and a political radical, a rebel who courted controversy, challenged three generations of young admirers, and willingly went to jail for her beliefs.

An impassioned critic of unfettered capitalism, US foreign policy, the nuclear arms race, and the debacle of the Vietnam War, Day was at the same time as skeptical of many of the tenets of modern liberalism as she was of political conservatism. She was outspoken as well about what she saw as the complacent, conflicted role of religion in our national life. In large numbers, Americans regularly tell pollsters that they see themselves as a religious people. Days concept of authentic belief, however, involved a good deal more than weekend church attendance and acceptance of an institutional creed.

The ideas Dorothy Day began to formulate in the early 1930s and exemplified to the time of her death in 1980 put her profoundly at odds with much of both secular and religious thought in the United States. She remains an outlier in that regard. The belief that material comfortand, in particular, wealthmight actually be dangerous, putting a distance between oneself and God and ones fundamental humanity, wasnt a notion Americans were, or are, comfortable with. She came to believe that the true objects of devotion in Western culturesecurity, affluence, national pride, an enthrallment to innovation and technologywere the sources of our undoing as a moral society, and she was impatient with anyone who made religion seem reassuring rather than demanding and transcendent. The New Testament called on all believers to fight racism, war, and poverty, or it meant nothing at all. Faith was less about solace than a call to action and disruption. Piety and conformity to social norms had little to do with each other.

None of these values was a part of Days upbringing. The child of a middle-class Republican family, nominally Protestant but essentially indifferent to religion and opposed to any kind of radicalism, Dorothy Day followed her own path from a young age. A precocious reader and budding intellectual, she dropped out of the University of Illinois after two years and found work in New York City as a reporter for various left-wing publications. The offices of the radical monthly The Masses, anarchist and socialist rallies at Union Square, the immigrant-filled streets of the Lower East Side, the avant-garde Provincetown Playhouse off Washington Squarethose were the real sources of her education.

Days romantic relationships with men such as Mike Gold, later a prominent American Communist and the author of Jews Without Money, and the playwright Eugene ONeill brought her into the orbit of a group of people who were creative, inspirational, politically radical, hard-drinking, and libidinous. That was Greenwich Village in the late 1910s, a much-mythologized site of intellectual ferment and unconventional mores. For four years, it was home. It was also a world with a dark underside: her passionate and physically abusive affair with a charismatic newsman, Lionel Moise, ended with a pregnancy and abortion in 1920, a decision she regretted all of her life that was followed by two suicide attempts during a period of deep depression.

Yet Dorothy Day was never a typical bohemian. Her closest friends, including the lapsed Catholic and spiritually tormented ONeill, knew of her clandestine visits to Catholic churches in the area. A night of carousing at the Hell Hole on Sixth Avenue, a dive of the shadiest kind, might be followed by a visit the next morning to St. Josephs Church a block northnot to repent any misdeed but to see if she could fathom what it was the silent worshippers in the pews were feeling, what it meant to pray and seek a communion with a higher power. It was a call, inexplicable at the time even to Day herself, that she had felt in adolescence and, when she was in her late twenties, finally led to her decision to be baptized as a Roman Catholic. Her reading of William James and G. K. Chesterton was instrumental in that process.

By the mid-1920s, Day had left behind her rowdy youth and had a child in a common-law marriage with a man whom she deeply loved but who had no patience with her spiritual longings. They parted. Her life changed, her Catholicism taking on a whole new meaning, when she met a French immigrant laborer and idiosyncratic intellectual, Peter Maurin. With Maurin, she scraped together the funds to begin publishing a newspaper (The Catholic Worker, a still extant monthly), a publication that eventually reached more than 100,000 readers. That was the eclectic forum Day had been looking for without even realizing it, a periodical that allowed her to travel the country to report personally on labor strikes and corporate abuses, to send her reporters out to document examples of home foreclosures and racial discrimination, and to offer a lacerating critique of Americans materialist values, all in a context that invoked Christs teachings, the example of St. Francis of Assisi, and papal encyclicals about social issues.

Within two years, as breadlines and Hoovervilles dotted the landscape of the city, she and Maurin opened a house of hospitality in one of New Yorks poorer neighborhoods (more than fifty would exist across the country by 1940). Unlike the settlement houses of an earlier era, a Catholic Worker house required the young people who lived and worked therelike Day and Maurin themselvesto share in the poverty of the homeless men and women they served. Soon after, Day and Maurin made an effort to open self-sustaining farming communities in rural areas that were intended to be places of spiritual retreat and refuge from the pressures of city life, linked also to Maurins special interest in fostering a green revolution, forty years before any attention to ecology and environmental issues was a part of the public discourse in the United States.

DOROTHY DAY: AN AMERICAN PARADOX

DOROTHY DAY: AN AMERICAN PARADOX